“Thank you, Zecharias, have a good day,” Desta told me at the end of our first video chat, catching me off guard.

I didn’t know what to say – you can’t respond in kind when the person on the other end of the line is under fed, suffering from heat stroke and sitting in a crowded, disease infested migrant prison facility that he says smells of sewage.

Desta was among tens of thousands of Ethiopian migrants who, in 2020, were imprisoned in Saudi Arabia and kept for up to a year in woeful conditions unbecoming of an oil-rich Gulf state.

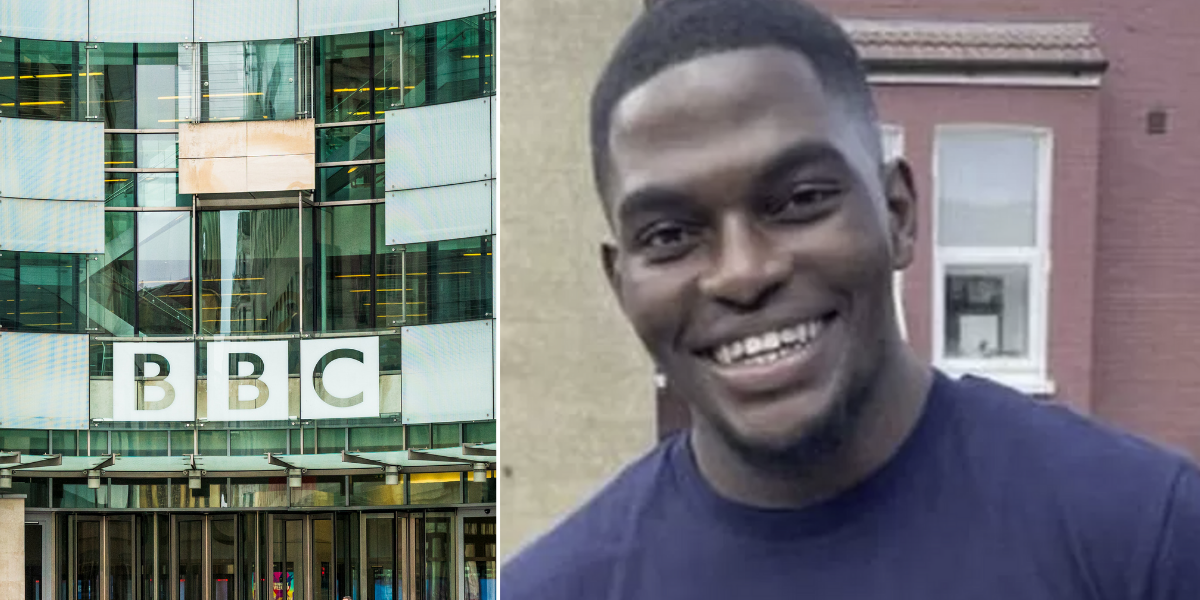

I reached him using phones smuggled into the prisons to establish contact with detainees and confirm accounts of mistreatment for an investigation I was working on for The Telegraph’s Global Health Security team.

At the end of our conversations I’d wave goodbye to Desta through my webcam, then spend the next half hour looking at my notes or sifting through blurry screenshots.

Being of Ethiopian descent and able to speak the same language as many of the detainees, it was especially gut-wrenching to learn and witness their terrible predicament.

One man told me he used to work as a labourer at the bustling Mexico district in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, about fifteen minutes from where I went to secondary school.

Once, a desperate teenager with a horrible rash came on screen to ask if I was a UN migration agency worker who could get him home quickly. He broke down in tears when I clarified who I was, disappearing from view.

Speaking to Desta and the other detainees would leave me riddled with guilt about the food I ate or the warm bed I was able to sleep in.

On some days I’d put away my laptop and pour myself a drink.

After hundreds of hours of investigative work with my colleague and good friend Will Brown, and dozens of conversations with Desta and many other inmates, The Daily Telegraph published the first of eight stories cataloguing the horrors inside the detention facilities, including photographs and videos showing the emaciated detainees.

The outrage was beyond anything we had anticipated. The stories quickly went viral on social media and were covered, cited or reprinted around the world.

Will and I spent weeks accommodating media requests to discuss our findings on radio programs and in newspaper interviews.

There was considerable outcry in Ethiopia, as among our findings was the revelation that Ethiopian officials had known about the suffering of their citizens in the Kingdom for months and had attempted to cover it up.

Our investigation – combined with a thorough, detailed report prepared by Nadia Hardman, an amazing researcher at Human Rights Watch – led to an EU Parliament resolution condemning Saudi Arabia’s treatment of migrants in its prisons.

Eventually, a repatriation agreement to fly migrants home was reached in January 2021. Over 30,000 migrants returned home by July 2021.

But four years on, large numbers of people remain incarcerated in Saudi detention facilities – many of them Ethiopian refugees who fled conflict in their home country.

On top of that, hundreds – possibly thousands – of Ethiopians have been massacred by Saudi border guards while trying to reach the Kingdom from Yemen, according to a HRW investigation.

And yet, Saudi Arabia is on course to become the centre of the football world.

In stark contrast to its treatment of African refugees, African footballing stars, including former Chelsea star and the world’s best goalkeeper of 2021 Edouard Mendy, and Liverpool legend Sadio Mane, are paid millions to ply their trade in the Saudi Pro League, joining dozens of other football stars including Portugal’s Cristiano Ronaldo.

And in a matter of weeks Saudi Arabia is set to be named host of the 2034 World Cup.

It is sportswashing, and it is working. Credible reports of the heinous and systemic, xenophobic violence by Saudi authorities hardly stir outrage anymore.

A year or so after our first article was published, the Saudi Public Investment Fund completed its purchase of Newcastle United – a move personally overseen by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, according to a report in The Telegraph.

It hardly bothered Newcastle fans, who took to the streets to celebrate the takeover.

In Ethiopia meanwhile, there are entire regions where you’d be hard pressed to find someone who doesn’t know someone who has passed through the Saudi migrant prison system, or ended up in a mass grave on the Saudi-Yemeni border.

The sportswashing initiative has achieved its aim. Four years after our investigation caused global outcry and prompted a pledge from Riyadh to take action, the plight of the victims of Saudi Arabia’s human rights abuses – like those held in its detention centres – is fading from view.

The allure of the beautiful game is simply too great.

Read more: Tens of thousands suffer in Saudi detention centres despite promise of reform

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

By The Telegraph (World News) | Created at 2024-10-29 18:11:43 | Updated at 2024-11-05 08:10:18

1 week ago

By The Telegraph (World News) | Created at 2024-10-29 18:11:43 | Updated at 2024-11-05 08:10:18

1 week ago