Ever since 2016, Americans have been struggling with the political rifts in their families over Donald Trump, concerns that have reached a fever pitch since the election. It’s the “what do I do about Uncle George?” problem. Accept our differences without talking about them, argue and try to change his mind, bar him from holiday dinners, never invite him over again until he sees the light? I grew up in a family where political opinions ranged from socialist to conservative; where religious beliefs ranged from none to very; and where arguments, including hot-button topics of Vietnam, Ronald Reagan and the Iraq war, often grew noisy and heated. But none of us ever detested a family member we disagreed with, let alone ostracized said relative. “He’s stupid, uninformed, and pigheaded, sure,” we might say, “but I love the bastard anyway. He’s also a great husband and dad, generous to the core, and very funny.”

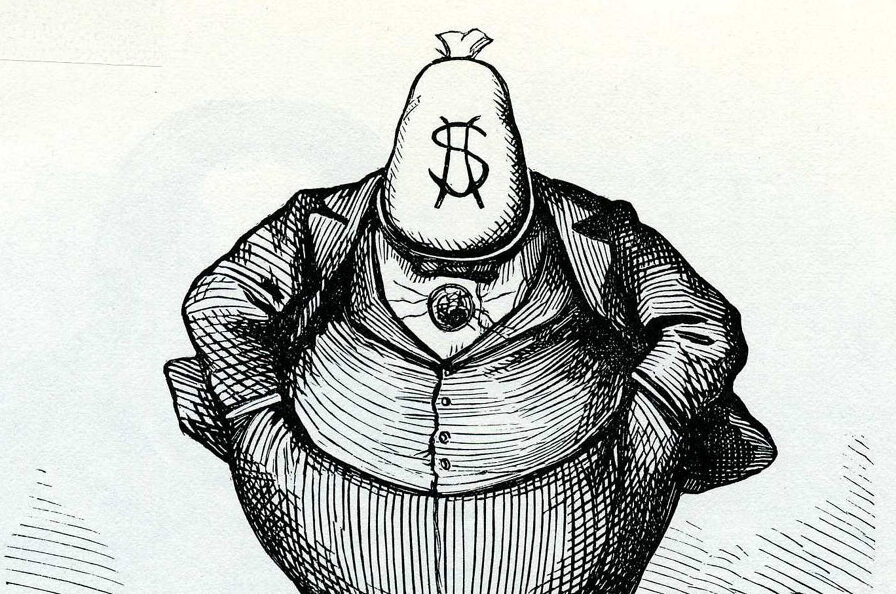

The left-right, liberal-conservative political divide is both universal and timeless, what Ralph Waldo Emerson noted as “an irreconcilable antagonism” in human nature. The left thinks conservatives have no heart; the right thinks liberals have no brains. But in American politics, that familiar polarization has morphed into something uglier and more dangerous, thanks to the rise of an uncompromising Republican strategy that began with Richard Nixon in the early 1970s and was explicitly expanded by Newt Gingrich in the 1980s. This strategy was actually called “positive polarization”: the more divided the country, its proponents believed, the better for their party, because “it stoked the anger they needed to get their voters to turn out”. In the past decade, of course, political polarization has become even more extremely entrenched, thanks to the ubiquity of social media.

Simultaneously, on an individual level, it has become harder – and for many, impossible – to tolerate differences of political opinion precisely because politics is no longer a matter of opinion but of identity. Researchers have documented that large numbers of people in both parties now regard their opponents as being not only stupid, uninformed, and pigheaded, but evil incarnate – the kind of person you would never have in your home or family.

It stands to reason – not that reason is in abundance these days – that kind, tolerant, thoughtful psychologists would try to figure out how people can persuade each other to be kind, tolerant and thoughtful. How can we learn the gentle art of persuading our opponents of their flaws and errors of reasoning and even learn to acknowledge our own, assuming we have any, which of course we don’t? And how in the world can we do this when the world has become a sea of misinformation, lies, conspiracies, and delusions?

Enter numerous books with hopeful solutions, among them Joe Pierre’s False: How mistrust, misinformation, and motivated reasoning make us believe things that aren’t true, and Kenneth Barish’s thin entry on a complex problem, Bridging Our Political Divide: How liberals and conservatives can understand each other and find common ground. Pierre, a psychiatrist, reviews the brain’s myriad cognitive biases that create delusions and conspiracies – the psychotic ones and the “normal” ones – and the “disinformation industrial complex” that preys on them. This is hardly a new story, but it always bears repeating, especially for anyone who does not know what the confirmation bias is. I have a shelf of books on the brain’s cognitive biases, including my own entry, with Elliot Aronson, on cognitive dissonance as the basis of motivated reasoning. My personal favourite cognitive bias is what social psychologist Lee Ross called “naive realism”, the belief that we see things clearly, “as they really are” and that it is everyone else who is biased. This bias makes dinner-table debate challenging, to say the least.

Pierre, a psychiatrist, and Barish, a clinical psychologist, bring their experiences with therapy clients and the lessons of cognitive science to show how the mind’s built-in biases block empathy and understanding, and how individuals and couples can learn to listen to another’s convictions, learn to debate constructively, and find common ground. No one can dispute the value of having such skills, and Barish and Pierre make a spirited case for why we should want to engage in debating and listening to the opposition, when it feels like most people on both sides don’t want to.

They don’t want to try yet again to persuade Uncle George out of his conspiracy theories and certainty that Democrats “stole” the 2020 election. They don’t have the energy to try to persuade cousin Harriet that not all Trump voters are fascist misogynist white supremacists but, like many disaffected Democrats, legitimately concerned about immigration law, lack of affordable housing, and the price of groceries – topics under the radar in Kamala Harris’s campaign. Even if we could acquire the persuasive skills of Cicero, how would we get our friends and relatives to want to listen to disconfirming arguments, after the years of allowing the confirmation bias and their favorite news show to encrust their barnacles of belief? Do we want to risk dislodging our own barnacles? And how would we get our friends and relatives to want to listen to arguments that might make them question their identity as a righteous warrior for truth and justice – whichever side they are on – evidence against their opinion be damned?

No wonder, in the aftermath of this bitter election year, many winners have retreated to gloat and many losers have retreated to despair. Some on both sides are choosing to end decades-long friendships rather than risk the discomfort of talk, anger and loss. One Democrat told me that his closest friend of 40 years became a MAGA Republican and now regards his old pal, a union rep all his life, as “the liberal elite” – and has ghosted him. Another Democrat said she will no longer see an old friend who voted for Trump. “That tells me more about his morals, values, and prejudices than I can tolerate”, she said.

Barish and Pierre overlook the two biggest challenges for those who want to find common ground across enemy lines. One is that George and Harriet don’t necessarily know why they hold their points of view. Because most people see themselves as being wise, competent and informed, they will justify their beliefs as being wise and validated, even if they haven’t spent one second studying proposed immigration solutions around the world, or read the Cass report on pausing transgender surgeries for minors, or pored over Project 2025’s terrifying plans for a Trump presidency. They won’t admit the more likely reasons for their beliefs, including “I’ve been in an information silo for 8 years”, or “Everyone in my family, university, or church thinks this way” or “I trust my primary news source and my really smart father-in-law to give me the truth”. How likely now are they to admit, “Say, you’re right; I’ve been letting my support for [fill in the political or activist organization] and my hours spent online being enraged by [fill in the fear-mongering podcaster] and my affection for my father-in-law do my thinking for me”? How likely are they even to say, “the fact is that the world is scary, and I feel lost and angry about the changes I see everywhere, that I’m thinking that only a strong guy can get us out of this mess”?

The second, even greater challenge for anyone who wants a politically polarized friendship to continue is to resist the impulse to demonize the other, generalizing from their one disagreeable opinion to all other domains of their lives and personalities. Cognitive dissonance makes this effort uncomfortable because it causes us to live with two dissonant cognitions: (1) I disagree profoundly with my friend’s opinion about Trump but (2) my friend helps weekly at a food pantry, changed my flat tire, and completely agrees with me on movie preferences. Several Democratic friends told me that when they were desperately ill, it was their Republican, Trump-voting neighbours who brought them soup and casseroles and walked their dogs; their liberal neighbours gave another check to the Harris campaign. Some rural Republicans have written about their shock at learning their Democratic neighbours aren’t crazy socialist traitors after all and even know how to use a snowplow and a backhoe. It took experience on the ground to help both sides discover that their ideological enemies are actually decent, moral, hardworking people who love their children and help their neighbours, and who share their concerns about, for example, living paycheck to paycheck, never being able to afford a house, watching their community torn apart by homelessness and drugs.

This is why Barish and Pierre have it backwards: changing our perceptions and biases doesn’t move us to find common ground; standing on common ground changes our perceptions and biases. Asheville, North Carolina, and its surrounding communities, all devastated by floods and Hurricane Helene last October, are being rebuilt and rejuvenated by “rednecks” and “libs” working together; people who would never have spoken to one another before the election now offer food, shelter, and construction help to any neighbour in need. On an individual level, therefore, the books we need now might best advise us to stop arguing with Uncle George and cousin Harriet altogether, and maintain whatever we enjoy about their company. Who knows? Their views, and ours, might even change over time.

Carol Tavris is a social psychologist and coauthor, with Elliot Aronson, of Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me), now in its third edition, 2020

The post Bridging the divide appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:29:17

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:29:17

1 week ago