Should we be teaching contemporary literature in schools? If so, how? Asked to address the question for a gathering of Italian English lit teachers, I found myself remembering, not for the first time, Edwin Muir’s lines: “Into thirty centuries born, / At home in them all but the very last”. We feel we know the past, from Homer’s Troy to Joyce’s Dublin. “There the fallen are up again”, says Muir, “in mortality’s second day.” We’re familiar with the protagonists: the Wife of Bath, Hamlet, Gulliver, Elizabeth Bennet, Jane Eyre, Mr Micawber, Tess, Stephen Dedalus, Mrs Dalloway, Lady Chatterley. We can put the whole procession in order, see the development from one to the next. We can teach them confidently. But the present is disorientating. “To-morrow and to-morrow brings / Endless beginnings without end.”

Certainly, there are endless books being written. Worldwide, more than 100,000 novels are published in English each year. Even the prize-winners run into scores. So the first challenge is which authors to teach – the celebrities, those who sold most? – and the second what to say about them. “Here, if we could recognize it”, wrote Virginia Woolf. contemplating new titles in a bookshop, “lies some poem, or novel, or history which will stand up and speak with other ages about our age when we lie prone and silent…”. But it was “oddly difficult”, she continued, to say “which are the real books and what it is that they are telling us, and which are the stuffed books which will come to pieces when they have lain about for a year or two”.

So, if we teach contemporary literature, we must do so with the sobering awareness that we may well be teaching also-rans. Any number of authors as celebrated in their day as Salman Rushdie or Zadie Smith are today have long been forgotten. Who was reputed “the most published man of the nineteenth century” and “the most popular writer of his time”? Not Dickens, but G. M. W. Reynolds. Hardly a household name.

The problem is exacerbated by politics. In 1855 Woolf’s uncle James Fitzjames Stephen lamented “the habit, which of late years has become so common, of using novels to ventilate opinions” and to indulge in “social or political argumenta ad misericordiam”. Dickens was the main culprit. Not that he wasn’t a genius, but his popularity depended largely on the “spirit of revolt against all established rules which pervades every one of his books … an exquisite adaptation of his own turn of mind to the peculiar state of feeling which … prevails in some classes”.

How much of a contemporary author’s celebrity has to do with their alignment with the zeitgeist? With identity politics, ethnicity, gender? It is hard not to sympathize with those teachers, the vast majority in Italy, who choose to wrap things up before the Second World War or to have the story end over a Victory Gin with Winston Smith. On the other hand, if we give the impression that literature is a thing of the past, deprived of contemporary relevance, our subject is dead.

Turn the problem on its head. That’s the only solution I can see. From day one. Prepare students for the chaos of the contemporary by reminding them it was ever thus. It was never clear which were the real books and which the stuffed. Debate was always fierce. It was not a compliment to call Donne and company “the metaphysicals”. It was an insult. They “were men of learning, and to show their learning was their whole endeavor”. Thus Samuel Johnson. Invite students to take a position. “Swift’s writings endeavour to debase the human”, Samuel Richardson complained. “Descriptions that shock our delicacy cannot have the least good effect upon our minds”, agreed John Boyle, perhaps remembering the Yahoos “discharging their excrements” on Gulliver’s head. Was he altogether wrong? When we leave aside the SparkNotes and the clever patterning of imagery and symbolism, and put ourselves in relation to the writing, then the past itself becomes contemporary. “Do you support [Tess] or not?” The Duchess of Abercorn would ask of her dinner guests. If they thought she was a “little harlot”, she sat them at one table. If they felt she was a “poor wronged innocent”, they joined the duchess herself at another. “De te, fabula”, Browning insisted at the end of the gloomy story that is “The Statue and the Bust”. Where do you stand?

In short, let’s be a little less at home with the past. If Kipling is now largely cancelled and the Royal Shakespeare is warning audiences to wince at fat-shaming in The Merry Wives of Windsor, perhaps it was never stable anyway. (“Is it fantasy or faith”, Muir wondered, “That keeps intact that marvellous show?”) With this approach, by the time we present our contemporaries, students should be aware of the difficulty of distinguishing the aesthetic from the political, religious and ideological. Teaching literature is not a question of analysing consecrated masterpieces, but of savouring the challenge of this or that representation of the world, and recognizing that we are part of the fray. You too, Muir warns, “shall walk the Trojan streets / When home are sailed the murdering fleets”. A kid needs to get his/her/their bearings.

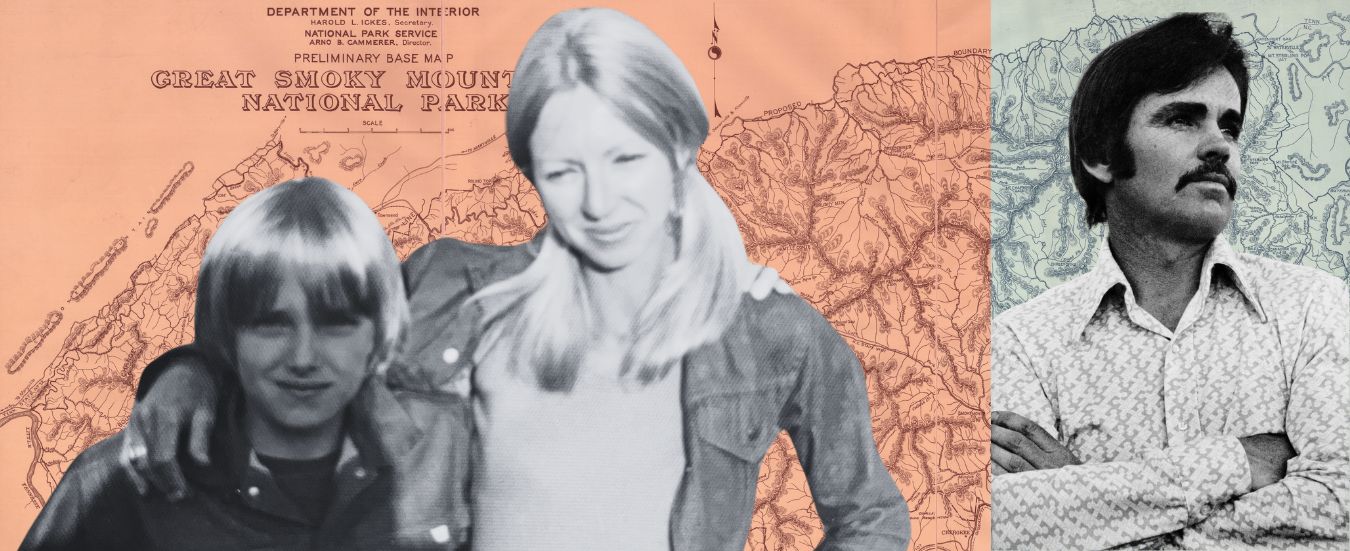

Tim Parks’s most recent novel, Mr Geography, appeared in August

The post In the fray appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-14 02:17:55 | Updated at 2024-11-21 18:28:50

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-14 02:17:55 | Updated at 2024-11-21 18:28:50

1 week ago