For citation, please use:

Zuenko, I.Yu., 2024. Between Cooperation and Alarmism: Problems of Common History Interpretation in Russia and China. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(4), pp. 155–170. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-4-155-170

The Russia-China strategic partnership, one of the fundamental components of the new world order, is in many ways unique. It is evolving absent a military-political alliance and is thereby a “great-power relationship of a new type” (新型大国关系) (Wang, 2023). It is developing not on the basis of cultural and civilizational similarity, but in spite of cultural and civilizational differences. And it is based on mutual concessions, most prominently when the territorial dispute was settled in the early 2010s.[1] This removed the last remaining obstacle to the development of relations, which “have reached the highest level in their history” (Putin, 2023).

However, despite the rapid development of pragmatic and mutually-beneficial cooperation over the past four decades, spurred by mutual benefit and changes in the global geopolitical situation, proper study of the two states’ common history has lagged behind political expediency. This history is full of episodes that are still interpreted from nationalist-patriotic perspectives. Such divergences in understanding could potentially overshadow or nullify the development of bilateral relations.

How serious are these differences? How do divergent understandings of common history translate into concrete actions on both sides, primarily at the local level? How do government officials, businesspeople, social activists, and experts maneuver between cooperation and alarmism in Russian-Chinese interaction? This article is intended to answer these questions.

This paper does not seek to produce the only correct interpretation of history or to impose it on foreign partners. (Although, being a Russian researcher, the author naturally adheres to the interpretations adopted in Russian historical science). It is much more important to identify the problems that objectively exist in the perception of Russian-Chinese history. This will allow each side to “hear” its partner, understand the partner’s concerns over particular historical episodes, avoid misinterpreting the partner’s words or actions, and avoid unintentionally offending the partner (as has already repeatedly happened (see Zuenko, 2020)).

The article consists of two sections. The first analyzes the sore points in Russian-Chinese history. The second demonstrates how complexes and phobias, stemming from insufficient attention to past episodes, manifest themselves today in the context of growing Russian and Chinese nationalism. The conclusions at the end of the paper are not final, but rather provide the basis for further research within the “Historical-Grievance Narratives in the Official Discourse and Public Policy of Northeast Asian Countries” project. They also serve as an invitation to further discussion.

Historical Retrospective: Disputed Episodes in Russian-Chinese Relations

The history of Russian-Chinese relations is generally cyclical, with periods of hostility followed by periods of cooperation and friendship. The two countries have clashed several times: Cossack-Manchu skirmishes in the 1650s, the sieges of Albazin in 1685 and 1686-1687, the siege of Selenga in 1688 by the Mongols and the Qing Empire’s tributaries, a Chinese attack on Blagoveshchensk during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, Russia’s participation in the Eight-Nation Alliance to suppress that rebellion in 1900-1901, a conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway in 1929, and clashes on Damansky Island and near Lake Zhalanashkol in 1969.

There have been no full-scale wars between Russia and China. The local, small-scale scuffles were of only secondary importance to both parties,[2] and the disputes underlying them were generally absent from socio-political discussion, known only to narrow circles of specialists. Nevertheless, these controversies were never resolved, and they continue to provide fertile ground for anti-Russian and anti-Chinese sentiment.

Why did Russia and China fight each other, and what do their potential differences at this point consist of? There are three key factors driving the contradictory development of their relations:

Firstly, territorial delimitation between the countries was carried out after their mutual expansion into the lands populated by the Manchu-Tungusic peoples, which had previously not been part of either Russia or China. The Treaty of Nerchinsk, concluded in 1689 with the Manchus, drew a rough border between the two countries. Their modern border was established by the Treaty of Aigun (1858), the Treaty of Beijing (1860), and the Treaty of Ili (1881), which were signed when Russia was at its peak and Qing China, by contrast, was in decline.

Secondly, modern China is a multiethnic state, in which the core ethnicity (Chinese, the Han (汉族), considers all the lands of China’s ethnic minorities to be historically its own. The Manchus—a Manchu-Tungusic people who established the Qing Empire over China in the 17th century but eventually lost their own statehood after Xinghai Revolution (1911)[3]—were declared by the Republic of China to be one of the peoples of the “Chinese nation” (zhonghua minzu; 中华民族). The historical achievements of the Manchu were thus “appropriated” by China. Both China and the de facto government of Taiwan now consider the lands once controlled by the Manchus to be their own historical territories.

Thirdly, both countries used communist ideas in pursuing catch-up modernization at the beginning of the 20th century. Both the USSR and the PRC were simultaneously imperial successor-states and new international actors. Chinese historiography clearly distinguishes between “tsarist Russia” (Sha E; 沙俄), an expansionist colonial power, and modern Russia, exempted from criticism. However, in a sense, this permitted the preservation of a negative attitude towards China’s northern neighbor, albeit in the form of “tsarist Russia.”

The Comintern’s introduction of the communist movement to China, and the subsequent split of the two “fraternal parties” still cloud Chinese perceptions of Russia. A number of events that are barely known in Russia—the Soviet Union’s 1958 proposal to build a radar station in China to track submarines in the Pacific in the interests of Moscow, refusal to help Beijing build its own fleet of nuclear submarines, and the recall of Soviet specialists from China in 1960—created a long-lived perception of Russia as an untrustworthy “hegemon” and “social imperialist.”

It should be noted that the “Chinese world” is not limited to just China proper.

Many people in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and Chinese political emigrants living in the West view Russia not only as a colonial power that “seized a significant part of Chinese territory” but also as the source of the communist ideology that “destroyed” classical Chinese civilization on the mainland.[4]

While Sino-Soviet relations had been ideologized and dependent on the personal ambitions of communist leaders, relations began to improve at the close of the 1970s, when Moscow, faced with the U.S.-Chinese rapprochement, took steps towards restoring cooperation.

Since then, political and geostrategic expediency has driven gradual improvement in bilateral relations. During the 1989 Sino-Soviet summit in Beijing, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping urged the two countries to “put the past behind us” for the sake of future cooperation. His call was welcomed in Russia. The long process of rapprochement eventually led to the Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation (16 July 2001), and the Additional Agreement on the Russian-Chinese State Border in its Eastern Part (14 October 2004), which officially declared the absence of claims, including territorial ones, by either side. (Although China continues to view the treaties of 1858-1881 as “unequal,” and retains its prior understanding of the geography of the previously-disputed Ussuri-Amur region—see above).

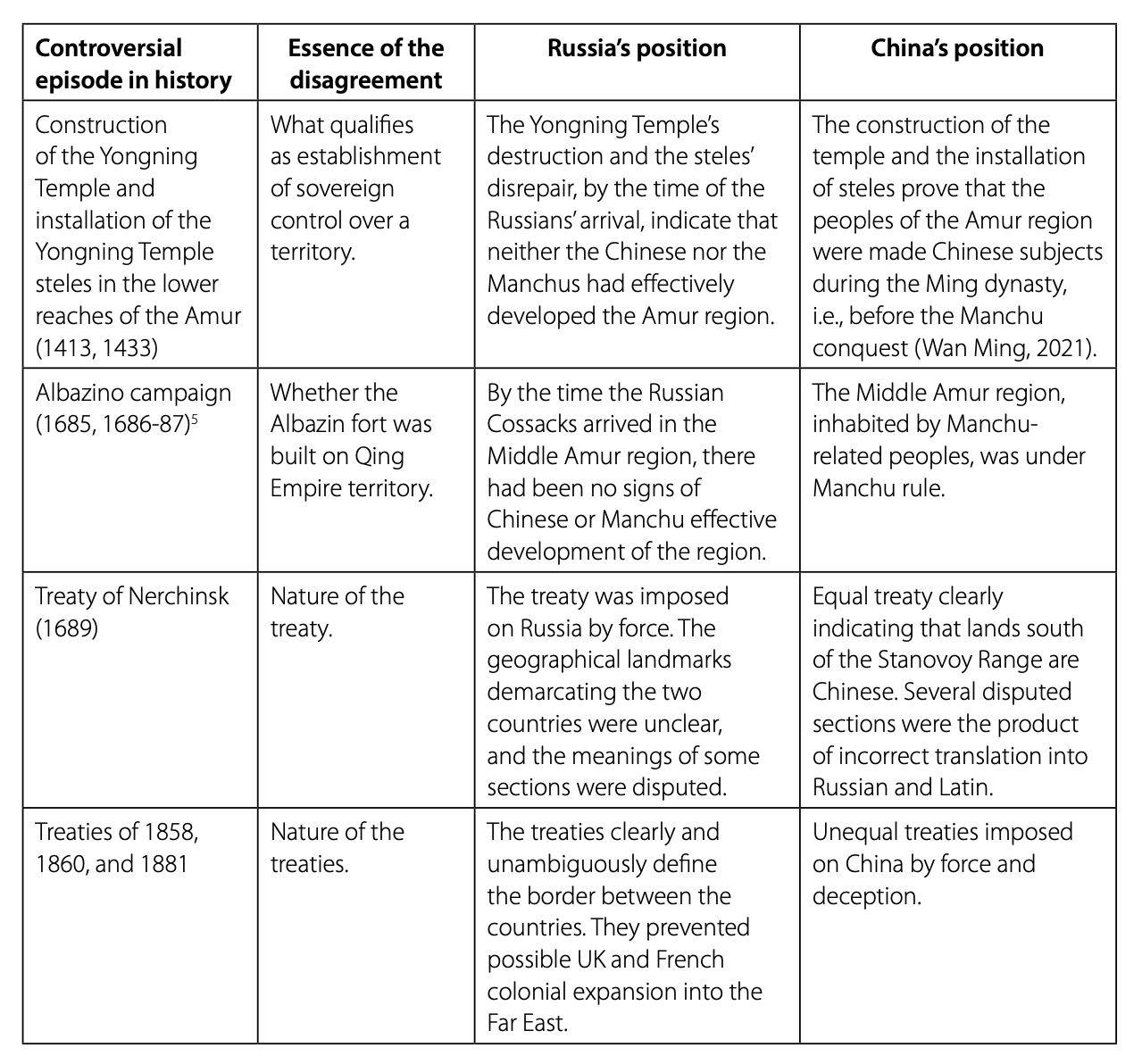

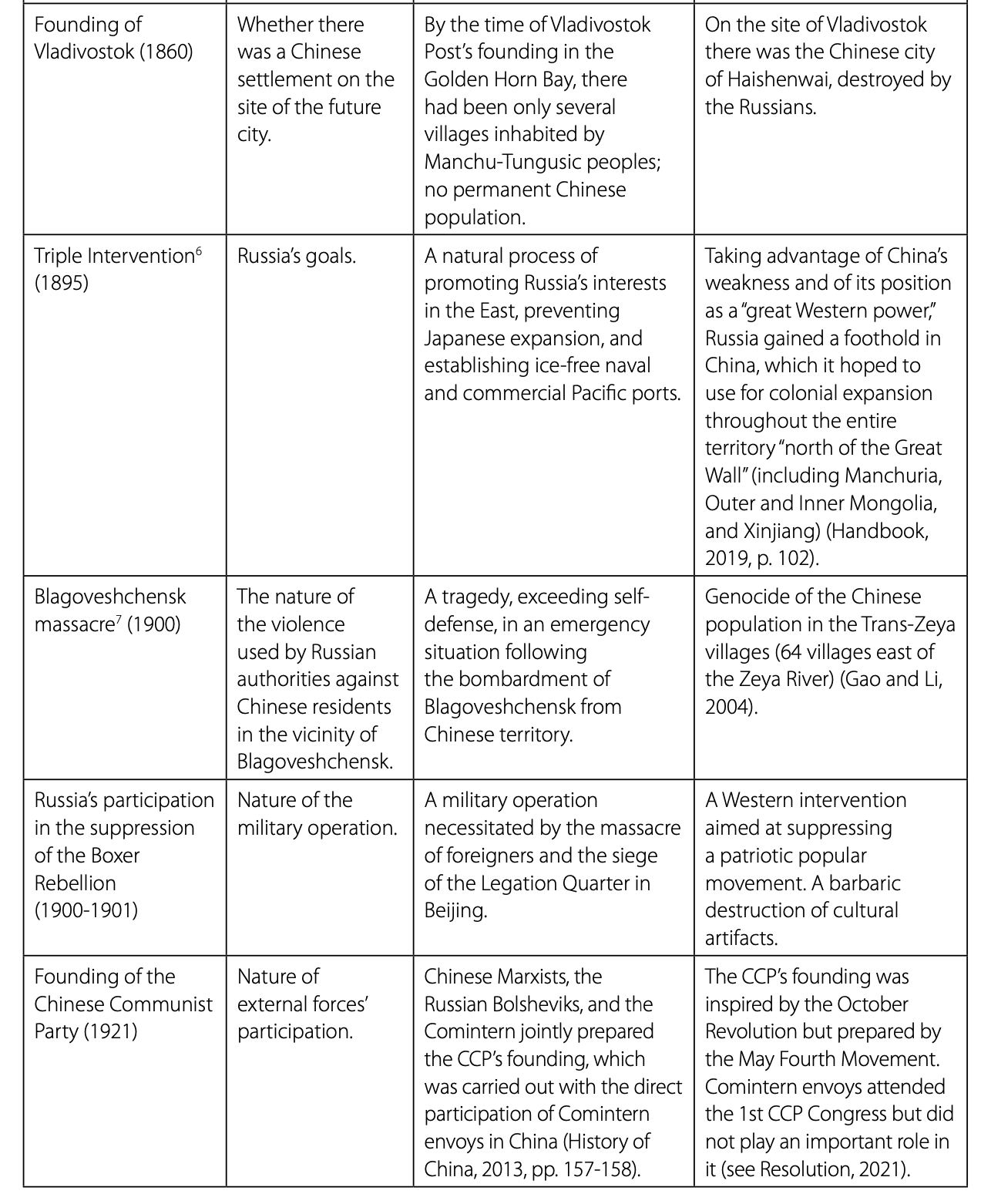

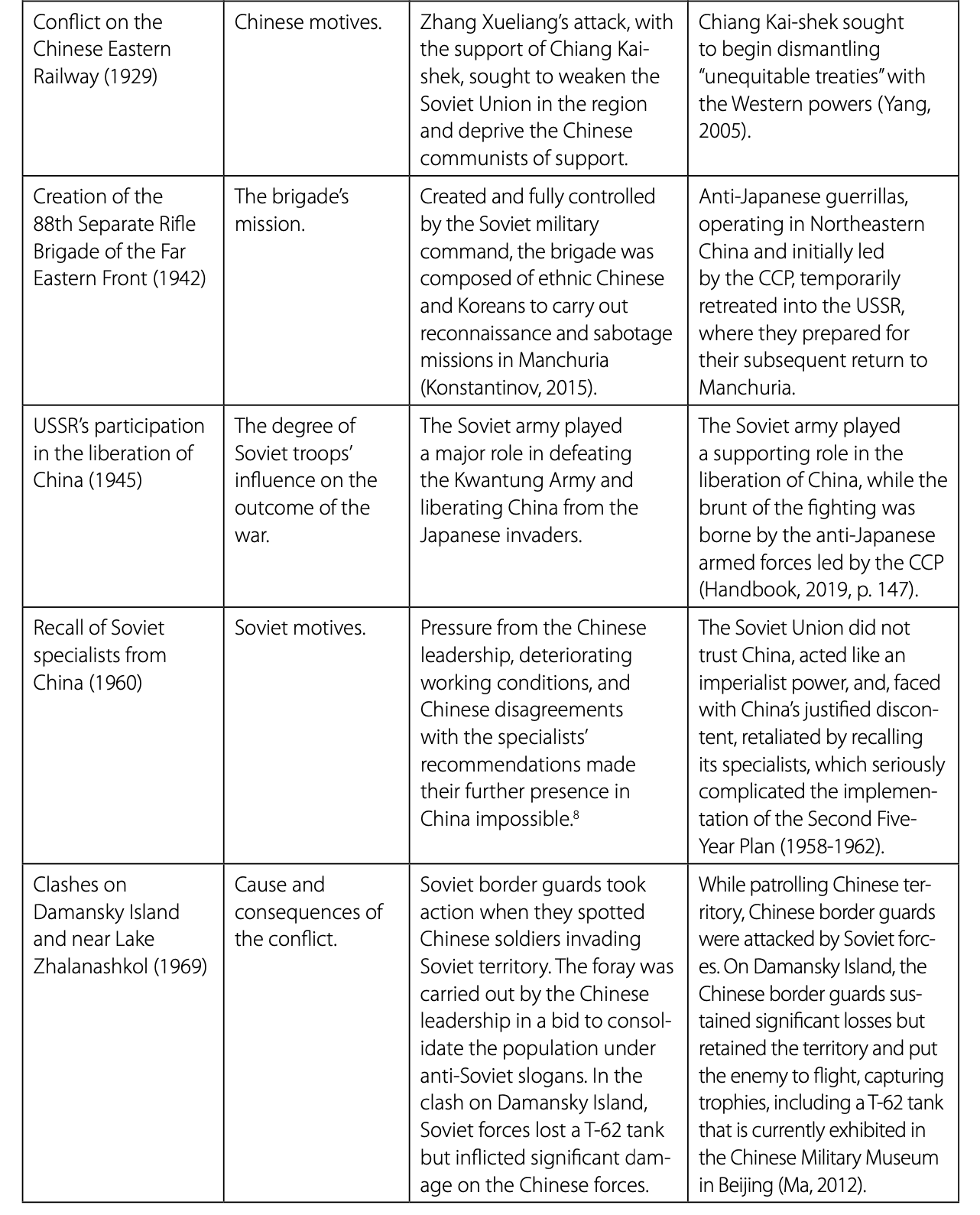

Thus, political expediency outpaces historiographical reflection and stipulates the selectively positive tone of official rhetoric about the “inconvenient past.” Complex issues are not examined and are even hushed up. As a result, as of today, there are several episodes subject to divergent perceptions by the two countries:

Strengthening China’s National-Patriotic Sentiment Under Xi Jinping

The first decade of the 21st century saw the full emergence of the current situation, in which contradictory understandings of crucial historical episodes coexist with a high level of Russian-Chinese partnership and an absence of official claims. However, this situation is jeopardized by rising nationalist sentiment in both countries. In our opinion, it is more pronounced in China, warranting a separate analysis.

By the beginning of the 2010s, China was nearing a systemic socio-political crisis. Rapid economic growth—sustained by market reforms, export orientation, and extensive cheap labor—had come to an end. Rising living standards and broad access to information spurred demand for further reform. At the same time, the passivity of the “fourth generation of leaders” (Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao, etc.), who actually sabotaged long-overdue economic reform and overlooked income inequality and corruption, eroded people’s loyalty to the Communist Party.

So, to spare China the Soviet Union’s fate, Xi Jinping, elected General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee in October 2012, decisively “tightened the screws” in almost all spheres of life: from strengthening the party to tightening the rules of stay for foreigners. One of the government’s priorities in the ‘New Era,’ as Xi’s rule would be later termed, was intensified ideological and educational programming, especially in support of patriotic and nationalist values (Klimeš and Marinelli, 2018).

The Chinese Dream (of the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation; 中华民族伟大复兴), articulated by Xi in November 2012, became the ideological template for this effort.

Although many of the slogans declared during Xi’s decade of rule have gradually disappeared from official rhetoric, the Chinese Dream is still actively cited by the country’s leadership.

At the same time, there is no clear definition of the Chinese Dream. The most popular understanding defines the Dream as China’s return to the position of world leader that it held throughout most of history. Yet other interpretations focus on the concept of Zhonghua minzu 中华民族 (Chinese nation), implying a nation-state in which the coexistence of the Han and 55 ethnic minorities is replaced with a melting pot.

Both interpretations suggest that Chinese ideologists view the Chinese nation as being in crisis. They refer to a continuing Century of Humiliation (beginning with the First Opium War in 1842) and to national suffering, primarily during the war with Japan (1937-1945). So revanchism becomes the main principle underlying ideological and patriotic work.[9] Despite China’s obvious successes during the reform period, the people are told that this is insufficient and they must rally more actively around the CCP and its “core”—Xi Jinping—in order to realize the Chinese Dream. The “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” will follow.

These efforts include the development of a clear standard for understanding historical issues, including the “rectification” of Chinese history (Khubrikov, 2022). (The Confucian term zhengming (正名), “rectification of names,” is fitting here.) A major step in this process is the landmark Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century (中共中央关于党的百年奋斗重大成就和历史经验的决议), adopted at the Sixth Plenary Session of the 19th CPC Central Committee in November 2021. This document, prepared by a team directly headed by Xi Jinping, is the third version of the CCP’s comprehensive history.[10] Its main purpose is the consolidation of the authority of Xi Jinping, portrayed as a leader equal only to Mao Zedong.

Although the Resolution addresses mainly domestic issues, comparison to similar documents from 1945 and 1981 reveals some changes in the perception of other countries and of China’s historical relations with them. Russia and the USSR are mentioned in the 2021 Resolution three times:

- the Resolution repeats canonical wording, characteristic of previous historical documents, that “with the salvoes of Russia’s October Revolution in 1917, Marxism-Leninism was brought to China” (Resolution, 2021), while the Comintern’s role in the CCP’s founding, invariably emphasized by Russian historians, remains unmentioned, as before;

- the Resolution further mentions the October Revolution to state that copying the Soviet experience without accounting for Chinese realities was counterproductive (“in view of objective conditions at the time, the Chinese communists could not follow the example of Russia’s October Revolution and win nationwide revolutionary victory by taking key cities first”) (Ibid);

- our country is mentioned for a third time when, speaking of the challenges that faced the CCP at the turn of the 1980s and the 1990s, the Resolution names the USSR’s disintegration as the most important geopolitical factor.

It must be noted that the Resolution fails to mention important episodes like the USSR’s role in the defeat of Japan and its comprehensive assistance to China’s socio-economic development in the 1950s.

Regarding the defeat of Japan, the document reads: “The Party led the Eighth Route Army, the New Fourth Army, the Northeast United Resistance Army, and other forces of the people’s armed resistance in brave fighting, and they were the pillar of the entire nation’s resistance until the Chinese people finally prevailed. This marked the first time in modern history that the Chinese people had won a complete victory against foreign aggressors in a war of national liberation and was an important part of the global war against fascism.” This contrasts with the 1981 resolution: “the Chinese people were able to hold out in the war for eight long years and win final victory, in co-operation with the people of the Soviet Union and other countries in the anti-fascist war” (Resolution, 1981).

Soviet support for China’s postwar development is not mentioned, either: the CPC “stabilized prices, unified standards for finances and the economy, completed the agrarian reform, and launched democratic reforms in all sectors of society. It introduced the policy of equal rights for men and women, suppressed counter-revolutionaries, and launched movements against the ‘three evils’ of corruption, waste, and bureaucracy and against the ‘five evils’ of bribery, tax evasion, theft of state property, cheating on government contracts, and stealing of economic information. As the stains of the old society were wiped out, China took on a completely new look.” The 1981 resolution, in contrast, stressed the assistance of the Soviet Union and “other friendly countries” in implementing the First Five-Year Plan: “we likewise scored major successes through our own efforts and with the assistance of the Soviet Union and other friendly countries” (Ibid).

There is thus a clear tendency towards the erasure of external contributions to the CCP’s military and socioeconomic achievements. Memory of Russia’s positive role in the history of China and the CCP is suppressed and, at this rate, will disappear from public discourse completely (Denisov and Zuenko, 2022). What is most striking is that this is happening during the rule of a leader whose role in Russian-Chinese relations can only be acclaimed.

This is one of the paradoxes of current Russian-Chinese relations that was described at the beginning of the article and is corroborated by other research on memory politics (e.g., Chinese school textbooks (Rysakova, 2022)). It transforms all the skeletons in “the cupboards of history” into potential time bombs ready to detonate if the political situation sharply changes (e.g., due to leadership transfers).

Conclusions for Russia

Judging from Chinese media, there are two main reasons why the history of Russian-Chinese relations is presented in such a contradictory way:

- the division of Russia as a historical subject into “tsarist Russia” and “modern Russia” permits criticism of the former as an “expansionist and colonial power,” without questioning cooperation with present-day Russia;

- the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s and the 1970s, during which Russophobia was actively incited, continues to affect modern discourse.

In addition, some anti-Russian Taiwanese, Hongkonger, and overseas Chinese intellectuals post online articles on Chinese history, which are generally accessible in mainland China. The Ukraine conflict has created the opinion that rapprochement with Russia leaves China no chance for normalizing relations with the West, which these intellectuals see as the best option for China’s development. This contributes to the formation of a negative image of Russia in some segments of the Chinese population.

In general, there are currently two clear trends in the Chinese media:

- stimulating patriotic sentiment, to which end China is portrayed as a victim of Western colonial powers, including “tsarist Russia”;

- praising the CCP and China at home, to which end the USSR’s positive role in the CCP and the PRC’s development is belittled or entirely suppressed.

This process is accompanied by the negative depiction of Russia/the USSR and by the presentation of historical interpretations that directly contradict Russia’s.

As before, China regards the Russian Empire’s actions as “colonial expansion” and insists that the treaties were concluded by force and deception, as a result of which “a million square kilometers of Chinese territory” were lost. However, as the Chinese themselves say, this does not mean that Beijing expects the treaties to be revised and the “lost territories” to be recovered.[11]

The growth of patriotic sentiment in China, which could potentially be associated with revanchist aspirations directed at Russia, is the result of the government’s efforts to consolidate Chinese society. Such sentiment’s occasional transformation into Russophobia is a side effect that is likely unwanted by the Chinese authorities, who demonstrate a clear desire to suppress the most painful historical episodes, primarily the Blagoveshschensk massacre. (Perhaps the only exception is an exhibition at the Aigun History Museum: unveiled back in the 1970s, it continues to be regularly updated and supported by the government (Matten, 2013; Adda and Lin, 2022; Zuenko, 2024).)

Such a pragmatic attitude presumably stems from the need to legitimize the CCP. Portrayals of Russia as an “aggressor” imply that all previous generations of Chinese leaders were wrong—including Mao Zedong, who entertained claims on the Soviet Union but never made them officially, Deng Xiaoping, who proposed in 1989 to “put the past behind us and open up a new era,” Jiang Zemin, who explicitly dropped all claims to the “lost territories,” and Hu Jintao, who continued the policy of strategic partnership with Russia. Explicitly pandering to Russophobic sentiment runs counter to the interests of the ruling Chinese elite. Conversely, the topic of the “lost territories” seems to be one of the most effective ways to accuse the CCP of betraying national interests.

The policy of stimulating patriotic and nationalist sentiment in China may have far-reaching consequences if new leaders come to power. Public opinion is already potentially readied for a revision of relations with Russia, due to the focus on China’s past defeats and humiliations (including at the hands of Russia), at the expense of attention to positive chapters in Russian-Chinese history. Beijing’s political will is the main barrier to widespread Russophobia. The most effective strategy for Russia would be memorialization of the Far East’s development and of the peaceful periods of Russian-Chinese interaction, coupled with measured diplomacy, as a harsher approach can only ignite Chinese revanchism.

This paper is part of Russian Science Foundation Project #23-18-00109 “Historical Grievance Narratives in the Official Discourse and Public Policy of Northeast Asian Countries.”

References

[1] Notably, in the 2004 negotiations over the disputed Bolshoi Ussuriysky and Tarabarov Islands, the parties both made concessions, but did not relinquish their divergent interpretations of the disputed area’s geography. Russia still defines the Amur River as running both to the north and the south of Bolshoi Ussuriysky Island. (Great Russian Encyclopedia, 2017: https://old.bigenc.ru/geography/text/4702567). China still traces the Amur only to the island’s north, thus placing the island itself entirely to the river’s south. (e.g. https://baike.sogou.com/m/fullLemma?lid=36352). Russia’s renunciation of several islands at the confluence of the Amur and Ussuri Rivers, and China’s relinquishment of claims to the rest, should thus be viewed as gestures of mutual trust and willingness to compromise. This stands in stark contrast to the Russian-Japanese territorial dispute, where the parties refused to compromise even during the “thaw” in their relations.

[2] An exception is the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion, during which Russian troops under the command of General Linevich stormed Beijing in August 1900, suffering 26 killed and 106 wounded. Although the conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway in 1929 stands out in terms of casualties (281 killed, 729 wounded), it was peripheral for both China and the USSR.

[3] The creation of the state of Manchukuo (1932-1945), which official historiography calls a pro-Japanese “puppet” state (in Chinese, the character 伪, meaning fake, is used), can be considered an attempt to restore Manchu statehood.

[4] A typical example is the YouTube videos by a Chinese man living in New Zealand and known as Teacher Da-Kang (大康老师), and others. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTtudUajaY8&t=633s.

[5] The Chinese term is Yakesa zhanyi (雅克萨战役), where Yakesa is the name for Albazino.

[6] Since this episode is barely considered in Russian historiography as a distinct event, I use a calque from the Chinese term 三国干涉还辽, referring to the 7 April 1895 Russo-Franco-German demands that Japan revise the Treaty of Shimonoseki, as a result of which Russia received a lease of the Liaodong Peninsula.

[7] Absent an established Russian historiographic term, this one is proposed. China uses the term Gengzi E nan (庚子俄难), where Gengzi refers to 1900 as the “the year of the white rat,” and E means Russia.

[8] This position was most vividly expressed by outstanding Russian Sinologist Yuri M. Galenovich: “Responsibility for the departure of our specialists from the PRC rests entirely with Mao Zedong” (Galenovich, 2011, p. 201). It is appropriate to note here that Galenovich is the author of several works closely related to this article (see Galenovich, 1992; 2015), but in later works he adopted a firm anti-Chinese position, which was probably due to the peculiarities of his biography and the upheavals he experienced during the excesses of the Cultural Revolution when he worked in China. This circumstance makes his assessments quite subjective.

[9] Revanchism here means a country’s desire to regain what was lost in a defeat or crisis—not necessarily a defeat brought about by its own aggression (contra the Great Soviet Encyclopedia), and not necessarily a reacquisition via war. In the case of modern China, revanche means the restoration of Chinese civilization to its previous leading global position—although, as nationalist sentiment grows, revanche may also begin to imply territorial expansion.

[10] Earlier historical resolutions were adopted in 1945 and 1981: the resolution of 1945 stated the party’s history before its seizure of power; the resolution of 1981 provided an interpretation of the Mao Zedong era in the context of incipient reforms.

[11] See, for example, the following statement by renowned Chinese scholar of Russia, Yang Cheng: “If you look at historical maps, then tsarist Russia, indeed, took part of our territory, occupied it, but can we ignore and forget all the events of the past today? This is history, but we cannot rewrite it, we do not have such a tradition. <…> We signed the Treaty of Aigun, and we implement it” (Velesyuk, 2015).

_____________________

Adda, I. and Lin Yuexin, 2022. Geopolitics in Glass Cases: Nationalist Narratives on Sino-Russian Relations in Chinese Border Museums. Europe-Asia Studies, 74(6), pp. 1051-1081.

Denisov, I. and Zuenko I., 2022. Novye podkhody Pekina k istoriografii KPK i KNR: “ispravlenie imyon” v epokhu Si Tszinpina [Beijing’s New Approaches to the Historiography of the CPC and PRC: zhengming in the Xi Jinping Era]. Oriental Studies, 5 (4), pp. 734-750. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31696/2618-7043-2022-5-4-734-750.

Galenovich, Yu., 1992. “Belye pyatna” i “bolevye tochki” v istorii sovetsko-kitaiskikh otnosheniy [“Blind Spots” and “Sore Points” in the History of Soviet-Chinese Relations]. Moscow: RAN.

Galenovich, Yu., 2011. Rossiya v “kitaiskom zerkale”. Traktovka v KNR v nachale XXI veka istorii Rossii i russko-kitaiskikh otnosheniy [Russia in the “Chinese Mirror”. Interpretation of History of Russia and Russian-Chinese Relations in China at the Beginning of the 21st Century]. Moscow: Vostochnaya kniga.

Galenovich, Yu., 2015. Kitaiskie pretenzii: shest’ krupnykh problem v istorii vzaimootnosheniy Rossii i Kitaya [Chinese Claims: Six Major Problems in the History of Russia-China Relations]. Мoscow: Russkaya panorama.

Gao Yongsheng and Li Xunbao, 2023. [高永生,李寻宝], 2004. “庚子俄难”时限的再界定与思考 [New Analysis and Reflection on the “Gengzi Enan” Incident]. 黑龙江史志 [Journal of Heilongjiang History]. Available at: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-HLSZ20040300J.htm [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Handbook, 2019. 学生学习用书:历史 [Handbook for History Teachers]. Beijing: Renmin jiaoyu chubanshe.

History of China, 2013. Istoriya Kitaya s drevneishikh vremyon do nachala XXI veka. Tom 7. Kitaiskaya Respublika (1912-1949) [History of China from Ancient Times to the Beginning of 21st Century. Vol. 7. Chinese Republic (1912-1949)]. Moscow: Vostochnaya literatura.

Khubrikov, B., 2022. Istoricheskaya politika v sovremennom Kitae: konstruiruya proshloe, voobrazhaya budushchee [Historical Politics in Contemporary China: Reconstructing the Past, Imagining the Future]. International Analytics. 13(3), pp. 145-156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.46272/2587-8476-2022-13-3-145-156.

Klimeš, O. and Marinelli, M., 2018. Introduction: Ideology, Propaganda, and Political Discourse in the Xi Jinping Era. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 23, pp. 313-322.

Konstantinov, G (comp.), 2015. Osobaya internatsionalnaya 88-ya otdelnaya strelkovaya brigada Dalnevostochnogo fronta [Special International 88th Independent Rifle Brigade of the Far Eastern Front]. Khabarovsk: Priamurskie novosti.

Ma, Fuying, 2012. 马富英. 中俄关系中的边疆安全研究 [Research on Border Security Issues in Sino-Russian Relations]: PhD Thesis. Beijing: Central Nationalities University. Available at: https://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10052-1012416693.htm [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Matten, M. (ed.), 2013. Places of Memory in Modern China: History, Politics, and Identity. London: Brill.

Putin, V., 2023. Vladimir Putin’s Article for People’s Daily, “Russia and China: A Future-Bound Partnership”. Kremlin.ru, 19 March. Available at: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/70743 [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Resolution, 1981. 关于建国以来党的若干历史问题的决议 [Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China]. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/test/2008-06/23/content_1024934.htm [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Resolution, 2021. 中共中央关于党的百年奋斗重大成就和历史经验的决议(全文) [Resolution of the CPC Central Committee on Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century: Full Text]. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-11/16/content_5651269.htm [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Rysakova, P., 2022. “Rasskazat’ istoriyu Kitaya”: novatsii v shkolnom prepodavanii istorii v KNR v 2010-2020-kh gg. [“Telling China’s History”: Innovations in School History Education in PRC in the 2010s-2020s]. Oriental Studies, 5(4), pp. 751-772.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31696/2618-7043-2022-5-4-751-773.

Velesyuk, A., 2015. Pretenzii Kitaya na Dalniy Vostok — eto nadoevshiy anekdot [China’s Claim to the Far East Is an Annoying Joke]. Amurskaya pravda, 30 June. Available at: https://ampravda.ru/2015/06/30/print058469.html [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Wan Ming, 2021. 万明. 明代永宁寺碑新探——基于整体丝绸之路的思考 [New Research of Ming Dynasty Stelas of Yongning Temple – Analysis of Complexity of Silk Road]. 历史地理研究 [The Chinese Historical Geography]. Available at: https://hangchow.org/index.php/base/news_show/cid/8632 [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Wang Xiaoquan, et al., 2023. 王晓泉. 中俄关系的历史逻辑,相处之道,内生动力与世界意义 [The Historical Logic, Ways of Getting Along, Endogenous Motivation and World Significance of Sino-Russian Relations]. 俄罗斯学刊 [Russian Studies], Vol. 2, pp. 22-52.

Yang Kuisong, 2005. 杨奎松. 蒋介石、张学良与中东路事件之交涉 [Chiang Kai-shek, Zhang Xueliang and Negotiations after 1929 Sino-Soviet Conflict]. 近代史研究 [Modern History Studies], Vol. 1, pp. 137-316.

Zuenko, I., 2020. Kitaitsy o yubileye Vladivostoka: “Posolstvo Rossii unizilo Kitai” [The Chinese about the Anniversary of Vladivostok: “The Russian Embassy Humiliated China”]. Argumenty i fakty, 15 July. Available at: https://vl.aif.ru/society/a_byl_li_hayshenvay [Accessed 1 November 2023].

Zuenko, I., 2024. Muzei i memorialnye ob’ekty v rossiisko-kitaiskom transgranichye: perspektivy sozdaniya “kompromissnoi” versii obshchei istorii [Museums and Memorial Objects in Russo-Chinese Cross-Border Area: Prospects for Creating a Compromise Version of Common History]. Comparative Politics Russia, 14(3), pp. 24-40.

By Russia in Global Affairs | Created at 2024-10-29 18:21:54 | Updated at 2024-10-30 05:27:10

4 weeks ago

By Russia in Global Affairs | Created at 2024-10-29 18:21:54 | Updated at 2024-10-30 05:27:10

4 weeks ago