From May to September 2023, 11,500 screenwriters represented by the Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike. Their dispute – which concerned both the use of artificial intelligence and streaming residuals (payment for the reuse of their work by streaming services) – was with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. Since the WGA’s former president Victoria Riskin had agreed not to negotiate with the Alliance, twenty years earlier, film companies had been able to claim writers’ residuals for scripts written prior to 1960. On Riskin’s appointment as president, a press release had claimed that she was “the first woman President in guild history”. Neither then, nor during the subsequent strike, was the name “Mary C. McCall Jr.” mentioned.

In fact, McCall was the first woman president of the WGA, which was known at her election in 1942 as the Screen Writers Guild (SWG). Her tenure, unlike Riskin’s, was dedicated to the protection of screenwriters’ intellectual property and due remuneration. The first biography of McCall by J. E. Smyth uses her presidential position to dub her “Hollywood’s most powerful screenwriter”. The strike of 2023 is only mentioned once in Smyth’s conclusion, but it lends a vitality to the illuminating chapters preceding it. As more studios turn to AI for script-writing purposes, the art of a writer-for-hire such as McCall seems set to vanish.

The SWG formed in the early 1920s as a social club, and took on its union status in the wake of the Great Depression in 1933. The work of writers, as today, was treated without respect; much of McCall’s own work went uncredited. For her at least, the situation improved after 1934, when she was given a contract by Warner Bros. of $300 a week, $200 more than Dalton Trumbo. Trumbo’s name remains familiar to cinephiles, thanks in part due to being one of the Hollywood Ten blacklisted under McCarthyism and later the subject of a biopic starring Bryan Cranston (2015). McCall has been forgotten.

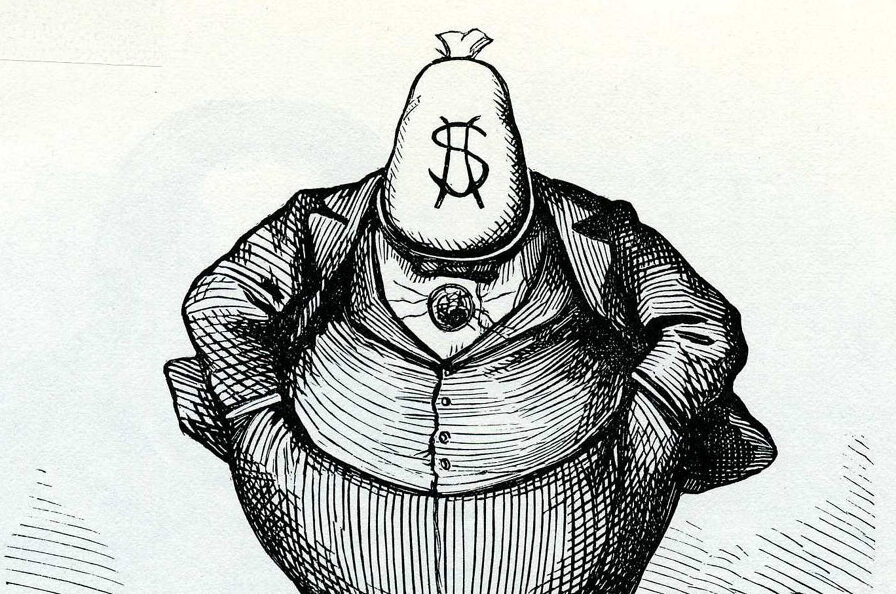

McCall had to assert her position in relation to men throughout her career. Born in New York in 1904, she studied at Vassar College and published a novel, The Goldfish Bowl (1932), that was filmed that same year as It’s Tough To Be Famous. Her prewar scripts included an adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) and the first in the long- running series of Maisie films (1939). Alongside this work came much negotiating on behalf of the WGA. When she was elected as president of the Guild for the third time in 1951, McCall had a striking photo shoot: perched on a desk next to a stuffed St Bernard, she wore a tweed blazer while holding a pipe and a pint of beer. Smyth reads this image as a pastiche of the traditional image of the great male writer, and an assertion of dominance over the boys in the room. McCall’s writing focus was distinctively female, however, shaped by the belief that audiences were less attracted to male-penned upper-class starlets than real stories of working-class women with whom they could identify. Maisie proved to be a sleeper hit, and launched Ann Sothern as a household name.

Not that McCall was alone – almost a quarter of SWG members in the 1930s were women. Smyth creates a rich portrait of 1930s Hollywood, relating her to more familiar names such as Anita Loos. The legacy of women writers tends to hinge on their proximity to Hollywood’s biggest stars, and although McCall’s words were spoken by the likes of Rosalind Russell and Barbara Stanwyck, she never had an enduring hit. She did come close to Marilyn Monroe with an uncredited polish job on There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954). Smyth relates that McCall asked of Monroe, “She needs dialogue?”

Given the scarcity of many of McCall’s films, Smyth does a fine job of recreating the screenplays for the reader. Most striking is the story of the melodrama Craig’s Wife (1936), scripted by McCall and brought to life by Dorothy Arzner, Hollywood’s sole full-time woman director at the time. Of her work on the film, McCall said, “Miss Arzner’s belief that a writer should be a part of the making of a picture from start to finish, and that I had the makings of a good writer for the screen, encouraged me to stay”. The two remained friends until Arzner’s death, and McCall found her time working with a woman director the most enjoyable and validating experience of her professional life.

It was television that killed McCall’s career, with her hopes of launching Maisie on the small screen swiftly dashed. Smyth traces her narrative with great care, and includes a number of remarkable plates cited as coming from her personal connection. The book is a love letter from one writer to another, and a rallying cry to Hollywood to return to the principles of its true first lady.

Lillian Crawford is a freelance writer

The post Credited at last appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:02 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:34:04

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:02 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:34:04

1 week ago