This is the second new book that David Graeber, the anthropologist and anarchist, has published since his death aged fifty-nine in late 2020, and that his thoughts continue to surprise, challenge and confuse us says a great deal about the depth of his intellectual creativity. The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World is an entertaining smorgasbord of his ideas, drawn from various essay collections and articles and interviews with him, edited by his wife and co-author, Nika Dubrovsky.

Some of the entries are cautious and academic while others are more journalistic and polemical. The virally successful “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs” (2013) – which helped to bring his work to popular attention and was later expanded into a book, Bullshit Jobs (2018) – encompasses both styles. Most of the time, it is hard to draw a clear line between Graeber’s scholarly insights and his political activism. Perhaps, though, that is how he thought it ought to be. As Dubrovsky writes in her introduction to the book, Graeber was an “anarchist-scholar”, the two parts of his life fused in a way that could not be easily disentangled.

“Anthropologists”, Graeber writes in one essay, “are drawn to areas of density.” This book reflects that observation: it is dense, disorientating in its richness and range, moving quickly over vast areas of terrain. There are passing references to medieval Iceland, pirate ships and Native American confederations; quick asides about Swazi Ncwala ritual and Zande witchcraft; fleeting discussions of Algonkian refusals to adopt Inuit kayaks and Inuit refusals to adopt Algonkian snowshoes. Nods are made to Herderian and Hegelian processes, Marxian and Maussian tradition. We confront unexplained terms like “schizmogenesis” (which refers to the process by which social divisions form and is derived from cybernetic systems theory).

If there is a common theme, it is the author’s relish for attacking conventional wisdom. Thus, we learn that there never was a West; that anarchism and democracy are the same; that a state can never be democratic. (A leading figure in the Occupy movement, Graeber helped to coin the slogan “We are the 99%”.) The author has little respect for the traditional boundaries between scholarly disciplines and he is happy to traverse them himself: he believes that philosophers have got consciousness wrong, that political scientists have got anarchy wrong, that ethologists have got animal play wrong. This contrarian streak carries him to dangerous places. “It is unclear”, he writes in an essay on hatred, “if Hitler personally hated the Jews (“There are indeed many indications they were emotionally incapably of any such deep feelings”). At one point, Graeber recalls a youthful interest in “Robert Graves and his ideas on poetry” as well as “a fascination with Mayan hieroglyphics”. He always was an intellectual magpie, drawn throughout his life to a vast spread of different shiny ideas. But at times this enthusiasm spreads him too thin. And this is nowhere more apparent than in his take on economics.

Historians, argues Graeber, “obviously do the most detailed, empirically informed work”, whereas economists “go all the way the other way. It’s all models. They don’t really care what’s there”. This might have been a reasonable picture of the field forty years ago, but it does not reflect the field today. Over the past few decades, economics has undergone an “empirical turn” and the proportion of empirical papers published in leading journals has soared. Economists have talked about the “death of theory” for some time. And any young aspiring economist knows they have to master these data skills if they want to get on in the field.

Then there are Graeber’s complaints about what economists focus on. “It is beginning to look like a science designed to solve problems that no longer exist”, he wrote in an essay of 2019, and “a good example is the obsession with inflation.” This statement already feels woefully dated. This is, after all, a year in which, for the first time since records began, all governing parties in developed countries lost vote share in national elections – and the main reason is inflation. The rising cost of living felled Rishi Sunak, defenestrated Emmanuel Macron and propelled Donald Trump back to power. If anything, economists have spent too little time in recent years studying inflation.

This mischaracterization of economics is a good example of why it is so risky to blend activism and academia. Graeber, with his scholarly hat on, would surely recognize the richness of the field – the “density” – and the baffling variety of tools used by economists, the kaleidoscopic nature of their preoccupations, the ways those have changed over time and vary from place to place, why some are useful and others foolish. But he does not. Instead he reduces economics to a cartoon stylization, exhibiting the kind of failure to respect heterogeneity that he himself laments elsewhere (see, for example, the opening essay, in which he decries Samuel Huntingdon’s reductive ideas of “the West”).

What strikes the reader throughout is Graeber’s faith in the benevolence of human beings. This optimism underpins his anarchism: a belief that people are fundamentally good and that it is our man-made institutions – the state, the market – that corrupt them. “Anarchists”, Graeber writes, “believe that for the most part it is power itself, and the effects of power, that make people stupid and irresponsible.” Perhaps that is the real difference between him and my own tribe: economists tend to take human beings as they are in the world, self-interested and partial, and try to build institutions to channel those instincts towards the greater good; Graeber, by contrast, takes human beings as he wants them to be, selfless and impartial, and wants to dismantle those very same institutions that he believes get in their way.

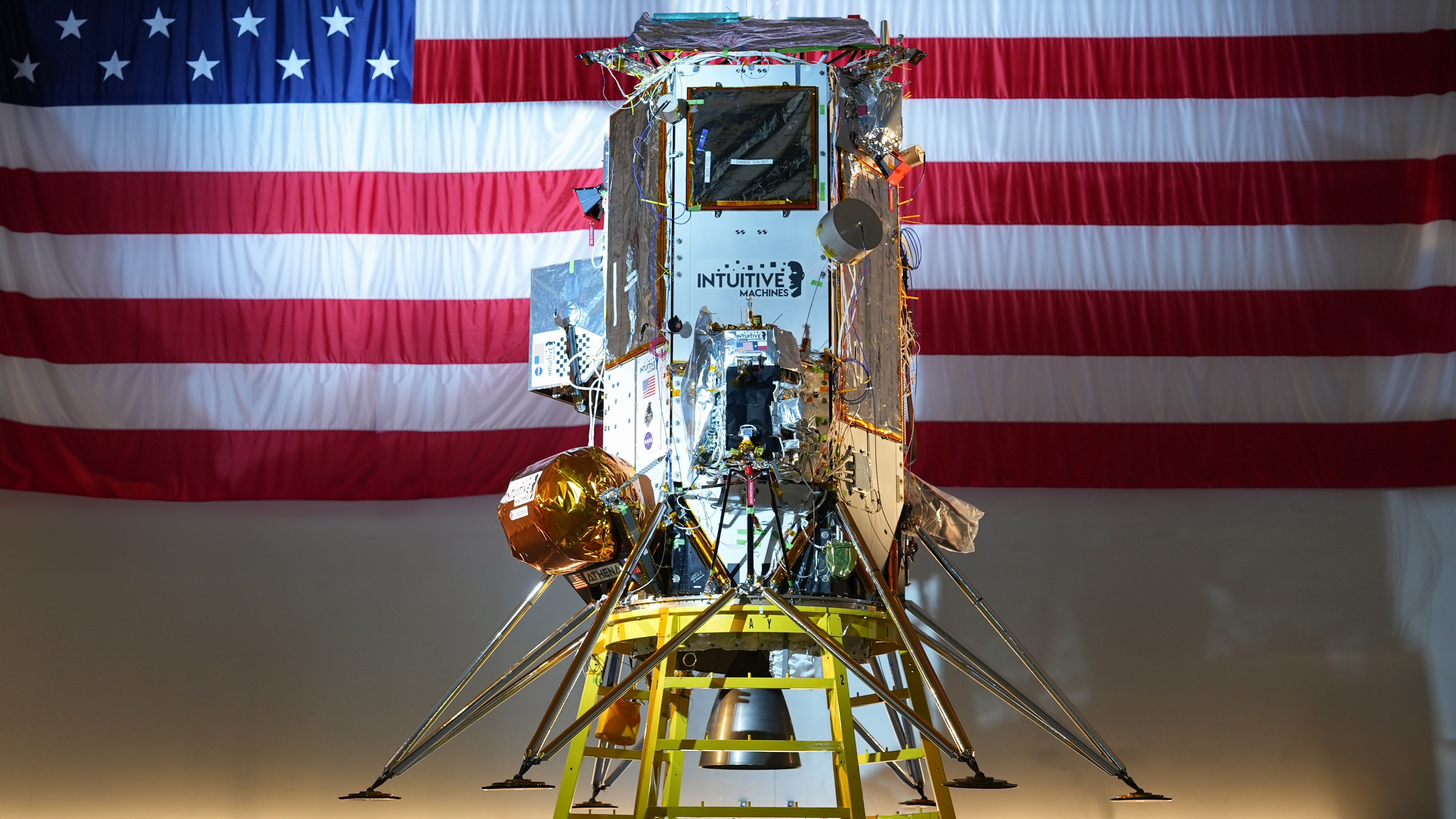

But, given Graeber’s optimism about human nature, he is strangely pessimistic about human invention. It seems odd to have so much faith in one dimension of human beings (their capacity for co-operation and prosociality) and so little in another. In 2014, in an interview with the economist Thomas Piketty, Graeber claimed that “signs of a slowing down of the capitalist system are visible. So far as technology is concerned, we no longer have the sense, as we did in the 1960s and 1970s, that we are about to see great innovations”. Again, the timing of this claim was unfortunate. As he was speaking, a “deep learning” revolution was already underway in the world of artificial intelligence. Indeed, in January of that year, the AI company DeepMind had been bought by Google. And now, a decade later, we are saturated with “great innovations”. Every day, it seems, we hear stories of AI taking on tasks that, until very recently, it was assumed only human beings could do: making medical diagnoses and composing amusing jokes, drafting legal arguments and designing beautiful buildings, writing lines of code and forming apparently meaningful relationships. In 2024, Demis Hassabis, the founder of DeepMind, won the Nobel prize in Chemistry for solving the “protein-folding problem”. Contrary to Graeber’s claim, this is perhaps the most significant moment of technological progress in human history.

Again, I fear that Graeber’s dislike of capitalism, rooted in his activism, clouds his scholarly judgement. He is not alone. This is a more general problem in activist research, seen among those who care about climate change but are unwilling to admit that capitalism – with the extraordinarily powerful incentives it creates – is likely the only tool we have to change the direction of technological progress, away from dirty technologies towards cleaner ones; or seen among those who care about poverty but are unwilling to accept that capitalism – with its record of lifting more than one billion people out of extreme poverty since 1990 – might be the only mechanism capable of completing the job.

The title of Graeber’s new book is drawn from a line he wrote in an earlier one, The Utopia of Rules (2015): “the ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make, and could just as easily make differently”. The spirit of that claim sounded familiar to me. Eventually, I remembered where I had heard it – from Steve Jobs. “Life”, said Jobs in an interview,

can be much broader once you discover one simple fact, and that is everything around you that you call “life” was made up by people that were no smarter than you, and you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use … shake off this erroneous notion that life is there and you’re just going to live in it.

It is an interesting realization, to see opposing sides of the political spectrum – anarchism and free-market capitalism – bending back on one another to meet in unexpected agreement, to see the shared sense that our prevailing institutions are letting us down in profound ways and that we must be more imaginative and bold about what might take their place. That at least is a philosophy one can get on board with.

Daniel Susskind is a Research Professor in Economics at King’s College London and a Senior Research Associate at the Institute for Ethics in AI at the University of Oxford. His most recent book is Growth: A reckoning, 2024

The post Anarchy in the UK appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:39:17

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:39:17

1 week ago