Updated

Nov 16, 2024, 05:30 AM

Published

Nov 16, 2024, 05:00 AM

SINGAPORE – The controversial use of the term “overlapping claims” in a maritime agreement signed recently between China and Indonesia could, some analysts say, boil down to diplomatic oversight or a misuse of words.

Regardless, this has mired Jakarta in an imbroglio, with potential repercussions for Asean nations.

And reactions from the international community have come fast and furious.

The phrase could undermine Indonesia’s ability to assert its sovereignty and territorial jurisdiction in the South China Sea, while also legitimising Beijing’s claims to parts of the waterway disputed by the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam.

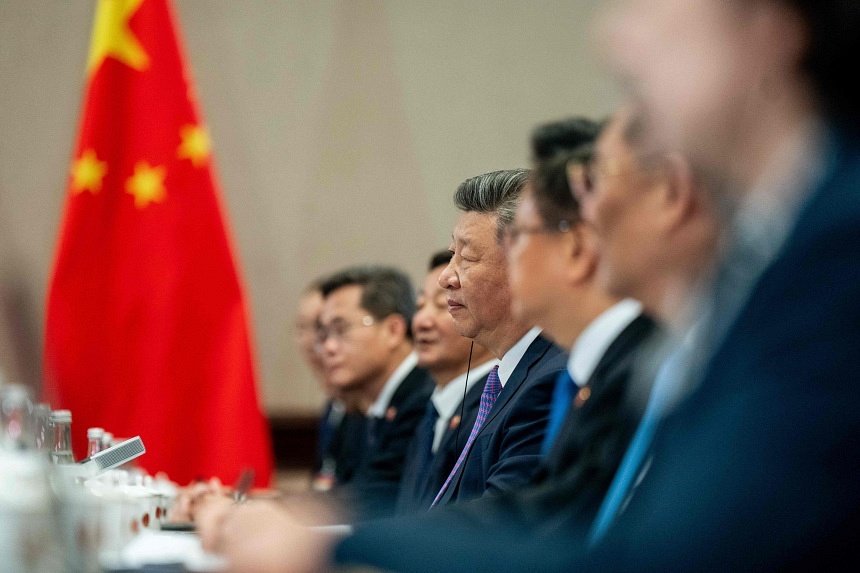

China and Indonesia announced on Nov 9 that they had reached common understanding “on joint development in areas of overlapping claims”. This was part of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed during newly minted President Prabowo Subianto’s visit to Beijing, his first official trip since taking office in October.

Jakarta had never formally acknowledged China’s competing claim before, noted Dr Abdul Rahman Yaacob, a research fellow at the Lowy Institute specialising in South-east Asia’s defence and security. So, if the joint statement’s phrasing was intended, it would constitute a major shift in its foreign policy.

However, Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry was quick to issue a response on Nov 10, maintaining its long-held position that it did not recognise China’s claims over the South China Sea.

“Indonesia reiterates its position that those (Chinese) claims have no international legal basis. The partnership does not impact sovereignty, sovereign rights or Indonesia’s jurisdiction in the North Natuna Sea,” it said.

China’s sweeping claim over the whole of the waterway is based on its nine-dash line map, which was ruled to have no basis under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) by a 2016 arbitral tribunal.

As Jakarta does not recognise Beijing’s nine-dash line, it considers itself a non-claimant in sovereignty disputes with China.

It has said that it has no overlapping jurisdiction with China, despite Beijing’s claims that encroach into Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone north of the Natuna islands, which extends 200 nautical miles from its coastline.

Indonesia in October said that it drove out a Chinese coast guard vessel from its North Natuna Sea at the southern edge of the South China Sea.

Dr Alexander Raymond Arifianto, a senior fellow and coordinator of Indonesia Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), postulated that the Nov 9 joint statement had been approved without considering the sensitivities or implications of such language.

“I think there is some inexperience and miscommunication that led to this,” he said.

Mr Sugiono, who is the deputy chairman of Mr Prabowo’s Gerindra party, took on the role of foreign minister in October. “Basically, both Mr Sugiono and Mr Prabowo are new to their jobs,” said Dr Alexander.

Intentional or not, the phrasing of the statement could be seen as Indonesia turning its back on the international rule of law, said maritime security expert Collin Koh of RSIS.

“This is clearly against national interests. One phrase has demolished Indonesia’s principled position on the South China Sea,” he said.

With the China-US strategic rivalry as its backdrop, the region has become a primary theatre for military and political muscle-flexing. Violent clashes have escalated between the Philippines and China in recent years.

“At the Asean level, some countries are looking at Indonesia as a big brother that can deal with China, especially in regard to the South China Sea dispute,” said Dr Rahman Yaacob, noting that some countries may even expect Mr Prabowo, a former military man, to take a harder stance on this issue.

He noted that the MOU has no legal obligations, but said it is important to watch for any follow-up policy or approaches to see if “overlapping claims” are further acknowledged. “That is something that other Asean claimants will be watching and worried about.”

Mr Prabowo, who was in the US after his trip to China, said on Nov 14 that he would “always safeguard our sovereignty” when asked about the issue. He told reporters that adding partnerships is better than conflicts.

The President has ambitious plans, including raising economic growth to 8 per cent from the current 5 per cent within his first term, and eradicating poverty in his country. He recently assembled a team of economic advisers headed by Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs Luhut Pandjaitan.

“He is a person in a rush... And he doesn’t want to be seen just as a strongman without economic credentials,” said RSIS’ Dr Koh, adding that Mr Prabowo will prioritise economic development to meet domestic expectations.

“So, he might be willing to relent on (the position) to China in exchange for economic incentives.”

When asked to clarify the use of the term “overlapping claims” during an interview at The Straits Times Asia Future Summit on Nov 12 in Singapore, Mr Luhut said that the President could be suggesting a joint study to see if a “South China Sea Council” based on the model of the Arctic Council could be used to reduce tensions in the area.

“But we have to comply also to the international law and Unclos, which is very important,” he said.

The Arctic Council is an intergovernmental forum dedicated to discussing aspects of the Arctic inhabitants, development, environment as well as scientific research. Membership is limited to the eight states with territories above the Arctic Circle, including Canada, Denmark, Russia and the US.

Much like in the South China Sea, there have been clashes between the coastal states in the Arctic. But the Arctic Council provides a cooperative framework, with nations committed to international law and arbitration tribunals, treaties and demilitarised zones, among others. The Arctic Council does not address military issues or questions of security.

Asean is currently engaged in negotiations with China over a Code of Conduct (COC) on the South China Sea. However, Dr Koh is of the perspective that the controversy will have little impact on the talks, which have been slow-moving since they began in 2018.

“I don’t see this as having a game-changing effect on the COC negotiations. Rather, this reflects the division in Asean and the divided interests that they pursue vis-a-vis China,” he said.

Dr Alexander said he hopes there will be some clarity on the issue soon, as the President completes a series of working visits to Lima, Peru and Brazil for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation and G-20 summits later in November.

“It is important for Indonesia to clarify the statement and tell other Asean nations that it is a bilateral deal and will not affect the grouping’s negotiations over the South China Sea.”

By The Straits Times | Created at 2024-11-15 21:43:35 | Updated at 2024-11-16 00:18:36

3 hours ago

By The Straits Times | Created at 2024-11-15 21:43:35 | Updated at 2024-11-16 00:18:36

3 hours ago