Canada plans to partner with Australia to build its new Arctic Over The Horizon Radar (A-OTHR), a project with a current estimated cost of more than $4 billion. A-OTHR is intended to provide critical new early warning capabilities and otherwise help close radar coverage gaps over the ever-more strategic Arctic region.

Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney first announced the new details about the A-OTHR effort, as well as plans for the Canadian armed forces to increase its overall presence in the Arctic, yesterday. A-OTHR is part of a larger initiative to modernize the capabilities the country provides to the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) that authorities in Ottawa first rolled out in 2022.

Canadian Prime Minister seen during a meeting with his British counterpart Keir Starmer in London on March 17, 2025. Jordan Pettitt – WPA Pool/Getty Images Jordan Pettitt

Canadian Prime Minister seen during a meeting with his British counterpart Keir Starmer in London on March 17, 2025. Jordan Pettitt – WPA Pool/Getty Images Jordan Pettitt“Prime Minister Carney announced that Canada intends to partner with Australia to develop advanced Over-the-Horizon Radar technology,” according to a press release from the Canadian Prime Minister’s office. “This partnership will include developing Canada’s Arctic Over-the-Horizon Radar system, an investment of more than $6 billion [Canadian dollars; emphasis in the original] that will provide early warning radar coverage from threats to the Arctic.”

$6 billion Canadian dollars is approximately $4.18 billion U.S. dollars at the rate of conversion at the time of writing.

“A key component of Canada’s NORAD modernization plan, the radar system’s long-range surveillance and threat tracking capabilities will detect and deter threats across the North,” the release adds. “The Prime Minister confirmed the partnership in his call with the Prime Minister of Australia, Anthony Albanese, earlier today.”

“This was a one-on-one conversation. It was extensive. It was a good opportunity for us to get to know each other personally. Canada, of course, has an excellent relationship with Australia,” Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said about the call with Carney at a press conference today. “One of the things that the Prime Minister [of Canada] confirmed is that he is looking at our, looking at what we have, which is our Jindalee Operational Radar Network technology. This is a world leading technology.”

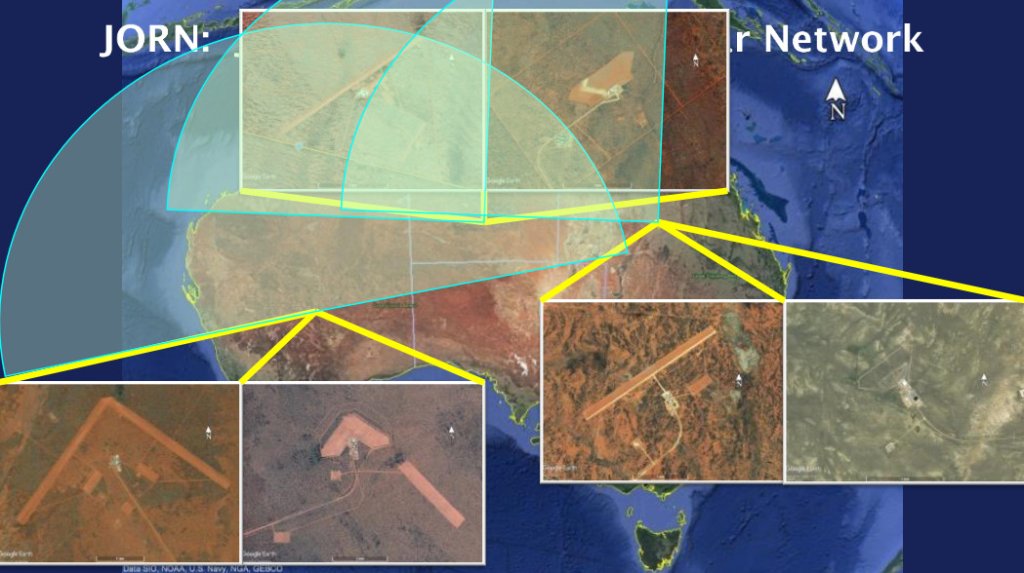

An aerial view of a portion of Australia’s Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN). Australian Department of Defense

An aerial view of a portion of Australia’s Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN). Australian Department of Defense “We want a future made in Australia and we want to export wherever possible. And this will be a significant export if this deal is finalized,” Albanese continued. “He [Carney] certainly spoke to me about the over-the-horizon radar technology that Canada is interested in purchasing from Australia.”

Australia’s Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN) consists of three separate over-the-horizon radars built in the country’s Queensland, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory starting in the 1990s. “JORN is designed to monitor air and sea movements across 37,000km [nearly 23,000 miles] of largely unprotected coastline and 9 million square kilometres [approximately 3.47 million square miles] of ocean,” according to a report from Defense Systems Daily in 2000.

The network is currently in the process of receiving major upgrades valued at $1.2 billion, with BAE Systems on contract to do the work. BAE says JORN, as it exists now, “provides wide-area surveillance at ranges of 1,000 to 3,000 kilometres [621 to 1,864 miles].”

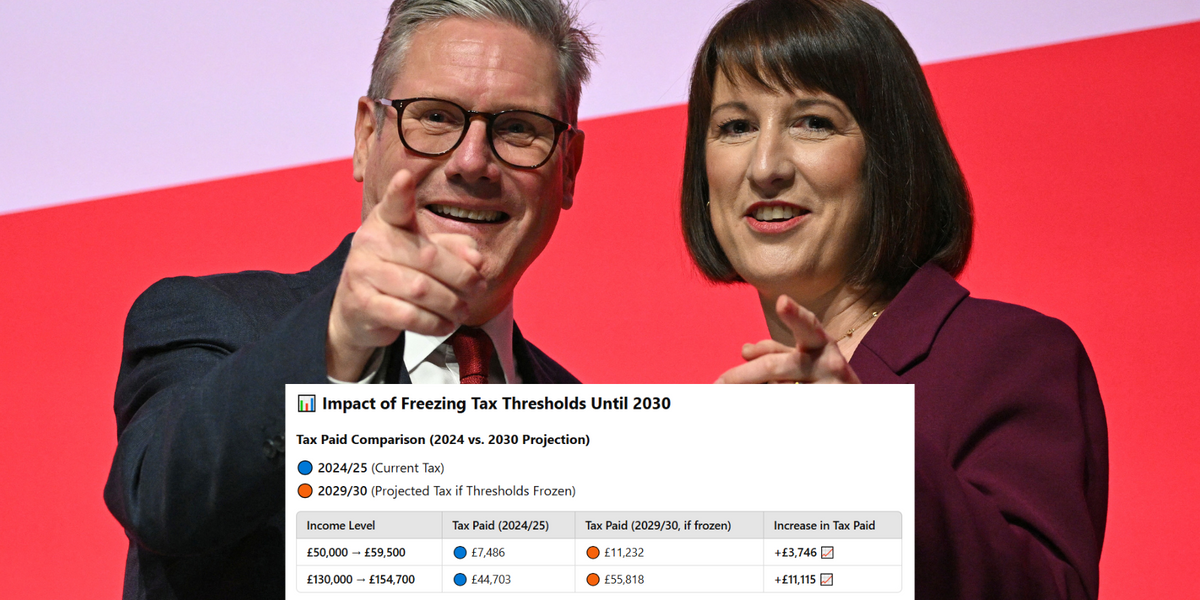

A slide from an Australian Defense Science and Technology Group briefing on JORN. Defense Science and Technology Group

A slide from an Australian Defense Science and Technology Group briefing on JORN. Defense Science and Technology Group All three of JORN’s radars are what are known variously as ‘backscatter’ or ‘sky wave’ types. As TWZ has explained in previous reporting on over-the-horizon radar developments:

“A traditional ‘sky wave’ or ‘backscatter’ over-the-horizon radar (OTHR) usually consists of a large array of antennas spread out over an area, and the transmission and receiver sites are usually geographically displaced. OTHRs possess the ability to detect targets at extreme ranges beyond what is known as the ‘radar horizon.’ Commonly, radars are limited by line of sight due to the curvature of the earth in relation to the altitude they are operating at. OTHRs overcome this critical limitation, but with some major drawbacks.”

“OTHRs were commonly deployed throughout the Cold War, especially as part of early warning ecosystems, but started to become less relevant for some applications after the war ended. More recently, these large static systems have been coming back into style thanks to major geopolitical shifts, advancements in computing power, and the value proposition they provide.”

“While they offer much lower fidelity than many of their line-of-sight counterparts in most cases, they make up for it in huge range, hundreds of miles to thousands of miles (1,500 miles is common, for instance, for powerful military sky wave/backscatter OTHR systems) and a large coverage area. The sky wave type of OTHRs achieve this by bouncing their radio waves off the ionosphere to a coverage area where they hit targets and return the same way to the receiving station. The angle at which the radio waves hit the ionosphere dictates the range, and that angle is limited to a specific envelope or the waves won’t properly bounce back toward earth. As such, placing the radar in the right place in relation to the targeted surveillance area or areas, to begin with, is key.”

An annotated map from the Australian Defense Science and Technology Group briefing showing JORN coverage arcs and satellite images of the main transmitter and receiver sites. Australian Defense Science and Technology Group

An annotated map from the Australian Defense Science and Technology Group briefing showing JORN coverage arcs and satellite images of the main transmitter and receiver sites. Australian Defense Science and Technology Group How many total arrays Canada’s final A-OTHR system might include, or when any part of it might become operational, is not entirely clear. A joint statement in 2023 from then-U.S. President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who resigned earlier this month, outlined a plan for “procuring and fielding two next generation Over-the-Horizon Radar (OTHR) systems covering the Arctic and Polar approaches,” with “the first [in place] by 2028 to enhance early warning and domain awareness of North American approaches.”

The Canadian Department of National Defense’s webpage on the A-OTHR currently estimates that the program will “start implementation” in the 2027/2028 timeframe. Initial and final delivery of the system is then expected to come in 2030/2031 and 2031/2032, respectively.

NORAD does have an array of ground-based radars pointed north now called the North Warning System (NWS), but none of them provide the kind of wide-area long-range coverage that an over-the-horizon design would offer. The NWS is also more truncated overall than its predecessor, the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, the result of post-Cold War drawdowns.

A map showing NWS radar sites in Canada and their coverage arcs. Nasittuq Corporation

A map showing NWS radar sites in Canada and their coverage arcs. Nasittuq Corporation Even just having one new over-the-horizon radar in Canada pointed north would give the command a huge boost in early warning coverage and general situational awareness in the Arctic region.

“We need a layered sensing grid, from [the] seafloor to the space layer. And we have no choice. It has to be layered and deep, a defense in depth, from a sensing point of view,” Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Maj. Gen. Chris McKenna, head of 1 Canadian Air Division and the Canadian NORAD Region, said back on March 4 during a panel discussion at the Air & Space Forces Association’s (AFA) 2025 Warfare Symposium, at which TWZ was in attendance. “And I will say I suffer from an insufficiency of ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] in the Arctic on a daily basis. And I am fighting for information.”

McKenna was responding to a direct question about gaps in so-called “domain awareness” in and around the Arctic and how to address them.

“I think there’s an importance here of not just air domain, but also space domain, and having a sufficiency of ISR in the Arctic to actually build you the [domain awareness] picture,” McKenna continued. “I haven’t really touched on over-the-horizon radar, but I certainly can get into it. I think that’s a really important capability given the austerity of the Arctic and the need for it to cue other things.”

RCAF Maj. Gen. Chris McKenna speaks at the Air & Space Forces Association’s 2025 Warfare Symposium. AFA capture

RCAF Maj. Gen. Chris McKenna speaks at the Air & Space Forces Association’s 2025 Warfare Symposium. AFA capture Monitoring for potential threats heading toward North America across the North Pole, including possible nuclear strikes from Russia (and the Soviet Union before it), has long been a key national security interest for both the United States and Canada. More recently, receding ice and other environmental changes in the Arctic due to global climate change have opened up a host of new avenues for geostrategic competition around natural resources, from oil and natural gas to fish and other sealife, as well as trade routes. China, America’s current chief global competitor, has been notably pushing to increase its presence in the High North in recent years, militarily and economically, often in cooperation with Russia.

At a hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee in February, NORAD’s top commander, U.S. Air Force Gen. Gregory Guillot, also highlighted how cooperation on enhanced domain awareness could be a pathway to Canadian participation in President Donald Trump’s massive new missile defense initiative, now dubbed Golden Dome.

“I welcome their participation. I think the first [point] would be to buy into our domain awareness expansion, whether ground-based or space-based,” Guillot said. “Then, further down the line, if they get [missile] defeat mechanisms, see how they would mesh with our existing defense mechanisms, defeat mechanisms, in a similar way that we employ fighter aircraft with NORAD. Perhaps we could do the same with missile defeat systems from the ground.”

At that time, relations between Canadian authorities and the new Trump administration were already strained and a full-on trade war has since broken out between the two countries. Canada’s decision now to partner with Australia on the A-OTHR, which reportedly came as something of a surprise, might in part reflect efforts to reduce reliance on U.S. firms.

An array of antennas at one of the JORN sites. BAE Systems

An array of antennas at one of the JORN sites. BAE Systems Whatever the case, Canada is working to take an important step forward in providing badly needed additional long-range radar coverage across the highly strategic Arctic region that will benefit both members of NORAD. It might also signal a new chapter in Canadian-Australian relations.

Contact the author: [email protected]

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-19 23:51:32 | Updated at 2025-03-20 15:25:14

15 hours ago

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-19 23:51:32 | Updated at 2025-03-20 15:25:14

15 hours ago