One might have assumed that the political thought of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries would be occupied, in a significant way, with cities. Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Rousseau and other founders of modern political philosophy all equated the good state with the city-state. It seemed obvious to them that the best sort of life could be realized only within the confines of an urban political community. Today more than half us live in cities; by the end of the century it is likely to be upwards of 75 per cent. And over the past 150 years urbanization and its challenges have emerged as a central concern for sociologists and other social scientists.

Yet most political philosophers have shown little interest in this subject. (Theorists writing in the Marxist tradition, such as Henri Lefebvre, David Harvey or Mike Davis are the exceptions, but, like Marx himself, they write more as radical political economists than as political philosophers.) Why this neglect? The answer seems to rest on an unarticulated assumption that cities are just like nation states, so any principles that apply to these should also apply to cities. Only cities are smaller and less powerful, and therefore less interesting.

One of the merits of Jonathan Wolff and Avner de-Shalit’s new book is that it helps us see how mistaken this view is. As they point out, cities aren’t necessarily smaller than nations; many are much larger. (London and Paris are bigger, in terms of population, than many European states.) They produce a disproportionate share of the world’s wealth and more than their fair share of environmental harms. And city governments hold many of the levers that drive development, shape access to jobs, housing and public services, and generate patterns of spatial segregation.

As a result, the powers that city governments exercise are central to the lives of city dwellers. If you are a sex worker in the slums of Mumbai, sleeping rough in New York or ekeing out a living as a street vendor in Cairo or a waste picker in São Paulo, the politics and policies of your city administration are likely to be more influential than national government on your fate. Even the plutocrats of Fifth Avenue or Knightsbridge depend to no small extent on city government for the security of the streets, the scale and nature of local development, the quality of neighbourhood amenities and levels of congestion and air pollution.

But it’s not just that city governments are powerful. Cities pose distinct normative challenges: should city governments intervene in individual free choices to prevent residential segregation? Who should get priority in the use of scarce roads? Should cities be allowed their own migration policies?They also offer distinct ethical possibilities. The equality of the street, the freedom of the square, the communism of the park, the sociability of the carnival are uniquely urban.

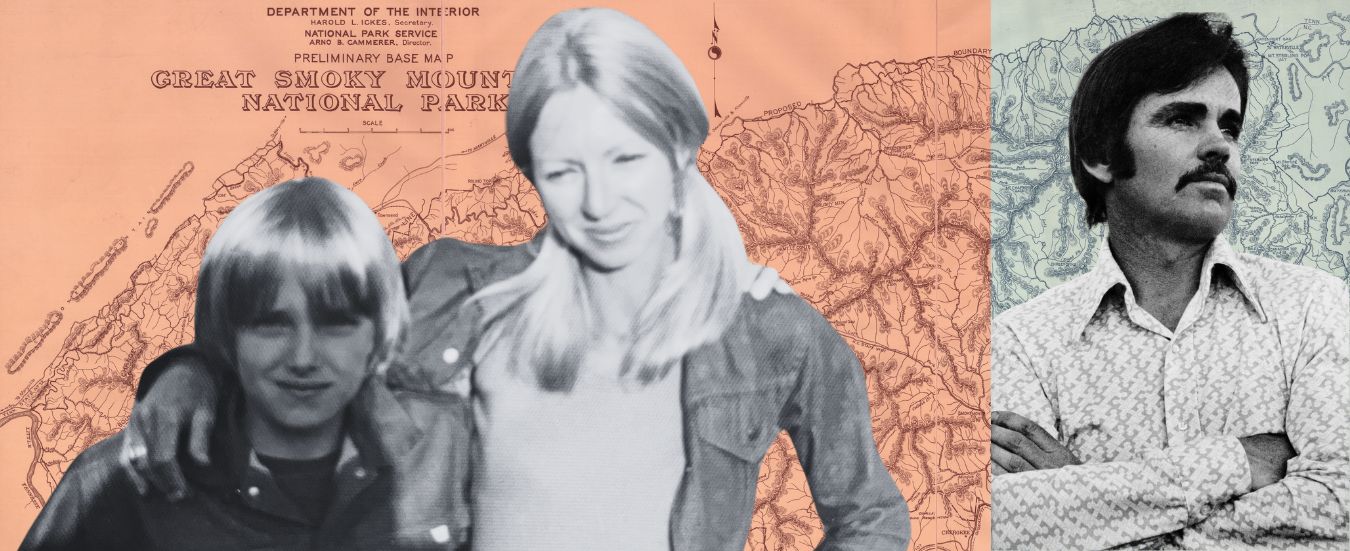

The authors are professors of political philosophy with a feel for city life. (Wolff lives in London, de-Shalit in Jerusalem). They have both written about cities and what they have christened “city-zens” (people who live and work in cities) before. They specialize in applied political philosophy and work closely with policymakers to help them conceptualize issues, articulate values and think through choices and trade-offs. They are also committed egalitarians, and the mission they set themselves here is to answer the question: what makes a city a city of equals?

They bring out the distinctive nature of urban equality by pursuing a paradoxical line of thought. Should governments set on lessening inequality focus on economic inequality as a priority? The answer for national governments is generally “yes”. Nation states have tight borders and only the most radical redistributive policies will see people leaving the country in large numbers. But city-zens can leave cities more easily. The surest way for a city government to narrow inequalities or wealth or income, then, is to encourage the poor or the rich to move out. This is more than a thought experiment. In the 1970s and 1980s many US cities saw the middle classes leave for suburbs. More recently, as gentrifiers have moved into city centres, many poorer residents have been squeezed out. These developments might narrow economic inequalities, but they feel like a loss to urban equity.

By contrast, cities such as San Francisco and Berkeley have become highly unequal in economic terms. Yet the super-wealthy and the poor and homeless live in close proximity and share streets and parks, in what Wolff and de-Shalit describe as a “spirit of equality”. No doubt it would be better if the wealth gap could be narrowed in these cities, but not if it involved either the rich or the poor moving out.

If economic equality is only one aspect of equality that egalitarians should value, what are the others? Wolff and de-Shalit set out to answer this in a distinctive way. They bring together their own philosophical reflections and extensive reading of research on cities with short conversations with more than 180 interlocutors in European, North and South American and Israeli cities, most of whom they encountered on city streets.

Where much political philosophy understands justice in terms of the advancement of political and civil rights, and the distribution of wealth and income, the account of urban equality that emerges from this research emphasizes the importance of spatial and social factors. When you ask ordinary city dwellers about inequality in their city, they don’t refer just to poor housing or low pay. They talk about the way in which people living in slums are cut off from the fabric of the city, or the way that less powerful and low-status groups are made to feel excluded from the life of the place. Put more positively, the authors argue that, in a city of equals, people have decent access to facilities, services and resources, and feel welcomed by city authorities and fellow citizens. They can walk through the city’s streets with their heads held high.

In line with their highly applied approach, Wolff and de-Shalit devote considerable space to exploring the sort of policies that could advance their account of urban equality, and the possible synergies and tensions between them. The final chapter sets out how their analysis could be used to help municipal government understand what inequality looks like in their city and how to make it fairer.

City of Equals is an acute and valuable work, but it is almost too modest in its ambitions. No doubt a conceptual framework that enables cities to think more clearly about equality can be helpful. But I can’t help feeling that a less academic version of this book would reach a wider audience of policymakers.

More fundamentally, given how little attention has been paid by philosophers to cities, some more foundational work would be welcome. Wolff and de-Shalit have little to say about why they have decided to focus on equality – other than that they believe in it – or where other values fit in. Is this a theory of urban justice or just of urban equality? (They can be, but are not necessarily, the same things). How does urban equality, as the authors understand it, relate to ideals of liberty, democracy, citizenship and the public realm that were long so central to philosophical thinking about cities, and are still so central to urban life? And how should we weigh the claims of national and city governments?

Jonathan Wolff and Avner de-Shalit might fairly bridle at being criticized for neglecting questions that they never set out to address. But we need work that tackles questions such as these if we are to persuade more philosophers to take cities seriously.

Ben Rogers is Professor of Practice – London, University of London and Bloomberg Distinguished Fellow, LSE Cities, London School of Economics. He was founding Director of Centre for London, 2011–21

The post Holding heads high appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-20 16:49:31 | Updated at 2024-11-21 19:10:03

1 day ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-20 16:49:31 | Updated at 2024-11-21 19:10:03

1 day ago