In 1962 Charmian Clift put aside her autobiographical novel to help her husband write his. For the past decade, she and George Johnston had been living in Greece, co-authoring little potboilers that barely paid the bills. But then Johnston became increasingly sick from tuberculosis, mortality impelling the need for self-preservation and therefore sole authorship. In their living room Johnston wheezed and wrote while Clift scrutinized every page. She even allowed Cressida Morley – the alter ego she had invented for herself – to appear first in Johnston’s novel.

In Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964), Cressida is a fleeting presence of sweetness – “the youngest thing I had ever seen in my life,” with a silky mouth and cheekbones “too heroic” – in an altogether morose portrait of Melbourne before and after the war. But in the sequel, Clean Straw for Nothing (1969), written without Clift’s input, Cressida is no longer a lovely cameo but a main player: the wife. In fragments Johnston assembled their ruinous, co-dependent romance; Cressida, decadent and Bovary-like, her infidelities speculated to be the cause of the narrator’s ailing health. “Given a taste of freedom she will want to drain the cup,” wrote Johnston. “It is her long denied right.” What about the right to one’s own fictive double? With the publication of Clift’s unfinished manuscript The End of the Morning earlier this year, Cressida has been repatriated.

The fifty or so pages that we have of the novel find Cressida recalling the profuse beauty and ferality of Kiama, the beach town south of Sydney where Clift grew up. Cressida takes us past the seaweed-shrouded fence and inside her family’s cottage for portraits of the Morleys: her father, boisterous and polemical, prone to reciting Rabelais; her mother, devoted and unfussed, too priggish to hang her wet underwear on the backyard line; her elder sister, Cordelia, unknowable but gorgeous, the favourite of the family; her brother, Ben, Cressida’s closest confidant, scurrying to cubby spots and leaping across sand dunes.

These are the beginnings of a Bildungsroman, where a girl is bound to flee the provincial paradise of her youth, desperate for metropolitan glamour. Its unfinished state means we’re left instead with a terrarium of childhood. Clift grabs our hand and encircles the glass jar. Look! Her prose commands. Here is the slimy moss of sibling jealousies. Over there? The stiff branch of familial worship. In the dirt is the secret, sloppy play of children, prone to perversity. Below is the rocky sediment of history, weighing on the present. This is Cressida’s small world, captured just before its smallness begins to burden; everything truly important is happening right there, at the Morley dinner table overflowing with nasturtiums, sauce boats and buttered cabbage.

Mornings in Kiama exist “under a thin, radiant dome-shaped cover,” the kind that encases “bridal wreaths, cake decorations from weddings and christenings, funeral ribbons, army biscuits carved with camels, sphinxes modeled from matchsticks, golden keys presented at twenty-firsts, babies’ shoes, and small bullet-dented bibles that had been worn over soldiers’ hearts”. Clift’s writing is loaded with lists like this – she loves the culmination of tiny, sensual details, the piling on of pleasure. The Australian writer Evelyn Juers, writing about Clift for this journal in 2005, wrote of her tendency to hoist “banderols of adjectives upon her nouns”.

Take the ocean, “so vast, so silky dark, so brilliantly glittering,” a “marvelous dark and exultant blue, so deep, so immense, so icy on even the hottest day”. In one passage, about riding a wave onto the shore, Clift similarly throws the reader with her jumble of descriptors: “To turn on a crest, belly sucked in, body a scoop, poised dizzily ten or fifteen feet up for that breathless sunbursting second before the wave nicked up one’s puny little body and hurled it down the glistering slope and on and on before in the wildest, most exhilarating ride that landed one stranded triumphantly on the sand”. But the author’s splendour is always a little sick, a little grotty. A local perv hobbles out of his house with a “snot-caked mustache”. Cressida falls asleep to the sound of her father’s piss splashing against the backyard fuchsia tree. This is the pungency of her prose; one can practically smell the sweet rot of squashed Moreton Bay figs.

In the last few pages of the book the lid of Cressida’s life is lifting, only slightly. Cordelia skips off to study art in the city, her skint parents bankrolling her studies to the future detriment of her siblings. But for Cressida her sister’s weekend visits bear the tang of a world beyond Kiama’s salty borders. Finally a future, sweeping and undefined, can be glimpsed. But then it’s all over, the book abruptly unfinished, Cressida trapped at the gate of pre-adolescence.

Clift was tortured by The End of the Morning. She had started on the book in 1962, but its origins stretch back to the mid-1940s, when she had begun her first attempt at autobiographical fiction. Throughout the 1960s the novel was written in small bursts, but routinely abandoned. In 1968, with a small government grant, she returned to the project, telling the Australian newspaper that the novel was “like an owl on my shoulders for years”. Less than a year later she committed suicide, a few weeks before the publication of Johnston’s Clean Straw for Nothing.

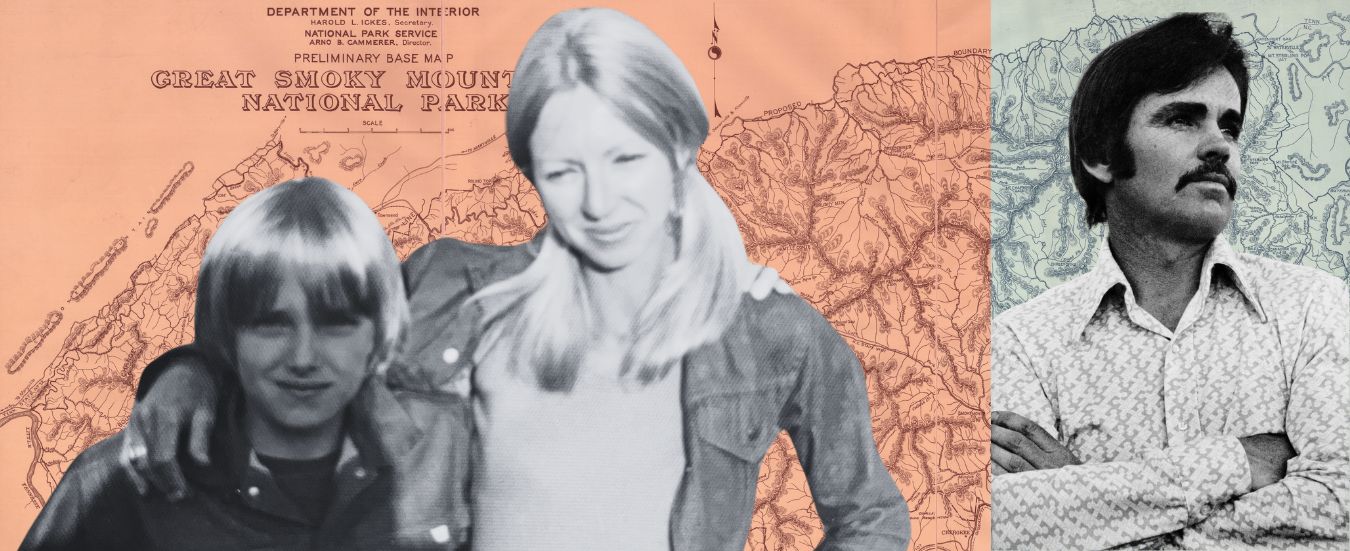

Perhaps this is where Clift’s autobiographical novel would have picked up: her escape from Kiama, first through modelling, then by enlisting in the army, where she wrote for the force’s publications. She met Johnston after the war at the offices of the Melbourne newspaper the Argus, where both were working. He was married with a young child, but they got together anyway. The affair resulted in Clift losing her job and Johnston quitting the paper in protest.

A few depressed years in London, two children and their first co-authored novel, High Valley (1949), followed. Then came Greece, and Clift’s travel memoirs. The family moved to the island of Kalymnos in 1954, seeking a way to write without compromise and without slipping into poverty. But from the first pages of Mermaid Singing (1956), outlining a jerky, perilous boat ride to the island – with the children drugged out on Dramamine – it’s clear that this will not be a story of freedom found, but of freedom annexed and recalibrated. Clift is fascinated with her new home of retsina and funeral pudding and lives dictated by necessity. But what the memoir is really fixated on is the baroque balancing act between pleasure and responsibility. How to write and look after children, and manage a house, and eat well, and clean up after yourself, and drink with friends, even go for a swim?

“A housewife is a housewife wherever she is — in the biggest city of the world or on a small Greek island. There is no escape. She must move always to the dreary recurring decimal of her rites,” she writes in Peel Me a Lotus (1959), her similar but slightly less bemused sequel, chronicling the family’s time on Hydra from February to October 1956. On their new island home the expats are everywhere, the summer is stinky and teeming with tourists, droughts and drainage problems persist and a film crew is spoiling the island’s idyll. Clift has just had a baby, her last, a boy named Jason. Hydra is where, in 1960, Clift and Johnston would befriend Leonard Cohen. “They drank more than other people, they wrote more, they got sick more, they got well more, they cursed more and they blessed more, and they helped a great deal more,” Cohen said about the couple. On the menus at his old haunt, Xeri Elia, there’s still a photo of the singer playing his guitar under the taverna’s tree, with a few friends surrounding him. Clift leans on his left side, mouth slightly open, eyes glassy.

The couple lived on Hydra for nine years before they were worn out by their self-imposed exile. Clift was hesitant to leave, but Johnston was eager – by then My Brother Jack had already been canonized, and he returned to Australia a celebrated author. Meanwhile, Clift was tasked with writing for a regular paycheck. She had written her memoirs and a couple of novels at this point, but her weekly column for the Sydney Morning Herald is what would make her beloved in her home country. In the women’s pages, sandwiched between advertisements for wiglets and gastric ulcer tablets, Clift wrote about returning to Sydney as a “home-grown migrant” in the 1960s, with wonderment and dark, knowing laughter. She is thrilled by cultural change and fanged political action, less so by the country’s remaining inwardness and latent conservatism. (One shudders with recognition coming to these columns now.) There are plenty of those Clift lists – funny dissections of address books, a catalogue of items cluttering her mantelpiece. Her allegiances are always and only to the young, the marginal; those outside and misunderstood. “We can’t win, of course,” she writes in a piece about those giving up careerist comforts and going it alone. “But there is a certain grim little pleasure in the fact of holding out, and, who knows? one of us – or even some of us – might score a bit.”

The suicide of a writer often leaves the living scrambling for a narrative explanation – a deathwish spurred by a husband’s humiliation, the anguish she felt as she struggled to write her autobiographical novel, with a protagonist now seemingly second-hand and used up. In the latter Charmian Clift’s perpetual looping around to youth, to Kiama, is rendered a symptom. Is it so simple? She had spent so many years in the pursuit of freedom, pinning it to people or places, often to be scalded in the aftermath. In the dreamy expanse of childhood she could finally tend to her own myths – no one else’s.

Isabella Trimboli is a writer based in Melbourne. Her criticism and essays have appeared in the Nation, the Los Angeles Review of Books and New Left Review, among others. She is working on a book of essays exploring female doubling and imitation in art

The post From sunshine to darkness appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-14 02:17:55 | Updated at 2024-11-21 18:19:17

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-14 02:17:55 | Updated at 2024-11-21 18:19:17

1 week ago