For citation, please use:

Kapoor, N., 2024. India’s South Asia Policy Revisited: A Role for Russia. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(4), pp. 82–104. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-4-82-104

The term ‘South Asian subcontinent’ encompasses India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, the Maldives, and Afghanistan. (Together, these form the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).) On the basis of historical legacies, India has long considered itself the leading power in South Asia. However, notwithstanding its economic success, India has not reached the status of regional hegemon and has never been able to dominate the entire subcontinent. In recent years, India’s ambitions in South Asia have been seriously challenged by China, which has strengthened its economic, military, and political position there.

Seeking to constrain external powers’ increasing presence in the immediate neighborhood, New Delhi has embraced the role of friendly non-regional actors in the region. This policy shift stems from awareness of its limited capacity as a developing country and of its inability to unilaterally impose its will on the region

These trends have become increasingly important for Russia as it seeks to develop its relations with the rest of the world, following their breakdown with the West. India remains one of the key powers determining the balance in South Asia, and its shift in approach is already affecting the policies of other stakeholders. New Delhi also remains Moscow’s key partner in the subcontinent, as Russia’s relations with other South Asian powers are limited. Therefore, the shifts in Indian policy will be used to highlight the evolving trends in South Asia, which will help evaluate the opportunities and challenges for Russia therein. Building closer economic ties with South Asia is crucial for Russia, given its limited resources and numerous challenges. Moscow’s non-coherent policy towards South Asia must be overhauled to support Russia’s pivot to the East and position in the Indian Ocean.

This study also highlights the Global South’s heterogeneity, underlying the necessity of a careful policy regarding it.

Russia in South Asia

Although Russia enjoys a “special and privileged strategic partnership” with India as the leading South Asian power, Moscow does not have a “comprehensive” strategy towards the subcontinent (Topychkanov, 2017). In the aftermath of the USSR’s collapse, Russia was not in a position to maintain extensive relationships with smaller South Asian states, and it was focused on other regions considered to be of greater, “existential” importance (Korolev, 2023). Like the U.S., it sought to prevent nuclear confrontation on the subcontinent and to contain the threat of Islamic extremism (Bajpai, 2021). Beyond that, its regional policy has been piecemeal and focused on India (Bakshi, 1999).

Russia is one of India’s leading arms suppliers, although its share has declined recently. Conversely, energy cooperation has grown since 2022, with India importing record volumes of oil at discounted rates and pushing bilateral trade over the $60 billion mark for the first time since the Cold War. However, the growing economic cooperation faces challenges: the threat of secondary sanctions, imperfect connectivity, trade imbalance, and payment difficulties. Although China has emerged as Russia’s key partner in recent years, Moscow has ensured its own neutrality on issues that involve both China and India.

India has similarly wished to avoid alienating Russia, lest Russia seek even closer ties with China.

Russia has been careful about how it engages with Pakistan, given the Indian sensitivities involved. So far, there has only been limited cooperation between the two countries, and apart from limited arms sales and joint military exercises, there has not been a perceptible shift in economic or strategic engagement. Between 2000 and 2023, Russia supplied Pakistan with arms worth $692 million, as per SIPRI estimates, constituting 3.2% of all exports to Pakistan. In contrast, the exports to India were worth $37.9 billion, which comes to 63% of all exports to India. Although Russia’s deference to India’s concerns can lead to negative Pakistani perceptions of Russian actions as “unpredictable” (Topychkanov, 2017), Moscow has so far been unwilling to antagonize New Delhi in pursuit of strengthened relations with Islamabad. Pakistan’s economic and political instability contributes to Russian concerns about its reliability as a partner (Ivashentsov, 2019); hence, the relationship has remained focused on specific issues like Afghanistan.

Russia has increased high-level interaction with Pakistani officials in the last couple of years (Zakharov, 2024a). 2023 saw the first contract by a private Pakistani refining company for the import of Russian oil, and Pakistan is considering increasing those imports despite difficulties with payments, pricing, delivery, etc. (TASS, 2023; RIA Novosti, 2023). Islamabad imported 800,000 tons of wheat from Russia in 2023 (Izvestiya, 2023). In July 2023–March 2024, Pakistan imported 2.1m tons of Russian wheat (5% of Russia’s wheat exports), becoming Russia’s fourth-largest customer (TASS, 2024a).

Russia has taken account of Islamabad’s strong influence in Kabul. It forms part of both the Extended “Troika” on Peaceful Settlement in Afghanistan and the Moscow Format of Consultations on Afghanistan. The exclusion of India from meetings of the Extended “Troika” convened by Russia invited a sharp response (Laskar, 2021), highlighting the careful diplomacy that Moscow has had to practice in this domain.

Although India began a careful outreach to the Taliban, with the first public engagement in 2021 in Doha followed by a humanitarian aid campaign (Sareen, 2022), it does not have significant influence with the current leadership of Afghanistan. Meanwhile Russia, seeking to prevent violence spilling into Central Asia and beyond, has continued its engagement with Pakistan on Afghanistan (Kapoor, 2021). It cites drug trafficking, ISIS, and arms smuggling as necessitating its engagement with the Taliban (Stepanova, 2018). Apart from managing the security situation, Russia sees its role in Afghanistan as part of its status as a key Eurasian power, especially after the withdrawal of U.S. forces (Bordachev, 2021). It has hosted the Moscow Format of Consultations on Afghanistan (involving Russia, Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, Iran, India, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan) since 2017.

Russia’s relations with Bangladesh have a cordial history dating back to the latter’s independence in 1971, but the first visit by a Russian foreign minister since then took place only in 2023 with a working visit by Sergei Lavrov. In 2017-2021, Russia was the second-largest supplier of arms to Bangladesh (at 9.2%) but dropped out of this position and has not regained it since (SIPRI, 2022). Although post-Soviet relations have not been close, some economic and military contacts have been maintained. The Pacific Fleet’s 2023 visit to Bangladesh, the first ever, signaled an attempt to renew military diplomacy between the two countries (Zakharov, 2024b). The key bilateral achievement is the Rooppur nuclear power plant, currently under construction. Additionally, Gazprom is negotiating drilling five onshore wells on Bhola Island in the Shahbazpur, Bhola North and Shahbazpur Northeast fields. These fields have a combined capacity of 2.8 Tcf, while Bangladesh’s remaining gas reserve (proven + probable) stands at 9.57 Tcf (Energy Scenario of Bangladesh, 2024). Since 2012, Gazprom has drilled 17 gas wells in Bangladesh (The Financial Express, 2022b). However, aside from rising agricultural exports from Russia, bilateral trade has remained limited, reaching $2.7 billion in 2023 (Sputnik India, 2024). It now also faces additional challenges due to Dhaka’s compliance with Western sanctions, which have complicated the efforts of the EAEU-Bangladesh joint working group to enhance trade (The Financial Express, 2023).

Russia’s relations with Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Nepal have remained cordial but limited. While presidential visits to Moscow from Sri Lanka happened only in 2010 (a working visit) and 2017 (an official visit), the foreign ministries maintain regular contact (MID, 2022). The foreign ministers of both countries have emphasized their interest in maintaining regular contact (MID, 2024), which also includes regular inter-parliamentary exchanges, meetings between defense and law enforcement agencies, as well as people-to-people contact (MID, 2022). Trade remains limited, having touched $373 million in 2021, with discussions for future cooperation revolving around nuclear energy (Gubin, 2022), supply of coal and petroleum products, cooperation in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries, and hydropower.

In 2019, a working visit by Maldivian Foreign Minister Abdulla Shahid to Russia led to the establishment of visa-free travel for Russians, and the country received its highest number of tourists from Russia in 2023 after a dip in 2022 (Forbes, 2024). After 2022, the Maldives became a conduit for Russian import of U.S.-made semiconductors, although this eventually led to U.S. sanctions (U.S. Department of Treasury, 2023). In 2024, the Russian government announced plans to open a consulate in the capital city Male.

Thus, Russia’s engagement in South Asia is marked by three factors: India’s position as its key partner, Afghanistan’s importance, and cordial but limited relations with the rest of the subcontinent. In view of Russia’s limited capacity in South Asia and the intensely competitive environment there, some Russian experts have called for Russia to follow a “kind of non-alignment policy in South Asia” (Ivashentsov, 2019), avoiding entanglement in regional affairs and promoting the peaceful resolution of disputes. This is considered important in the context of the escalating U.S.-China rivalry and the need for Russia to be seen as a neutral player in Asia (Valdai Discussion Club, 2023).

That remains a good rule of thumb but needs to be supplemented by specific policy measures. Given the breakdown of the Western vector of its foreign policy, Russia must enhance its presence throughout the East, and South Asia can better link it to the Indian Ocean.

Also, focusing on specific regions in the East can help Russia avoid the pitfalls of policy making based on broad categories like ‘the Rest’ or the ‘Global South.’

It is in this context that India’s policy shift in South Asia—inviting the cooperation of non-regional powers—becomes relevant to Russia.

India and China

China’s steadily increasing presence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region—diplomatic, strategic, and economic (Bajpai, 2021)—and rising tensions with it have fed a “sense of encirclement” in India (Smith, 2020).

Indian concerns about China’s growing military power (Joshi and Mukherjee, 2020) have been exacerbated by the latter’s drift away from previous understandings about the “peaceful handling of disputes” (Gokhale, 2021) and by increasing border clashes since 2008, with the 2020 Galwan Valley clashes marking a turning point. India is also increasingly wary of China in the Indian Ocean. China, conversely, resents India’s opposition to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its support of “free, open, inclusive, peaceful, and prosperous Indo-Pacific” (Jaishankar, 2022) that includes cooperation with the U.S. in the region and Quad (which China perceives as directed against itself), contributing to rising mistrust on both sides (Gokhale, 2021).

And while India’s recent economic growth allows it to respond to China’s moves in its neighborhood, the latter are far greater in scale.

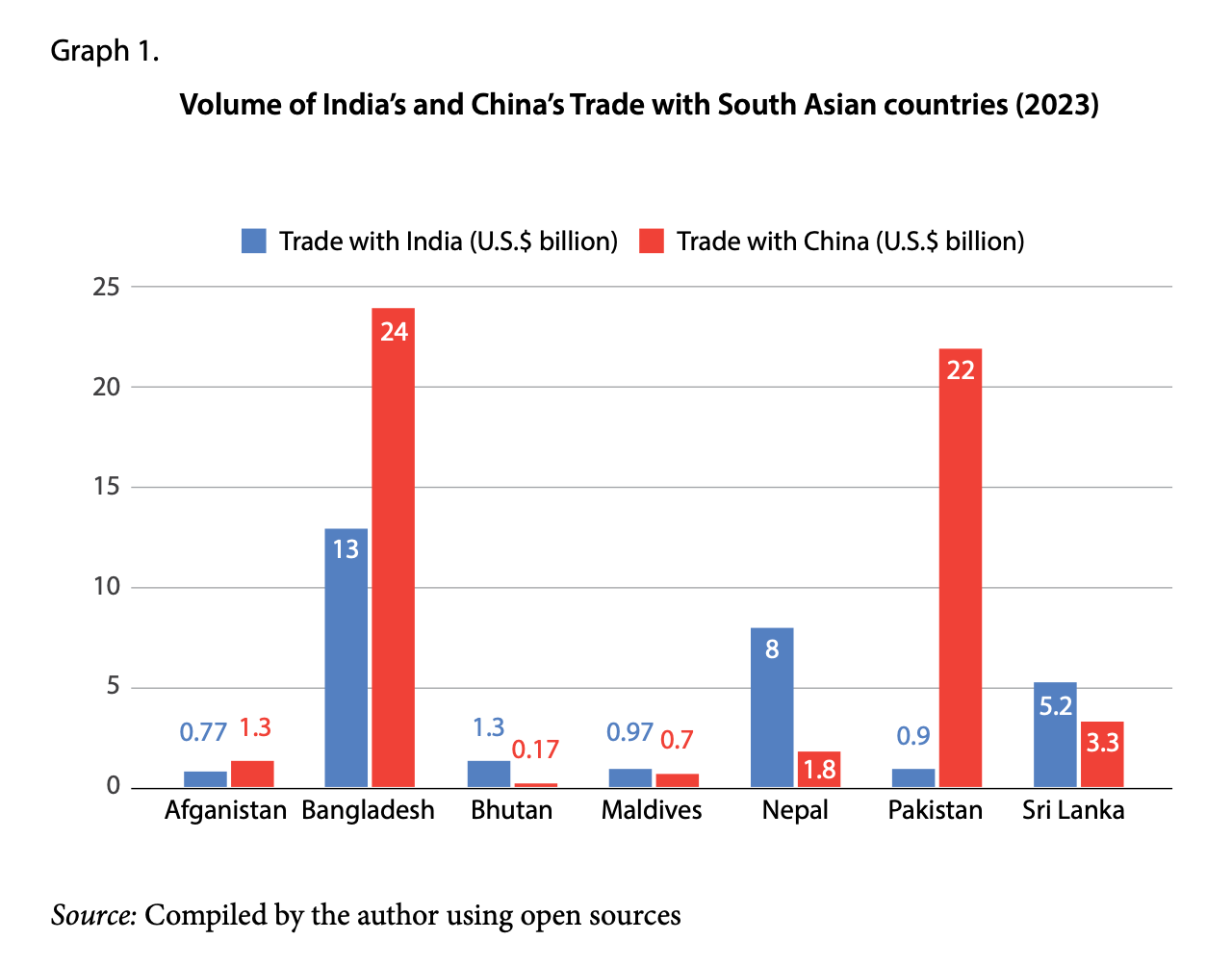

As China’s economy grew rapidly, it expanded its trade with countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh in South Asia (see Table 1). Its trade remains heavily concentrated on exports, with a steady increase seen since 2014 in the cases of Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. News reports indicate that China has become the largest overseas investor in Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka in recent years (Livemint, 2020). China also became the largest source of FDI in Bangladesh in 2022 (The Financial Express, 2022a), ahead of India (The Daily Star, 2022). New Delhi remains the leading investor in Nepal and Bhutan.

China has become a leading arms supplier to both Pakistan and Bangladesh. The expansion of Chinese naval capacities, and its rising influence with “key island states” like the Maldives and Sri Lanka raise Indian concerns (Tellis, 2009). The docking of a Chinese military surveillance ship in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port in 2022, and in the Maldives in 2024, has only underscored India’s concerns. The People’s Liberation Army has also been expanding its links with Nepal and Bangladesh, whereas earlier it was confined mostly to Pakistan and Myanmar (Baruah and Xavier, 2023). China has stepped up its infrastructure and connectivity projects in the subcontinent in recent years, especially since the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). All of India’s neighbors, except Bhutan, have joined the BRI. Within South Asia, Pakistan has received the largest share of BRI investment (Nouwens, 2023)—including for the India-opposed China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—followed by Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. The projects cover the areas of energy, transport, digital infrastructure, special economic zones, industrial parks, etc.

Some BRI projects have suffered from problems ranging from partner states’ financial situations (Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives) to delays in Nepal-China railway link and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). But India’s concerns regarding Chinese connectivity projects relate also to longer-term “geopolitical effects” (Minwang, 2020), including the “fears that China is using the BRI to encompass wider political, ideological, cultural, military, and social linkages” (Jacob, 2020) as well as to promote “Chinese-centric norms” in setting standards in “digital governance, security and development” (Nouwens, 2023). As China’s economic and infrastructure activities have expanded, so has its political influence in South Asia. It promotes links with political parties, offers scholarships to students and professionals, and expands media outreach to improve its image and build up its soft power (Jacob, 2020).

The scale of the BRI has added to preexisting Indian worries about the effect of Chinese inroads on the “choices of India’s neighbors” (Baruah and Xavier, 2023). China has increasingly supported parties in South Asia—Nepal, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Bhutan (Xavier, 2020a)—that have a more negative attitude towards India.

India and Other South Asian States

The changes in South Asia have been driven not just by the India-China equation, but also by the subcontinent’s smaller states’ balancing and bargaining with the two dominant powers, “play[ing] one…off against the other” (Xavier, 2017) to avoid overdependence and “check” the rising capabilities of both (Xavier, 2018).

The sheer geographic and economic size of India long prevented its neighbors from directly challenging its primacy, but the rise of China has given them leverage. China has helped South Asian states to diversify their trade. Countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal, and the Maldives were attracted to the BRI not only by the infrastructure on offer, but also by the prospect of escaping total dependence on New Delhi. The regional states use the India-China rivalry to “play one off against the other” to gain more benefits (Xavier, 2017), China is seen both as a “developmental partner” and a “balancing factor” with regard to India (Pal, 2021). The scale of its investments, staying power, and “less-conditional” offers of assistance are also viewed positively.

At the same time, most South Asian states tend to pursue a policy of engaging with multiple powers to avoid overdependence on any one major player and “check” the rising capabilities of both India and China (Xavier, 2018). Engagement or deals with one side are also sometimes used to signal displeasure or improve one’s bargaining position with the other (Pal, 2021). However, such policy shifts do not lead to a permanent breakdown of relations between the states.

For instance, the 2015 Indo-Nepalese supply crisis (which Nepal saw as a blockade by the Indian government) prompted Nepal to sign a Trade and Transit Agreement with China in 2016, acquiring access to seven Chinese ports that theoretically relieve it of dependence on India for trade (Giri, 2023). This, and the dispute over the Kalapani region (claimed by both India and Nepal but controlled by India) that flared up again in 2019, sparked Indian concerns that third parties might take advantage of the situation (Muni, 2020; The Wire, 2016). India made a “course correction,” building and improving cross-border rail, road, and waterway links and improving cargo movement of Nepali goods through Indian ports via an electronic system (Xavier, 2020b). Meanwhile, by 2023, the transit agreement with China had not led to any actual shipments. It was only in 2024 that Nepal sent its first batch of exports via Tianjin port in China (Xinhua, 2024).

The Maldives tilt towards India or China depending on their current government. The newly-elected Muizzu government is seen as close to China and campaigned on an ‘India Out’ platform, while the previous Solih government had a distinctly ‘India First’ approach (The Sunday Guardian, 2023).

India’s longer history in the region makes for more complicated relationships with its neighbors. Beijing has found it easier to present itself as a friendly actor while capitalizing on anti-Indian sentiment (Storey, 2023). However, it suffers from doubts about the long-term viability of some of its projects, from allegations of corruption, and from suspicions about its companies’ lack of transparency in their operations in smaller states. Lessons learnt from working with Chinese investors are shared across the region. Sri Lanka’s experience serves as a cautionary tale, while Bangladesh’s engagement with different partners appears as a good example to follow (Makarevich and Savishcheva, 2023).

While India is a leading trade partner for all of its neighbors except Pakistan, South Asia may constitute only 1.7%-3.8% of India’s total trade (Sinha and Sareen, 2020). Overall, South Asia remains one of the least integrated regions, with intra-regional trade at just 5% of the region’s trade with the outside world (Sinha and Sareen, 2020). The expansion of India’s ties in the subcontinent has not been smooth, plagued by project delays, insufficient infrastructure and investment, and accusations of “interference and bullying” (Xavier, 2020a).

The key for India is to respond to its neighbors’ needs, without repeating past mistakes, to avoid further loss of influence to China.

India has accordingly announced new programs such as ‘Neighborhood First’ and ‘Act East’ (2014), more investments, favorable deals etc. (Xavier, 2020a). However, India’s $650 million foreign aid budget (The Print, 2023)—of which about two-thirds is directed to South Asia (Lee, 2020)—remains small when compared to Chinese megaprojects like the BRI.

India’s Policy Shift

In response to these pressures, India has enacted a “striking change” in its policy (Bajpai, 2003), which previously sought to exclude external powers from South Asia. It now seeks the cooperation of states like the U.S., Japan, Australia, and France, which it perceives as sharing interests. This is both to bolster its own capacity to deliver in South Asia and also to capitalize on the concerns about China among other regional and global stakeholders to its benefit (Raja Mohan, 2023).

This has been visible in India’s engagement with several of its neighbors. In Sri Lanka, India has persuaded Japan to “re-engage” after the economic crisis that toppled the Rajapaksa presidency in 2022 (Baruah and Xavier, 2023), with plans to restart the East Container Terminal (ECT) project in Colombo. India, Japan, and France are jointly heading a committee to assist Colombo in its debt restructuring and economic recovery (Shivamurthy and Dutta, 2023). The U.S. has announced a loan for a terminal project on the port of Colombo where India’s Adani Group is the majority shareholder (Asia Financial, 2023). In Nepal, the U.S. has extended a $500 million grant for, among other things, enhancing Nepal-India electricity trade (U.S. Department of State, 2023). India is partnering with Japan in Bangladesh to develop infrastructure in the Bay of Bengal (Suzuki, 2024). Australia is investing $4.3 million to “support relationships across the LNG supply chain between Australia, India and Bangladesh” (Laskar, 2022). In 2021, India and the UK announced a Global Innovation Partnership program that will support the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals in South Asia (FCDO, 2022) through the transfer of Indian innovations.

India has also engaged with other multilateral initiatives like the Asian Development Bank, which has been implementing the South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) program that “brings together Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, and Sri Lanka in a project-based partnership” (ADB, 2023). It seeks to strengthen “multimodal cross-border transport networks” and infrastructure that boost trade and industrial growth (ADB, 2023). India has also announced its own multilateral initiatives like the International Solar Alliance and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure, with the participation of regional and some friendly extra-regional powers, but not of China (Xavier, 2023).

Policy Recommendations for Russia

Given this Indian approach, some policy recommendations can be offered for joint India-Russian cooperation in South Asia, which ought to be explored within a long-term framework.

- LNG provides an avenue for cooperation between India and Russia in Bangladesh. There, Novatek and H-Energy (India) have a memorandum of understanding regarding long-term LNG supply cooperation, regarding joint investment in future LNG terminals of H-Energy, and regarding the establishment of a joint venture to market LNG and natural gas not only to India, but also to Bangladesh and other markets. Natural gas (local production and imported LNG) meets about 59% of energy demand in Bangladesh (Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources, 2023). The country has been facing a gas crisis and its demand is expected to rise from 3,700 million standard cubic feet per day (mmscfd) in 2023 to 6,000 mmscfd within a decade (The Business Standard, 2024). Therefore, Dhaka is looking both to drill more gas wells and to increase its import of LNG through long-term contracts. At present, Bangladesh has four long-term deals for LNG with Qatar (2), Oman (1), and U.S.-based Excelerate Energy Inc (1). To deal with the current shortfall, the Bangladeshi government is now considering importing about 300mmcfd re-gasified liquefied natural gas (RLNG) from H-energy by 2025 (S&P Global Commodity Insights, 2023) via a cross-border pipeline from West Bengal to Bangladesh (Gas Outlook, 2023). It must be noted that there has been no update on the MoU with Novatek since it was signed in 2019.

- A 2014 India-Russia joint statement calls for examining “avenues for participation in petrochemical projects in each other’s country and in third countries. Such opportunities are available in Bangladesh, which has been interested in securing discounted oil from Russia. Due to the limitations of Bangladesh’s own refineries, this might best be done via India (The New Indian Express, 2022). At present, this arrangement faces challenges from the threat of sanctions and the absence of agreement on the details. Bangladesh’s crude oil imports could reach about 15 million tons by 2030 at current growth rates (Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources, 2023). The country also imports 4.3 million metric tons of refined petroleum products per annum, since diesel remains the dominant liquid fuel used in the country. Bangladesh has a long-term contract for the supply of high-speed diesel via the India-Bangladesh Friendship Pipeline, with a capacity of one million metric tons per annum (MMTPA), operating since 2023. The diesel will be transported from Numaligarh Refinery Limited (NRL) in West Bengal (India) to Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (Hindustan Times, 2023). NRL also plans to expand its exports to Nepal and would look at Myanmar once the internal situation stabilizes. NRL is working to expand its refinery capacity from 3 MMPTA to 9 MMTPA and will gradually start looking to import additional supplies of crude from abroad. While over 80% of NRL output is meant for the domestic markets, the rest is available for export. NRL has said that it would consider imports from Russia if they were economical (Mathur, 2024), which might become especially relevant given NRL’s construction of a crude oil import terminal at Paradip Port in Odisha on India’s eastern coast.

- India and Russia are already building the Rooppur nuclear power plant in Bangladesh, with Indian companies involved in “the construction, installation and supply of non-critical equipment” (Rosatom, 2018). A 2019 India-Russia joint statement reaffirmed the two sides’ readiness to expand such cooperation to other countries.

- India and Russia have also voiced readiness to continue cooperation in the defense sphere by transforming it from a buyer-seller relationship to joint production of military equipment, especially as India seeks to build an indigenous defense industry. The two sides also have ambitions to export their jointly manufactured products to third countries, as is evident from their agreement regarding the BrahMos supersonic cruise missile (TASS, 2016). They have also mentioned the possibility of “joint manufacturing in India of spare parts, components, aggregates and other products for maintenance of Russian-origin arms and defense equipment” for “export to mutually friendly third countries” (Embassy of India, 2021). This could offer less expensive arms to other South Asian states. At present, Indian servicing of Bangladesh’s Russian-origin equipment is a low-risk opportunity (Laskar and Singh, 2023).

- Russia can enhance its presence in the economically and strategically important Bay of Bengal through cooperation with India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. In November 2023, the Russian Navy conducted joint exercises with Myanmar and visited Bangladesh. India and Russia also have their own biennial naval exercises called Indra, but cooperation between their navies remains generally low. Russia’s naval presence in the Indian Ocean is also inherently limited (Brennan, 2023), and it must avoid upsetting either China or India. Its engagement with Beijing in the Indian Ocean has already caused some concern in New Delhi (Singh, 2019), which Moscow would do well to allay. Keeping these factors in mind, in the Bay of Bengal, the sides could look towards focusing on Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR), Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), maritime security, training, and provision of equipment. These areas build cooperation and goodwill while provoking little external concern and placing little strain on Russia’s limited naval capacities in the Indian Ocean.

- Russia and Sri Lanka have expressed intent to build a nuclear power plant in the latter. India could be invited as a partner following the Bangladesh example.

- India has a presence in the Sri Lankan renewable energy sector, where Russia could join. In 2024, an Indo-Russian joint venture won the contract to run for 30 years the Mattala international airport (located close to the Hambantota port), which was built by Chinese financing in 2013.

- Russia has indicated interest in providing technical assistance to Nepal’s hydropower (TASS, 2024b), which could become a site of trilateral cooperation with India, given the latter’s presence in Nepal’s energy sector.

- India has had to recalibrate its Afghanistan policy since the Taliban’s 2021 victory. Even though India does not subscribe to the idea that the Taliban are a source of regional stability, Russia is important to it as a conduit to the Taliban (Taneja, 2023). Indian and Russian interests converge in preventing the spread of terrorism and drug trafficking from Afghanistan, where engagement can be further strengthened.

- India and Russia could also collaborate to help the South Asian states achieve their Sustainable Development Goals, either trilaterally or through multilateral sector-specific initiatives like the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

* * *

The above discussion establishes the causes and extent of India’s policy shift towards external powers in South Asia. As it welcomes friendly extra-regional states, India seeks to maintain its own leading position by providing economic and infrastructural benefits to its neighbors. India and its smaller neighbors are looking to manage Chinese power in South Asia, but the smaller regional states also wish to pursue a balanced foreign policy and reap the benefits of multilateral economic engagement.

This has several implications for Russia.

First, Russia should start thinking about projects that it can propose in the region, to bolster its own presence and strengthen its partnership with India.

Second, joint projects with India would allow Russia to counter perceptions that its South Asia policy is “motivated by external reasons” (Topychkanov, 2017) and that the subcontinent is not its actual focus. A calibrated approach can help Russia to enhance its presence in a region where it is weak and competition is high.

Third, the Indian policy shift offers Russia an opportunity to reduce some of its overdependence on China in the East. While the intensification of competition in South Asia between India and China means that Russia will have to tread carefully to avoid antagonizing either of its partners, the pragmatism of South Asian states in welcoming extra-regional powers, including Russia, provides an opening.

Fourth, the rising presence and competition of great powers in South Asia means Russia will have difficulty establishing a foothold or being seen as a desirable partner, given that others have a lead in engaging with the subcontinent and Moscow has limited investment capacity. Hence, again, the need to cooperate with third parties, namely India.

Finally, the multiplicity of alignments between Western and Asian powers demonstrates how the latter are responding to the changing global balance of power. While the Global South does resist Western policies where necessary, it is also deeply pragmatic in pursuit of its interests, and Russia’s anti-Western message must be wielded carefully or not at all. Also, Russia would do well to understand various South Asian countries’ wariness towards China.

Russia’s efforts in the development-focused region will be complicated by its economic limitations, the absence of a comprehensive policy, and the demand for resources imposed by its confrontation with the West.

This article is an output of the research project “South Asia and the Challenges of Global Politics” within the Project Group Competition at HSE University’s Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs.

References

ADB, 2023. South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC). ADB. Available at: https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/topics/regional-cooperation/sasec [Accessed 12 March 2024].

Asia Financial, 2023. US Lends $553m to Adani Colombo Port JV amid China Rivalry. Asia Financial, 9 November. Available at: https://www.asiafinancial.com/us-lends-553m-to-adani-colombo-port-jv-amid-china-rivalry [Accessed 18 February 2024].

Bajpai, K., 2003. Crisis and Conflict in South Asia after September 11, 2001. South Asian Survey, 10(2), pp. 197-213.

Bajpai, K., 2021. South Asia’s Realist Future. In: C. Crocker et al. (eds). Diplomacy and the Future of World Order. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 156-178.

Bakshi, J., 1999. Russian Policy Towards South Asia. Strategic Analysis: A Monthly Journal of the IDSA, 23(8). Available at: https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/sa/sa_99baj04.html [Accessed 20 February 2024].

Baruah, D. and Xavier, C., 2023. How India and China Compete in Non-Aligned South Asia and the Indian Ocean. Brookings, 18 October. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-india-and-china-compete-in-non-aligned-south-asia-and-the-indian-ocean/ [Accessed 2 February 2024].

Bordachev, T., 2021. The Fall of Kabul and the Balance of Power in Greater Eurasia. RIAC, 2 September. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/comments/the-fall-of-kabul-and-the-balance-of-power-in-greater-eurasia/ [Accessed 14 August 2024].

Brennan, D., 2023. Russian Navy Wades into US-China-India Turf War. Newsweek, 14 November. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/russian-navy-wades-us-china-india-turf-war-indian-ocean-bangladesh-myanmar-1843571 [Accessed 21 January 2024].

Embassy of India, 2021. Joint Statement Following the XXI India-Russia Summit, “India-Russia: Partnership for Peace, Progress and Prosperity.” Embassy of India, 6 December. Available at: https://indianembassy-moscow.gov.in/press-releases-06-12-2021-2.php [Accessed 13 March 2024]

Energy Scenario of Bangladesh, 2024. Energy and Mineral Resources Division. Available at: https://hcu.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/hcu.portal.gov.bd/publications/ae775b7e_b63d_491d_81e4_b317ff8e11ca/2024-07-15-09-11-d13a3451b969fb9a3c5c74e9130c9f6c.pdf [Accessed 19 August 2024].

FCDO, 2022. UK-India Global Innovation Programme. Development Tracker, 10 November. Available at: https://devtracker.fcdo.gov.uk/projects/GB-GOV-1-300814/summary [Accessed 6 February 2024].

Forbes, 2024. The Maldives Has a Record Year of Tourism Thanks to Russia and China. Forbes, 8 February. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jimdobson/2024/02/08/the-maldives-has-record-year-of-tourism-thanks-to-russia-and-china/?sh=19b1850127bf [Accessed 10 February 2024].

Gas Outlook, 2023. Bangladesh Energy Crisis Spurs Pivot to Indian Gas. Gas Outlook, 1 November. Available at: https://gasoutlook.com/analysis/bangladesh-energy-crisis-spurs-pivot-to-indian-gas/ [Accessed 23 March 2024].

Giri, A., 2023. 7 Years Since Transit Deal with China, No Shipment Has Moved. The Kathmandu Post, 22 April. Available at: https://kathmandupost.com/national/2023/04/22/7-years-since-transit-deal-with-china-no-shipment-has-moved [Accessed 20 March 2024].

Gokhale, V., 2021. The Road from Galwan: The Future of India-China Relations. Carnegie India, 10 March. Available at: https://carnegieindia.org/2021/03/10/road-from-galwan-future-of-india-china-relations-pub-84019 [Accessed 18 February 2024].

Gubin, A., 2022. Russia-Sri Lanka Relations: The Eurasian Role of the “Emerald Island.” Valdai Discussion Club, 21 April. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/russia-sri-lanka-relations-the-eurasian-role/ [Accessed 11 January 2024].

Hindustan Times, 2023. Modi, Bangladesh’s Hasina Launch First Cross-Border Energy Pipeline. Hindustan Times, 18 March. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/pm-modi-bangladesh-s-hasina-launch-first-cross-border-energy-pipeline-101679139133933.html [Accessed 16 March 2024].

Ivashentsov, G., 2019. O politicheskikh protsessakh v Yuzhnoi Azii [On Political Processes in South Asia]. RIAC. Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/2019-southasia [Accessed 20 February 2024].

Izvestiya, 2023. Pochti dogovorilis: Rossiya i Pakistan obsuzhdayut dolgosrochny neftyanoi kontrakt [Almost Agreed: Russia and Pakistan Are Discussing a Long-Term Oil Contract]. Izvestiya, 22 November. Available at: https://iz.ru/1609468/sofia-smirnova/pochti-dogovorilis-rossiia-i-pakistan-obsuzhdaiut-dolgosrochnyi-neftianoi-kontrakt [Accessed 2 February 2024].

Jaishankar, S., 2022. Address by External Affairs Minister, Dr. S. Jaishankar at the Chulalongkorn University on “India’s Vision of the Indo-Pacific”. Ministry of External Affairs, 18 August. Available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/35641/ [Accessed 19 August 2024].

Jacob, J., 2020. China, India, and Asian Connectivity: India’s View. In: K. Bajpai et al. (eds). Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 315-332.

Joshi, Y. and Mukherjee, A., 2020. Offensive Defense: India’s Strategic Responses to the Rise of China. In: K. Bajpai et al. (eds). Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 227-239.

Kapoor, N., 2021. Russia’s Role in the New Afghanistan. ORF. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/SR-175_Afghanistan-and-the-New-Global-DisOrder_.pdf [Accessed 11 March 2024].

Korolev, A., 2023. “New Paradoxes” of Russian Policy in Asia. Valdai Discussion Club, 19 October. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/new-paradoxes-of-russian-policy-in-asia/ [Accessed 19 February 2024].

Laskar, R., 2021. India Again Kept Out of Extended Troika Meeting on Afghanistan Convened by Russia. Hindustan Times, 5 August. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-again-kept-out-of-extended-troika-meeting-on-afghanistan-convened-by-russia-101628105269003.html [Accessed 14 March 2024].

Laskar, R., 2022. India, Australia to Work Together on Trusted and Resilient Supply Chains: Jaishankar. Hindustan Times, 12 February. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-australia-to-work-together-on-trusted-and-resilient-supply-chains-jaishankar-101644674447224.html [Accessed 18 March 2024].

Laskar, R. and Singh, R., 2023. India Eyes Bangladesh as Market for Range of Military Hardware. Hindustan Times, 3 January. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-eyes-bangladesh-as-market-for-range-of-military-hardware-101672753197985.html [Accessed 3 March 2024].

Lee, S., 2020. Unequal Rivals: China, India, and the Struggle for Influence in Southeast Asia. In: K. Bajpai et al. (eds). Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 434-448.

Livemint, 2020. Mapped: How China Has Raised Its Clout in India’s Neighbourhood. Livemint, 30 June. Available at: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/mapped-how-china-has-raised-its-clout-in-india-s-neighbourhood-11593498026189.html [Accessed 5 February 2024].

Makarevich, G. and Savishcheva, M., 2023. Yuzhnaya Aziya i initsiativa “Poyas i Put”: ot konfrontatsii k kooperatsii i obratno [South Asia and the Belt and Road Initiative: From Confrontation to Cooperation and Back). In: V. Mikheev (ed). Novaya realnost Indo-Tikhookeansogo prostranstva [A New Reality in Indo-Pacific Space]. Moscow: IMEMO RAS, pp. 108-115.

Mathur, S., 2024. NRL Expects Commissioning of Expanded Refinery by Dec 2025, Says MD. Moneycontrol, 24 February. Available at: https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/mc-interview-nrl-expects-commissioning-of-expanded-refinery-by-dec-md-12314841.html [Accessed 20 February 2024].

MID, 2022. Russian–Sri Lankan Relations. MID, 7 July. Available at: https://sri-lanka.mid.ru/en/countries/rossiysko_lankiyskie_otnosheniya/ [Accessed 17 March 2024].

MID, 2024. Press Release on Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s Meeting with Foreign Minister of Sri Lanka Ali Sabry. MID, 10 June. Available at: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1955695/ [Accessed 19 august 2024]

Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources, 2023. Energy Scenario of Bangladesh 2021–2022. Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources [online]. Available at: http://www.hcu.org.bd/sites/default/files/files/hcu.portal.gov.bd/publications/da1f3395_2c8f_4608_a48c_d184d5925d45/2023-03-14-07-47-0d3be29ec0b5cfc0dc6055e8eec23e37.pdf [Accessed 1 March 2024].

Minwang, L., 2020. China, India, and Asian Connectivity: China’s View. In: Bajpai, K. et al. (eds). Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 303–314.

Muni, S.D., 2020. Lipu Lekh: The Past, Present and Future of the Nepal-India Stand-Off. Hindustan Times, 22 May. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/lipu-lekh-the-past-present-and-future-of-the-nepal-india-stand-off-analysis/story-wy3OvSD0G0nkxtGQTOIp2I.html [Accessed 8 February 2024].

Nouwens, M., 2023. China’s Belt and Road Initiative a Decade On. IISS. Available at: https://www.iiss.org/globalassets/media-library—content—migration/files/publications—free-files/aprsa-2023/aprsa-2023.pdf [Accessed 1 March 2024].

Pal, D., 2021. China’s Influence in South Asia: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 13 October [online]. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/13/china-s-influence-in-south-asia-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries-pub-85552 [Accessed 5 February 2024].

Raja Mohan, C., 2023. India, Japan and South Asia Geoeconomics. ISAS, 19 April. Available at: https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/india-japan-and-south-asia-geoeconomics/ [Accessed 8 February 2024].

RIA Novosti, 2023. Pakistan izuchit vozmozhnosti uvelicheniya postavok nefti iz Rossii [Pakistan Explores Opportunities to Increase Oil Supplies from Russia]. RIA Novosti, 8 December. Available at: https://ria.ru/20231208/neft-1914726675.html [Accessed 5 February 2024].

Rosatom, 2018. Indian Industry Participates in Construction of Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant. Rosatom, 7 December. Available at: https://www.rosatom-southasia.com/press-centre/rosatom-in-media/indian-industry-participates-in-construction-of-rooppur-nuclear-power-plant/ [Accessed 8 March 2024].

Sareen, S., 2022. India’s Outreach to the Taliban: Engage, Don’t Endorse. ORF, 8 June. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-outreach-to-the-taliban [Accessed 12 February 2024].

Shivamurthy, G.S. and Dutta, A., 2023. Harbouring France in the Indo-Pacific: Assessing Macron’s Visit to Sri Lanka. ORF, 10 August. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/harbouring-france-in-the-indo-pacific [Accessed 29 January 2024].

Singh, A., 2019. Russia’s Engagement in the Indian Ocean: A View from New Delhi. Valdai Discussion Club, 16 December. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/russia-s-engagement-in-the-indian-ocean-a-view-fro/ [Accessed 13 March 2024].

Sinha, R. and Sareen, N., 2020. India’s Limited Trade Connectivity with South Asia. Brookings, 26 May. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/indias-limited-trade-connectivity-with-south-asia/ [Accessed 5 February 2024].

SIPRI, 2022. Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2021. SIPRI. Available at: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/fs_2203_at_2021.pdf [Accessed 13 March 2024].

Smith, J., 2020. The China–India–US Triangle: A View from Washington. In: Bajpai, K. et al. (eds). Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 365–379.

S&P Global Commodity Insights, 2023. Bangladesh Plans to Clear LNG Debt, Boost Imports, Gas Production. S&P Global Commodity Insights, 28 September. Available at: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/lng/092823-interview-bangladesh-plans-to-clear-lng-debt-boost-imports-gas-production [Accessed 23 March 2024].

Sputnik India, 2024. Russia-Bangladesh Trade Turnover Sees 16.5% Surge, Hitting $2.7 Bln Mark. Sputnik India, 30 May. Available at: https://sputniknews.in/20240530/russia-bangladesh-trade-turnover-sees-165-percent-surge-hitting-27bln-mark-7488876.html#:~:text=generation%20and%20shipbuilding.-,Trade%20volumes%20between%20Bangladesh%20and%20Russia%20saw%20a%20jump%20of,increase%20in%20bilateral%20trade%20flows. [Accessed 12 August 2024].

Stepanova, E., 2018. Russia’s Afghan Policy in the Regional and Russia-West Contexts. IRFI, 15 May. Available at: https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/rnr_23_stepanova_russia_afpak_2018.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2024].

Storey, H., 2023. India Doubles Down on Regional Connectivity to Counter China. Lowy Institute, 21 August. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/india-doubles-down-regional-connectivity-counter-china [Accessed 8 February 2024].

Suzuki, H., 2024. Keynote Address by H.E. Hiroshi Suzuki, Ambassador of Japan to India, at the 4th India-Japan Intellectual Conclave. 12 February [online]. Available at: https://www.in.emb-japan.go.jp/files/100622214.pdf [Accessed 19 August 2024].

Tanjea, K., 2023. India Still Needs to Work with Russia on Afghanistan. Lowy Institute, 21 August. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/india-still-needs-work-russia-afghanistan [Accessed 23 March 2024].

TASS, 2016. India, Russia Agree to Export BrahMos Missiles to Third Countries – Spokesman. TASS, 27 May. Available at: https://tass.com/defense/878650 [Accessed 15 January 2024].

TASS, 2023. Pakistani Company Clinches Long-Term Oil Supplies Contract with Russia – Express Tribune. TASS, 19 October. Available at: https://tass.com/economy/1693493 [Accessed 19 January 2024].

TASS, 2024a. Russia’s Wheat Exports Rise by 11% to 40.85 mln tons — Experts. TASS, 8 April. Available at: https://tass.com/economy/1772083 [Accessed 14 August 2024].

TASS, 2024b. Nepal Suggests Russia Invest in Country’s Hydropower Industry, Production of Fertilizers. TASS, 21 March. Available at: https://tass.com/economy/1763295 [Accessed 4 February 2024].

Tellis, A., 2009. US and Indian Interests in India’s Extended Neighbourhood. In: Ayers, A. and Raja Mohan, C. (eds). Power Realignments in Asia: China, India and the United States. New Delhi: Sage Publications India Private Ltd, pp. 221–248.

The Business Standard, 2024. As Local Gas Runs Out, $1.4b Pipeline Planned to Boost Imported LNG Supply. The Business Standard, 21 January. Available at: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/energy/local-gas-runs-out-14b-pipeline-planned-boost-imported-lng-supply-778458 [Accessed 16 March 2024].

The Daily Star, 2022. PM Urges Indian Firms to Invest in Bangladesh. The Daily Star, 8 September [online]. Available at: https://www.thedailystar.net/business/economy/news/pm-urges-indian-firms-invest-bangladesh-3113961 [Accessed 25 December 2023].

The Financial Express, 2022a. China Now Largest FDI Source of BD. The Financial Express, 18 December. Available at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/economy/bangladesh/china-now-largest-fdi-source-of-bd-1671331967 [Accessed 25 December 2023].

The Financial Express, 2022b. Gazprom Rallying Rigs to Drill Three Onshore Wells. The Financial Express, 16 January. Available at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/national/gazprom-rallying-rigs-to-drill-three-onshore-wells-1642302533 [Accessed 25 December 2023].

The Financial Express, 2023. Sanctions against Russia: EEC Skips BD Visit Ahead of JWG Meeting. The Financial Express, 26 March. Available at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade/sanctions-against-russia-eec-skips-bd-visit-ahead-of-jwg-meeting [Accessed 16 March 2024].

The New Indian Express, 2022. Bangladesh Looking For Russian Oil at Discounted Rates via India, in Talks with Rosneft. The New Indian Express, 7 September. Available at: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2022/Sep/06/bangladesh-looking-for-russian-oil-at-discounted-rates-via-indiain-talks-with-rosneft-2495581.html [Accessed 16 March 2024].

The Print, 2023. India’s Aid to Bhutan Rises from Rs 2,266 Crore to Rs 2,400 Crore, Reflects Its Neighbourhood First Policy. The Print, 27 February. Available at: https://theprint.in/world/indias-aid-to-bhutan-rises-from-rs-2266-crore-to-rs-2400-crore-reflects-its-neighbourhood-first-policy/1405081/ [Accessed 13 March 2024].

The Sunday Guardian, 2023. Alarm Bells as Maldives Goes from ‘India First’ to ‘India Out.’ The Sunday Guardian, 8 October. Available at: https://sundayguardianlive.com/top-five/alarm-bells-as-maldives-goes-from-india-first-to-india-out [Accessed 13 August 2024].

The Wire, 2016. India’s “Blockade” Has Opened the Door for China in Nepal. The Wire, 2 March. Available at: https://thewire.in/diplomacy/indias-blockade-has-opened-the-door-for-china-in-nepal [Accessed 2 March 2024].

Topychkanov, P., 2017. Where Does Pakistan Fit in Russia’s South Asia Strategy? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 16 January. Available at: https://carnegiemoscow.org/2017/01/16/where-does-pakistan-fit-in-russia-s-south-asia-strategy-pub-67696 [Accessed 25 December 2023].

US Department of State, 2023. Clean EDGE Asia: Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Nepal Compact Entered into Force. US Department of State, 31 August. Available at: https://www.state.gov/clean-edge-asia-millennium-challenge-corporation-mcc-nepal-compact-entered-into-force/ [Accessed 12 January 2024].

US Department of Treasury, 2023. Treasury Imposes Sanctions on More Than 150 Individuals and Entities Supplying Russia’s Military-Industrial Base. US Department of Treasury, 12 December. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1978 [Accessed 26 January 2024].

Valdai Discussion Club, 2023. Russia and Asia: The Paradoxes of a New Reality. Valdai Discussion Club. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/files/42159/ [Accessed 12 January 2024].

Xavier, C., 2017. India’s “Like-Minded” Partnerships to Counter China in South Asia. Centre for the Advanced Study of India, 11 September. Available at: https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/iit/constantinoxavier [Accessed 23 February 2024].

Xavier, C., 2018. Bridging the Bay of Bengal: Toward a Stronger BIMSTEC. Carnegie India, 22 February. Available at: https://carnegieindia.org/2018/02/22/bridging-bay-of-bengal-toward-stronger-bimstec-pub-75610 [Accessed 12 January 2024].

Xavier, C., 2020a. Across the Himalayas: China in India’s Neighbourhood. In: Bajpai, K. et al. (eds). Routledge Handbook of China–India Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 420-433.

Xavier, C., 2020b. Interpreting the India-Nepal Border Dispute. Brookings, 11 June. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/interpreting-the-india-nepal-border-dispute/ [Accessed 12 January 2024].

Xavier, C., 2023. India’s Optimism for a New Regional Order. RSIS, 31 January. Available at: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/indias-optimism-for-a-new-regional-order/ [Accessed 26 January 2024].

Xinhua, 2024. Nepal Ships 1st Batch of Exports under Transit Deals with China. Xinhua, 25 January. Available at: https://english.news.cn/20240125/c85262674bcf4fbc8051b2d5d9a0c074/c.html [Accessed 26 March 2024].

Zakharov, A., 2024a. Russia Is Re-Emerging in South Asia. ORF, 23 February. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/russia-is-re-emerging-in-south-asia [Accessed 14 March 2024].

Zakharov, A., 2024b. From Neglect to Revival: Making Sense of Russia’s Outreach to Bangladesh. ORF, Issue Brief No. 689, pp. 1-23.

By Russia in Global Affairs | Created at 2024-10-01 09:00:51 | Updated at 2024-10-01 19:28:42

13 hours ago

By Russia in Global Affairs | Created at 2024-10-01 09:00:51 | Updated at 2024-10-01 19:28:42

13 hours ago