“Manchester is the south of the north”, writes Jeanette Winterson: spot-on. I’ve never met anyone who has a clear mental map of the place. On the ground it seems to have a grid pattern, but the roads splay out and there’s a strange bend in the middle. If you assume right angles, you end up round the back of somewhere else. The Northern Quarter” is more east than north. The railway from the north brings you round to Oxford Road station in the south, while trains from the south terminate at Piccadilly in the east, next to the Northern Quarter. The real northern quarter is in Salford, over the River Irwell (if you can find the river).

Manchester’s history also offers an illusory grid pattern. There’s a master narrative of progress, cantilevered by poverty and protest, but it doesn’t map onto reality, nor does it help you navigate far. Made in Manchester retells that story in sixteen breezy chapters. Here it is in sixteen sentences.

Roman Mamucium (or Mancunium) turned into medieval Manchester, a centre of the cloth trade. It rebelled against the crown in the civil wars, but thereafter knuckled down to commerce. The cotton industry kick-started the Industrial Revolution – the big bang that places Manchester at the origin point of the modern world. The stresses of progress generated riots, radicalism and liberalism, but all that was basically modern too. The shock city of the 1840s exposed the human problems of industrialization, but problems mean reform and reform means progress. Manchester has always drawn in migrants of all kinds, and nearly a third of its present-day population has been born abroad – yet another kind of progress. Thanks to all that progress Manchester became a big centre of engineering, technology and science. Being productive, it also produced a lot of literature and art. Manchester boomed even more in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, when it became a proper city with a civic infrastructure and big shops. Being so good at progress, Manchester led the campaign for votes for women. All that energy generated shedloads of popular culture, mainly because people wanted to get out of the place (or pretended to). The First World War brought more boom and bust, and in the Second World War the city was wrecked, but Mancunians were used to getting wrecked. Manchester has always been big on sport – really big. Thanks to postwar redevelopment, Manchester bottomed out in the 1970s and 1980s, but thanks to an IRA bomb it then went from northern poorhouse to northern powerhouse. If there’s one thing bigger than sport in Manchester, it’s music. In the twenty-first century it’s more of the same, only more so: forwards in all directions.

On this reading, if socialism is what Labour governments do, then progress is what Manchester does. Until incorporation in 1838, however, it was (as Daniel Defoe once had it) “the greatest mere village in England”, governed by high Tory parish and manorial authorities with an improvement commission acting as a development corporation. The centre of local government was the twin town of Salford, which housed the coercive infrastructure of law courts, workhouse and prison. Manchester remained a law unto itself. Freed of any corporate regulation, it was free-market long before the famous “Manchester school” liberalism got going. The resulting waves of protest have since been incorporated as a core element of Manchester’s heritage, as exemplified in the bicentenary of the “Peterloo massacre” of pro-democracy protesters (1819). It is home to the People’s History Museum, which has a new strapline (slightly worrying in view of the abysmal voter turnout in some wards): “the national museum of democracy”.

Greater Manchester today is a city region of nearly three million people, and Manchester is one borough among ten. (The prototype name was SELNEC – South East Lancashire and North East Cheshire.) The city is a Labour one-party state with more than its share of both money and deprivation (not to mention the highly profitable airport), but is not so historically dominant of its region as is often imagined. The boroughs in the north – Salford, Wigan, Bolton, Bury – still feel more Lancashire than Manchester, and occasionally vote Tory. The Pennine regions to the east feel more Yorkshire (ask the inhabitants of grafted-on Saddleworth), while the Porsche-pestered southern parts, formerly in affluent Cheshire, feel – well, southern.

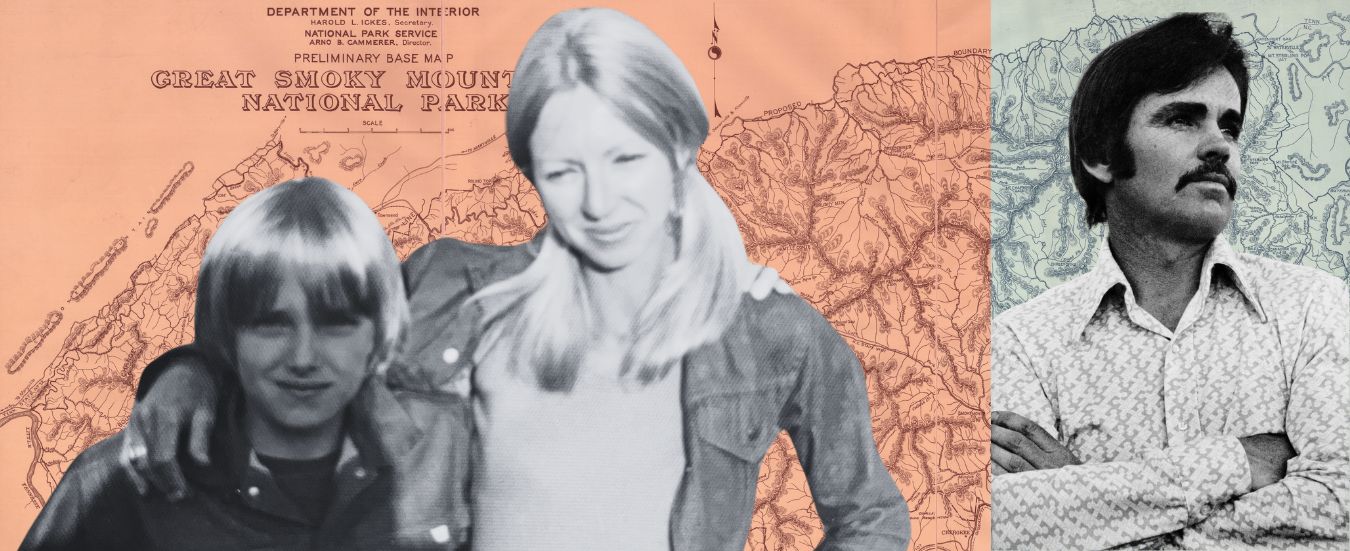

Made in Manchester is described by its publishers as “of unrivalled authority and breadth”, but its main source is other histories of Manchester. Many of the sporting and cultural celebrities listed are from outside Manchester, as is much of the history. Place names are sprayed around, but since the book lacks maps and illustrations, it tends to reinforce the common impression that the entire region is one bricked-over cotton town. How else are outsiders expected to differentiate between Farnworth and Failsworth, or even Wigan or (trick question) Warrington?

Many of Brian Groom’s footnotes are to a book of themed essays edited by Alan Kidd and Terry Wyke, Manchester: Making the modern city (2016), which is weightier but no longer, and superbly illustrated. Those who relish a deeper sense of place will enjoy the history of Manchester and Salford contained in Paul Salveson’s Lancastrians (2023). One historical puzzle remains, however: why do all the best comedians come from Bolton?

Robert Poole is the author of Peterloo: The English uprising, 2019

The post Greater than the sum appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-20 16:49:32 | Updated at 2024-11-21 18:23:17

1 day ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-20 16:49:32 | Updated at 2024-11-21 18:23:17

1 day ago