Here’s a confession: I do not feel particularly disturbed when great American institutions come under scrutiny, whether they be Harvard, the NSA, Wall Street, or the CDC. I figure if they are under attack it is probably for good reason, and either way will be made more honest by weathering the storm of outrage directed at them.

That is, until the only institution I feel any great affinity toward, and possibly the only thing I can claim any expertise in, was called into question last week. I’m talking of course of the Great American Sleepover.

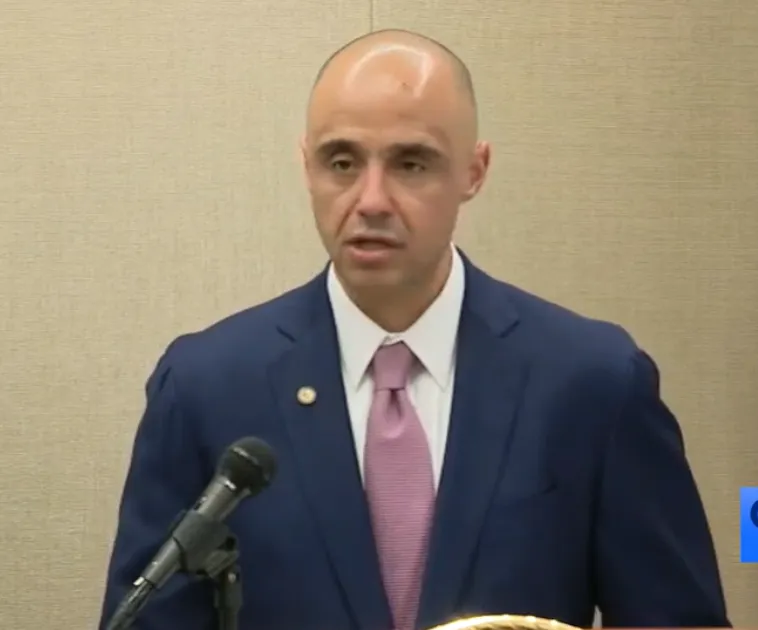

Over the holidays, the technologist Sriram Krishnan was named as Trump’s AI advisor. Off of that, a battle over H-1B visas bubbled up, triggering a civil war in MAGA Land—where many say immigrants like Krishnan should not be prioritized over native-born citizens. That led to future DOGE co-chief Vivek Ramaswamy, whose parents were born in India, to take a swipe at American culture:

“A culture that celebrates the prom queen over the math olympiad champ, or the jock over the valedictorian, will not produce the best engineers,” he wrote on X. He went on to recommend a different upbringing for America’s kids: “More movies like Whiplash, fewer reruns of “Friends.” More math tutoring, fewer sleepovers.”

Fewer sleepovers is a position echoed by Amy Chua in her book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, part memoir, part ode to the intense and demanding parenting style of immigrants. “Attend a sleepover,” she writes, was the first bullet in a list of “things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do.” How else might they become “math whizzes and music prodigies”?

To which I say: Hold the corded kitchen phone. Okay, now put your mom on so she can talk to my mom about whose house we’re sleeping at.

Sleeping over, like crushes and the Homecoming game, is a cornerstone of American childhood, or at least it was of my own. I estimate I’ve had hundreds of them.

At Julia’s house, her mom sang the long version of “American Pie” to us before bed (she had a beautiful voice). She also would make me eat spinach and drink milk at dinner: two things that never happened at my own house, where activities included eavesdropping on my older sisters until one of them chased us down the hall. Michelle’s had an ancient Playstation in their guest room where we’d play Mario Kart, and then stare at the pictures in a book about what happens at puberty—The Care & Keeping of You, put out by American Girl—with horror and fascination. I can tell you right now which girls in my fifth-grade class had TVs in their rooms, en suite bathrooms, or trundle beds; having all three being the today equivalent of having your own plane.

At sleepovers, you came face to face with many versions of the American dream, or at least many versions of American snacks. You learned that different families had different cultures, and different rules, and you learned how to be a guest, and how to exist outside the sphere of your own family. It’s like a laboratory to see if your parents’ rearing, at least with regard to manners and to self-soothing, worked.

Delirious and giddy—two common sleepover symptoms—at the Weinbergers during an epic group sleepover, I went to the fridge, took out a can of whipped cream, and dispensed it into my own mouth. The look of disgust on the face of my friend’s grandfather, who was sitting 10 feet away at the dining room table, still brings feelings of shame up in me. I learned exactly how not to act, not just at someone else’s house, but really, ever, at that moment.

There were sleepovers at my house too. In fact there was a standing doubleheader—that’s Friday and Saturday night sleepovers, one after the other— with my three best girlfriends all throughout seventh grade. We choked back giggles when we heard the heavy footsteps of my dad approaching the TV room, where we’d burrowed into every pillow and comforter in the house. “Girls!” Inhale. “Do you have any idea what time it is?”

Rather than just ruining all the fun, parents today seem more upset that their children might be exposed to fun at all, at least in the cases of Vivek and Chua. But even not being invited to a sleepover can be a lesson in the brutal facts of life. Hearing the crushing refrain that “there’s not enough room in the basement” or that I couldn’t be there since the plan was to watch a PG-13 movie—something I wasn’t allowed to do until I was 13—cut like a knife. But I like to think it made me more resilient when dealing with rejection.

Sleepovers in high school brought marathon Skype calls with boys, some of them strangers we found on the internet through Chatroulette or Omegle, as well as runs for fast food in someone’s mom’s van. This behavior—conference calls with strangers, some of whom were perverts—is not a parent’s dream scenario, but it was also inevitable. We were going to experiment with and on the internet. Wasn’t it better to do it with a friend?

All of this was good preparation for college, which is like if a sleepover freebased cocaine. There were the freshman dorms, of course, but I was also in a sorority, which functions like a slutty orphanage. It was the Sleepover Super Bowl. Everyone had a roommate and there were 30 rooms; hundreds of pillows to drop your head sideways onto and talk on; 65 closets—thousands of garments to dress up in and then hide when someone inevitably broke a clasp. There was always someone awake, blushing into their phone waiting to be asked about the guy. Nirvana, I tell you.

Kids show up to college today never having fostered intimacy with another person. When friendships are mediated by screen there is no opportunity to get into the nitty-gritty. Learning how to shave your legs, how to do your hair, how to use a tampon, or in my case learning that your eyebrows need an overhaul are all things that happen at sleepovers. But it wasn’t just about going to war with our own body hair; it was the crucible where girls grow up.

Even today, despite the hardening, with age, of everyone’s schedules and skincare routines and bed rituals, I’ll often sleep out. There’s something special, even when you’re grown up, about forgoing a fancy dinner reservation and instead staying in and waking up in the same place as your best friend.

But sleepovers are threatened, and not just by parents anxious about their kids getting enough sleep before a debate tournament or studying enough vocabulary words to ace the SAT. There are parents who forgo sleepovers for safetyist reasons—they’re afraid their kid might get molested or traumatized at someone else’s house. Forget the fact that kids are most likely to be abused in their own home. Some families are opting for the safer and more civilized “sleep under” where kids get dressed in their PJs and watch a movie—supervised, I’m sure—only for everyone to be picked up before bedtime. You might as well piss on them and tell them it’s raining.

The pushback against sleepovers at this moment is understandable. A sleepover is a minefield. People are paranoid and they don’t want their parenting undone or challenged. They don’t want their child to face the terror of homesickness, alone, in the middle of the night, in someone else’s darkened house. Or to be made fun of or excluded or forced to negotiate with a preteen bully—the most fearsome kind—over who has to sleep on the floor. Or to tell some other adult that actually they’re allergic to peanut butter, or that it’s time to take their medicine. Parents don’t want their kids coming home cranky or revved up. And they don’t want their own parenting judged if their kid is rude or out of control.

To which I say: That’s the whole point.

Was my brain made mealier because I had at least one sleepover every weekend for a decade? It’s very possible. Could I have read more of the Western Canon, or gotten better at piano had I not routinely gone to sleep in the early morning during peak brain development? Sure. Would I have been spared some traumatic experiences, like being told, in front of an audience at 12, that it was past time I’d started wearing a bra? Definitely.

But I don’t regret a single sleepover I’ve had. My best memories are from those nights—when someone else’s family dinner would devolve into watching movies would devolve into a late-night snack would devolve into a game of truth or dare would devolve into hysterics would devolve into trading secrets and dreams and forging a bond, crucially, outside of the sight line of teachers or parents or any other adult. And doesn’t that mark the beginning of becoming your own person?

To the leaders of this country who want to take away sleepovers, I double dog dare you: Come and take them.

By The Free Press | Created at 2024-12-29 16:06:39 | Updated at 2025-01-01 14:08:59

2 days ago

By The Free Press | Created at 2024-12-29 16:06:39 | Updated at 2025-01-01 14:08:59

2 days ago