For many reasons, the Falklands/Malvinas War stands out among post-war conflicts, with Argentina’s surprise attack on the tiny British territory, nearly 8,000 miles from the United Kingdom, precipitating a fierce campaign fought on land, at sea, and in the air. The conflict also saw some notable innovations, including the rapid introduction of new weapons and tactics. Surely one of the most unusual, however, was the Argentine Air Force’s effort to provide countermeasures to better protect its aircraft.

The bizarre story involves infrared flares, radar-defeating chaff… and a pasta machine.

One of two AIM-9L Sidewinders fired by a British Royal Navy Sea Harrier at a pair of Argentine IAI Dagger fighters on May 24, 1982. The missiles destroyed them both. via Rowland White

One of two AIM-9L Sidewinders fired by a British Royal Navy Sea Harrier at a pair of Argentine IAI Dagger fighters on May 24, 1982. The missiles destroyed them both. via Rowland White Years after the conflict, a U.S. Air Force pilot asked Pablo Carballo, a Malvinas veteran A-4B Skyhawk pilot, what Argentine airmen felt when the radar warning receiver on their aircraft was activated, alerting them to a possible missile inbound.

“Nothing,” Carballo said.

Amazed, the American pilot replied, “How brave!”

“No, you misunderstood me,” Carballo continued. “We didn’t really feel anything because our planes had no radar warning receiver.”

As Capt. Carballo, who was a squadron leader and operations officer of Fighter Group 5, explains in this anecdote that the Argentine Air Force did not have radar-warning equipment for its fighter-bombers in the Falklands War. As far as self-protection systems such as chaff and flares were concerned, the few examples that were introduced by the Argentines during the conflict were the result of ingenuity. Few of them ended well.

As of 1982, the Argentine Air Force (locally, the Fuerza Aérea Argentina, FAA) had no electronic warfare or countermeasures systems in its aircraft. Chronic budgetary problems, as well as the scarcity of guided weaponry in neighboring countries that could pose a threat to Argentina, meant that the purchase of these systems had been ruled out. The Argentine Air Force’s A-4B and C Skyhawk fighter-bombers, Dassault Mirage III and IAI Dagger fighters, and English Electric Canberra bombers, therefore, flew “unprotected.”

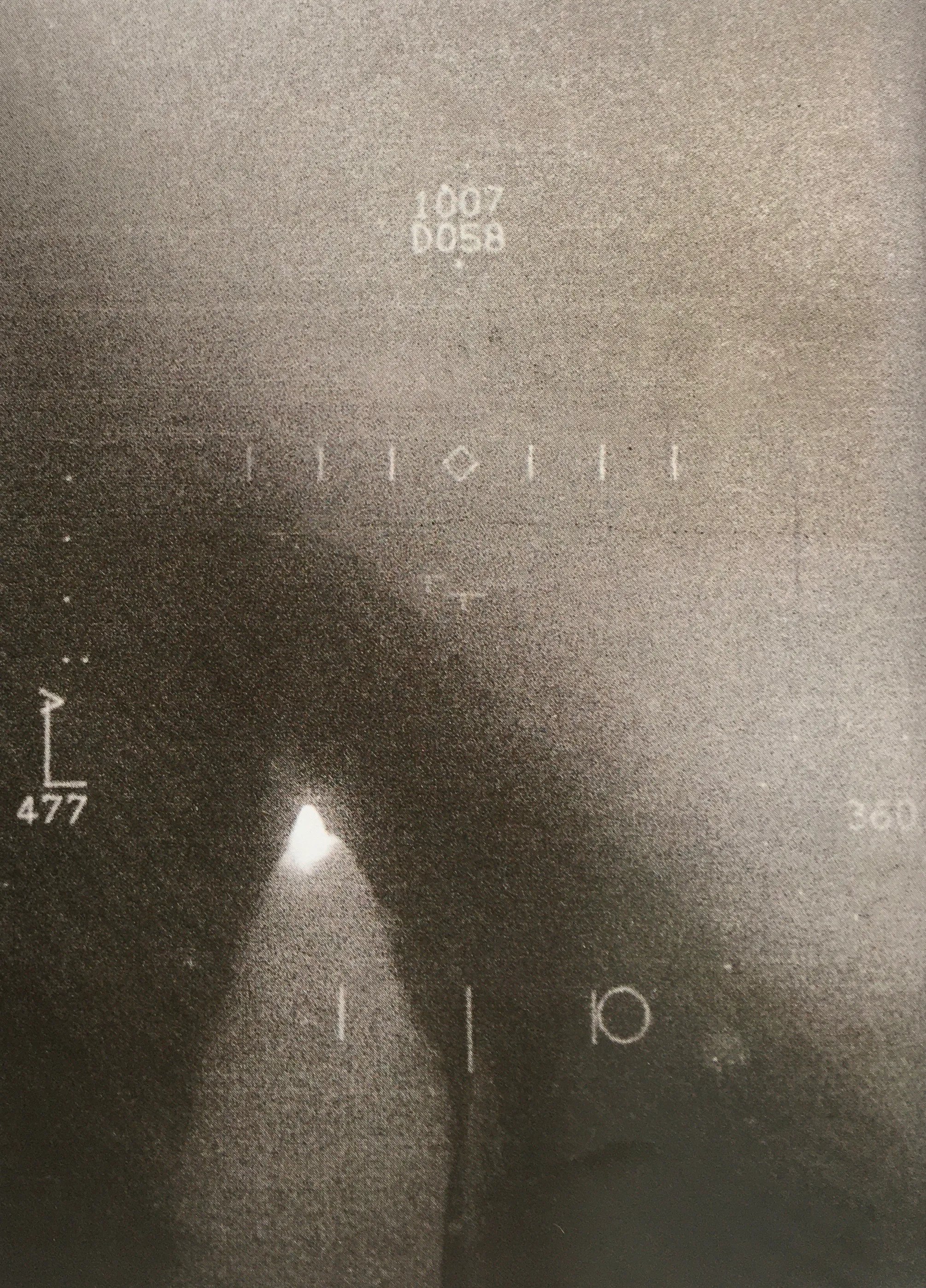

A formation of Argentine Air Force A-4 Skyhawk fighter-bombers around the time of the Falklands War. Photo By: Fireshot/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Fireshot

A formation of Argentine Air Force A-4 Skyhawk fighter-bombers around the time of the Falklands War. Photo By: Fireshot/Universal Images Group via Getty Images FireshotIn the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Argentine Air Force had looked at some upgrade programs that would have included self-protection systems. For example, in November 1980, France’s Thomson-CSF submitted a proposal to integrate Sherloc warning systems, as well as Remora and Caiman countermeasures pods on the FAA’s Mirage IIIEA. In 1981, there were negotiations with Elta of Israel to fit a Boeing 707 with electronic warfare systems (which ended up as a signals intelligence platform) and to install self-protection systems on the fighter and bomber fleets. However, when the Falklands War broke out in April 1982, none of these systems had been installed.

An Argentine Air Force Mirage IIIEA. Dassault Aviation

An Argentine Air Force Mirage IIIEA. Dassault Aviation Most of the FAA units were taken by surprise by the landing of Argentine troops in the Falklands. It was only after the assault and the British announcements that a task force would head south to retake the islands that work began on various projects that would give the FAA’s aircraft a better chance of survival against an enemy with technology and resources far superior to those available anywhere in South America.

Argentine Marines of the 2nd Marine Battalion outside Government House following the capture and occupation of Port Stanley in the Falklands on April 2, 1982. Crown Copyright

Argentine Marines of the 2nd Marine Battalion outside Government House following the capture and occupation of Port Stanley in the Falklands on April 2, 1982. Crown Copyright From the outset, it was considered that the main threats to Argentine aircraft would be British Royal Navy Sea Harrier aircraft armed with AIM-9 Sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missiles, as well as ship-launched missiles, mainly radar-guided ones, such as the ramjet-powered Sea Dart. To distract the former, flares were to be launched; for the latter, chaff would be used.

A Sea Harrier on the amphibious assault ship HMS Fearless during the Falklands War 1982. The jet had been unable to land at the damaged Sheathbill airstrip on the islands. Photo by Terence Laheney/Getty Images Terence Laheney

A Sea Harrier on the amphibious assault ship HMS Fearless during the Falklands War 1982. The jet had been unable to land at the damaged Sheathbill airstrip on the islands. Photo by Terence Laheney/Getty Images Terence LaheneyA number of projects were launched in parallel without full coordination. These efforts involved both the Institute of Scientific and Technical Research of the Armed Forces (CITEFA), the main body responsible for defense research and development. Also involved were various FAA units and civilian institutions.

The initial problem was how to manufacture chaff. Only later would thought be given on how aircraft would actually deploy it.

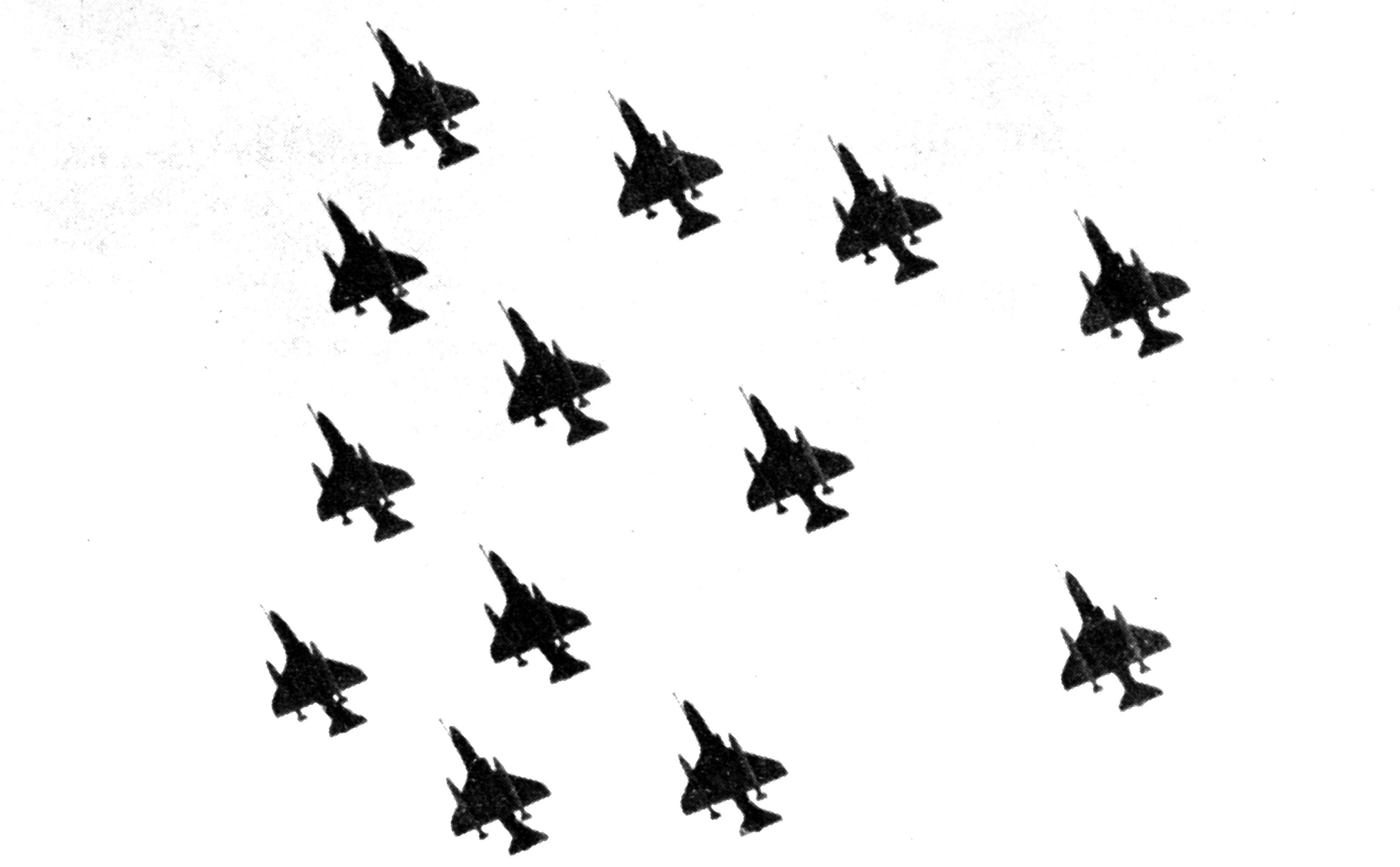

Chaff has been used since World War II, where it was known by Allied forces as Window and by the Germans as Düppel. Essentially, it consists of small, thin strips of aluminum (or similar) that appear as a cluster of targets on an enemy radar screen or otherwise saturate it with multiple returns.

A Royal Air Force Lancaster releases bundles of Window over the target during a daylight raid on Duisburg, Germany, in October 1944. Right: The same Lancaster drops the main part of its load, comprising a 4,000-pound high-explosive bomb and 108 30-pound incendiaries. Crown Copyright

A Royal Air Force Lancaster releases bundles of Window over the target during a daylight raid on Duisburg, Germany, in October 1944. Right: The same Lancaster drops the main part of its load, comprising a 4,000-pound high-explosive bomb and 108 30-pound incendiaries. Crown Copyright According to an intelligence report from the Southern Air Force (FAS), the FAA’s primary combat command on the mainland, officers at least knew the theory behind chaff and recognized that “before initiating chaff launch operations, accurate data on frequencies, pulse widths and beam widths of enemy radars to be disrupted must be known.”

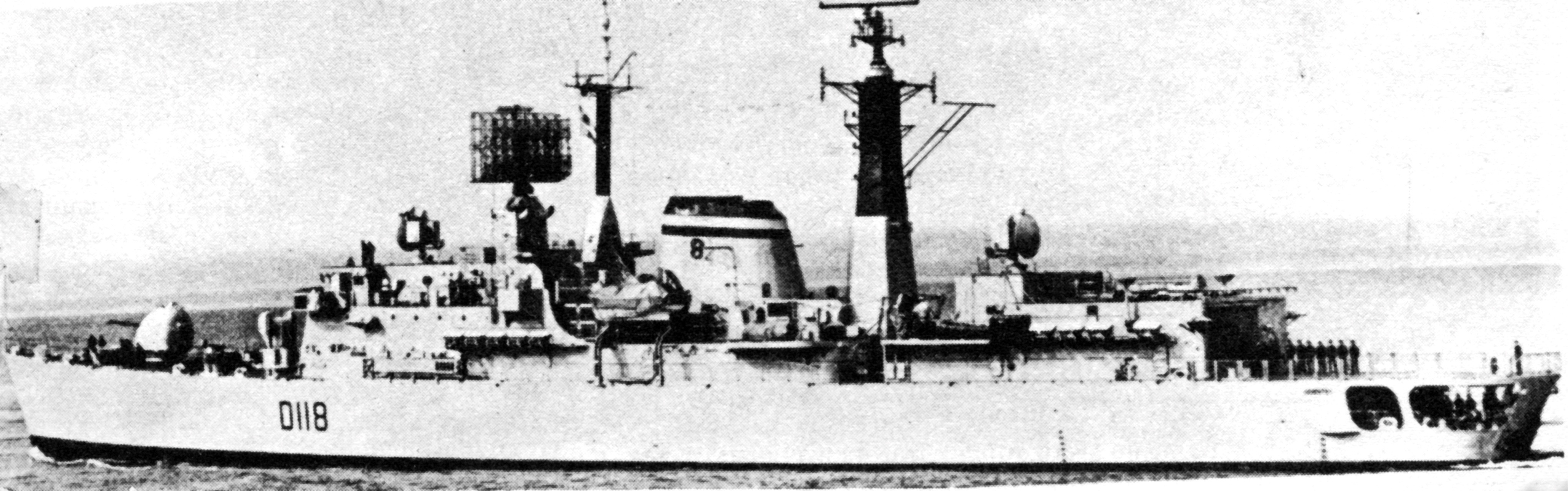

This was not a problem since the Argentine Navy operated two modern British-made Type 42 destroyers (ARA Hércules and ARA Santísima Trinidad), essentially sister vessels to the Royal Navy’s main air defense warships, the Sheffield class. Therefore, the characteristics of the British Type 965 radars (air surveillance) and Type 909 (Sea Dart fire control) were well known. The capabilities of certain other British naval and air radars were also understood since they had also been offered to the Argentine military in the past.

The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was sunk by Argentine Air Force A-4 Skyhawks on May 25, 1982. Photo By: Fireshot/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Fireshot

The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was sunk by Argentine Air Force A-4 Skyhawks on May 25, 1982. Photo By: Fireshot/Universal Images Group via Getty Images FireshotThe chaff was to be fabricated using this data.

The same FAS report notes that “considering that chaff is resonant over a very wide band, no excessive effort is required to cut it accurately. Chaff cut off at a length approximately equal to 0.475 times the wavelength of the radar to be disrupted will normally be effective.”

As of early May 1982, 140 kilograms (309 pounds) of chaff, cut to saturate radars in the 2-18 GHz frequency, was available at the military air base (BAM) Comodoro Rivadavia, in the province of Chubut in southern Argentina. Other chaff shipments were also due to arrive there.

While it’s not clear where the entire stock came from, at least some of it was made by schoolchildren in a distant Argentine province, and some of it was fabricated using a pasta machine.

In 1982, Maj. Fernando Rezoagli was head of the technical squadron deployed with the Canberra bombers of Bombardment Group 2 at BAM Trelew, also in Chubut, when he was ordered to return home to faraway Paraná, Entre Ríos, in Argentina’s northeastern Mesopotamia region. His mission: to make chaff.

His house in Paraná was close to the II Brigada Aérea hangars.

“I removed a roll of aluminum from the depot, which was used to wrap the exhaust nozzles of the Canberra’s engines and dissipate heat. I phoned my oldest son, who was 15 years old and in high school, and told him to bring three or four classmates home and that each should bring a pair of scissors. And I asked him to tell his younger brother, who was 13, to do the same thing.”

Although they cut chaff all night, it was not enough.

Discussing the problem, a non-commissioned officer “told us that he had an idea that could be useful… it involved using a machine to make noodles, taking advantage of the fact that the width of the noodles was similar to that of the chaff. The next day, he showed up at the technical group with an industrial machine that he had borrowed from a pasta factory called Napoli. And we started to work the handle 24 hours a day, for about a week”.

In the small museum of the II Air Brigade, there is the pasta machine that was used to make chaff. In front of it is the system installed in the Canberras, with the canisters in which the flares and chaff were placed. via author

In the small museum of the II Air Brigade, there is the pasta machine that was used to make chaff. In front of it is the system installed in the Canberras, with the canisters in which the flares and chaff were placed. via author Once the chaff arrived at BAM Comodoro Rivadavia, it was tested on the aircraft operating from there, the Mirage IIIEA fighters and C-130 Hercules transports.

In the case of the Mirage, it was decided to make, by hand, cartridges of about 1.5 inches in diameter “wrapped in toilet paper, kept in the wrapper with adhesive tape.” They would be placed inside the airbrake and fixed to it with more adhesive tape.

As for the C-130s, the chaff “would be thrown from the door in a bag tied with a string about three meters [10 feet] long and in a trajectory perpendicular to the main axis of the search radar lobe, trying to form a curtain.”

The chaff was separated by size. Chaff of 40, 47.5, 57, 71, and 110 millimeters was used for the C-130 bags, and chaff of 16, 37/40, and 85 millimeters for the fighters. These sizes were tailored for the various search and targeting radars based on available intelligence.

Chaff installed in the airbrakes was also used by the Dagger fighters deployed at BAM San Julian, in Argentina’s Patagonian region, and BAM Rio Grande, in Tierra del Fuego province, both of these being in the southern part of the country. The problem, however, was the scarcity of the chaff and the fact that pilots would open the airbrakes to decelerate and maintain formation, thus losing the one opportunity they had to use it in combat. The chaff was never used by the C-130s.

An Argentine Air Force IAI Dagger passes low over the British landing ship RFA Sir Bedivere in San Carlos Water, Falklands, on May 24, 1982. Photo by Peter Holdgate/ Crown Copyright. Imperial War Museums via Getty Images digitised by Ted Dearberg (IWM)

An Argentine Air Force IAI Dagger passes low over the British landing ship RFA Sir Bedivere in San Carlos Water, Falklands, on May 24, 1982. Photo by Peter Holdgate/ Crown Copyright. Imperial War Museums via Getty Images digitised by Ted Dearberg (IWM)A more sophisticated system was a chaff launcher, designed by CITEFA, of which 10 units were built, initially for the A-4 fighter-bombers.

The completed system was tested on June 2, 1982, on an A-4C operating from BAM San Julian, with test launches made from between 100 and 15,000 feet. The system allowed two launches every five seconds and salvo launches of six chaff rounds every four seconds. The target to be jammed was the base’s Skyguard fire-control radar, which was around three to four miles away. However, no positive results were obtained.

Other unsuccessful projects included chaff launched by 2.75-inch Folding-Fin Aerial Rockets (FFAR), or from Shafrir 2 air-to-air missiles, or semi-automatic systems proposed by private companies.

In the end, the only countermeasures system that appears to have been at least partially successful during the 1982 conflict was the one installed on the Canberra unit supported by Maj. Rezoagli. The system launched chaff (cut by hand or the pasta machine) and, simultaneously, flares.

It was the brainchild of the chief of the technical group supporting the Canberras back in Paraná. The system consisted of seven horizontal launchers, parallel to each other, on the tail of the aircraft. In each of the launchers was an aircraft engine starter cartridge (already used), which contained a flare and some chaff. Finally, a cap sealed the cartridge.

Seen here unloaded, the chaff/flare launching system was installed near the tail of the Canberra. via author

Seen here unloaded, the chaff/flare launching system was installed near the tail of the Canberra. via author The flare (which was also hastily manufactured) was made of gunpowder that burned at 500° Celsius (932° Fahrenheit) for 15 seconds and floated in the air under a small parachute.

A control board in front of the navigator contained a button that launched each of the cartridges containing the flare and the chaff.

Prior to installation, the system was tested from a helicopter flying at 200 meters (656 feet), with the flare slowly descending under the parachute and a large cloud of metallic strips floating around it. By May 1, 1982, it was operational.

That same day, at 4:20 p.m. local time, three Canberra Mk 62s, complying with Fragmentary Order 1117, took off from their base in Trelew. This was RIFLE flight, and it was tasked with dropping bombs on British landing craft in the islands. The Canberras were all equipped with the improvised chaff/flare systems.

Capt. Eduardo García Puebla was the pilot of RIFLE 3, and Lt. Jorge Segat was his navigator.

Capt. García Puebla recounts the story, starting when they were 300 kilometers (186 miles) from the target.

“At that moment, something indescribable impelled me to look to the right, forcing the natural position of the seat. I don’t know what mechanism or sense alerted me, but I did. From a cloud, a small whitish flash appeared with astonishing speed. It was heading parallel to my course, towards No. 1 [callsign Pajaro]. When that image was engraved in my retina, I was already shouting with all my strength: ‘Pajaro, break, a missile. Break.’ Simultaneously, I violently activated the throttles to their maximum rate, and the control yoke and pedal to the left and back. ‘Jorge, launch flares and chaff, every 15 seconds!’”

The AIM-9L Sidewinder locked onto the hot engine nozzle of the No. 2 Canberra, which had failed to launch flares, shooting it down.

Canberra serial B-108 was the example shot down on June 14. Here, it is shown with the armament it could carry, during an exhibition in 1978. The largest bombs are Mk 17s of 1,000 pounds. via author

Canberra serial B-108 was the example shot down on June 14. Here, it is shown with the armament it could carry, during an exhibition in 1978. The largest bombs are Mk 17s of 1,000 pounds. via author Garcia Puebla and Segat also managed to avoid two other AIM-9L missiles and were able to return to base.

The first missile fired shot down the Canberra of pilot Lt. Eduardo Raul de Ibanez and navigator 1st Lt. Mario Gonzalez. It was launched by the Sea Harrier flown by Lt. William Alan Curtis of 801 Naval Air Squadron. Lt. Cdr. Mike Broadwater, in another Sea Harrier, had launched the two missiles that did not hit. You can read all about the success of the AIM-9L in the Falklands in this previous TWZ article.

An AIM-9L Sidewinder missile on an 800 Naval Air Squadron Sea Harrier during the conflict. Photo by Terence Laheney/Getty Images Terence Laheney

An AIM-9L Sidewinder missile on an 800 Naval Air Squadron Sea Harrier during the conflict. Photo by Terence Laheney/Getty Images Terence LaheneyThe other Canberra lost in the conflict, crewed by Captains Roberto Pastrán and Fernando Casado, was shot down in the early morning of June 14. It also failed to launch chaff and flares and was hit by a Sea Dart missile from the destroyer HMS Cardiff.

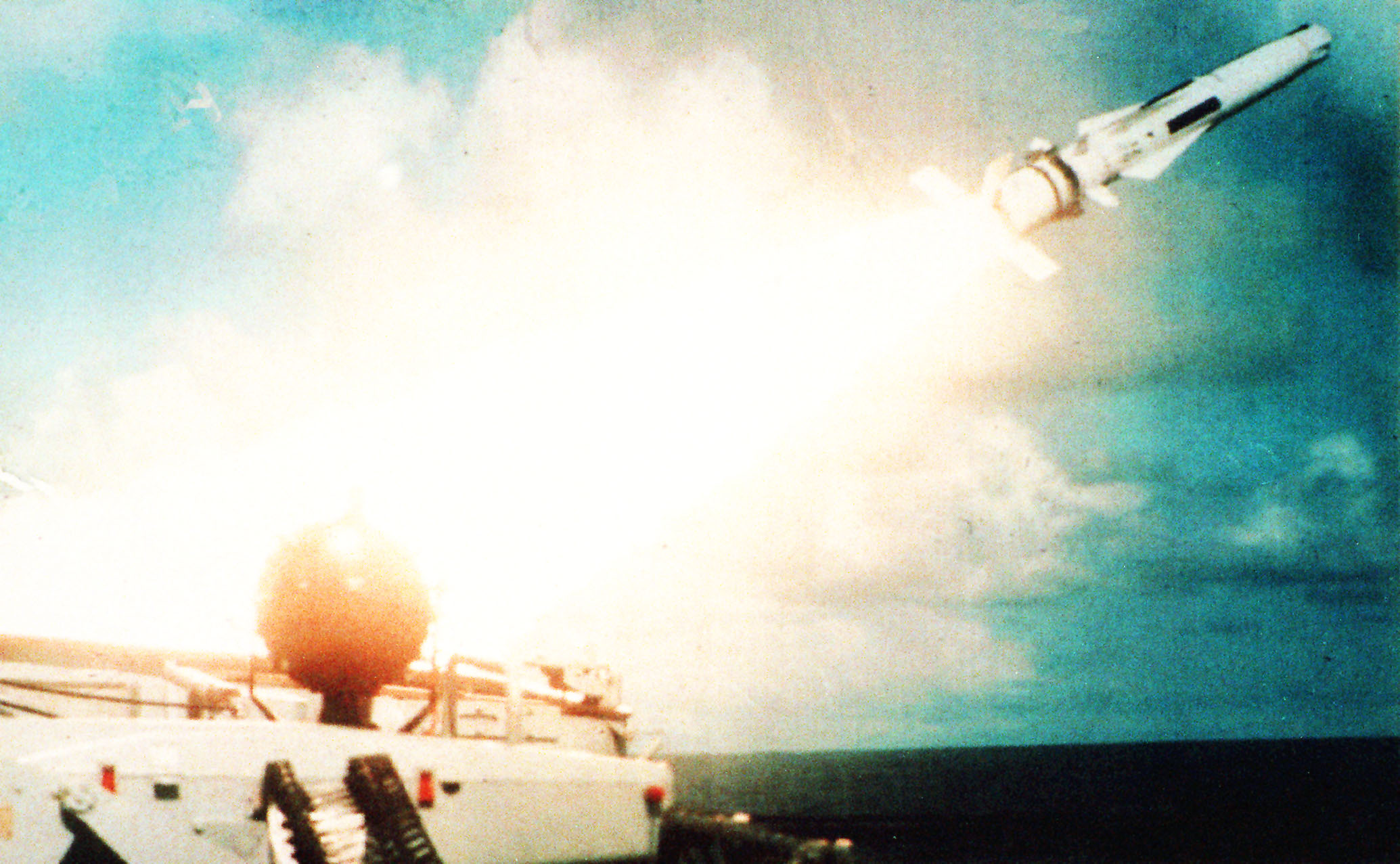

Launch of a Sea Dart missile. Photo by PA Images via Getty Images PA Images

Launch of a Sea Dart missile. Photo by PA Images via Getty Images PA ImagesNevertheless, the use of chaff/flares was customary for the aircraft of Bombardment Group 2 during the war.

It’s difficult to determine their effectiveness, however, as the post-conflict reconstruction of events (conducted in the United Kingdom) does not indicate that these systems deflected any missiles heading toward a Canberra bomber. On the other hand, it shouldn’t be ruled out. Quite possibly, García Puebla and Segat owe their lives to this system. Perhaps other Canberra crew members do, too.

Whatever the truth, the history of the Argentine Air Force’s chaff and flare systems during the 1982 conflict is surely a unique one, and not just because of the involvement of a group of school kids and a pasta machine.

Contact the editor: [email protected]

Mariano Sciaroni holds a master’s degree in Strategy and Geopolitics as well as a postgraduate diploma in Contemporary Military History, both earned at the Argentine Army’s Military Academy. Sciaroni has published five books and numerous articles on military and naval history. He is also an active member of the Argentine Institute of Military History and serves as a sub-lieutenant in the Argentine Army Reserve (Army Aviation Reserve Squadron). You can find out more about his books here.

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-14 19:11:25 | Updated at 2025-03-14 21:51:48

2 hours ago

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-14 19:11:25 | Updated at 2025-03-14 21:51:48

2 hours ago