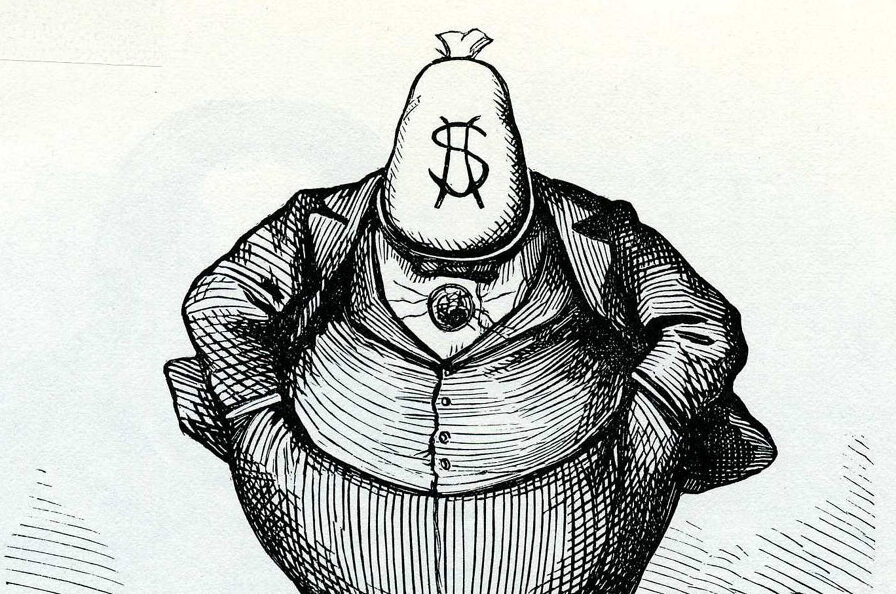

Book titles that begin “The Treasury of …” suggest a box that you open to find jewels inside. The Treasury of Folklore: Waterlands, wooded worlds and starry skies looks and feels like a heavy box, its thick card-like pages bound inside black and gold boards. It’s lavishly illustrated with woodcuts by Joe McLaren (though I had to search to find his name) and the introduction invites the reader to “dive deep” for the marvels that lie within.

Dipping is probably better than diving. This compilation mixes stories, beliefs and traditions in an explanatory frame designed to illuminate our “shared humanity”. Folklore is “timeless”, reflecting “primal fears and dreams” because “we are all inherently the same”. In this book “the wisdom of communities across the world” that has been passed down through the generations is gathered and made available to help “build bridges between people from all places”.

There is a problem with this laudable ambition of which the compilers are aware. They have assembled a selection of materials originally published in three separate volumes (Maypoles, Mandrakes and Mistletoe, 2018, Woodlands and Forests and Seas and Rivers, both 2021) for an English-language readership. The stories “unearthed” from India, Japan, Africa, Finland, Turkey, Guatemala and so on sometimes reveal startling similarities: multiple famous floods, for example, while Noah appears in the Christian Bible, the Jewish Torah and the Islamic Quran. There are sea monsters, mysterious islands and water deities a-plenty, along with sacred rivers and lost cities; there are ghost ships, mermaids, skeleton crews. But there are also differences that can’t be subsumed under the bromides of “magical” and “enchanted”. Lip service is paid to the undesirability of acts of cultural appropriation, but the assumed addressee is someone who might find some of the language used “unfamiliar” because they don’t “share its heritage”; or who, like the wearer of a popular tattoo, the China koi fish, knows nothing of its ancient story and is gently reproved. The symbolic meaning of the fish – courage and determination – has travelled without its accompanying tale, “another example of how traditions can be appropriated by others across the world”.

The didactic tone can be wearing. The content, lightly researched and not referenced, is delivered in prose that is uniformly utilitarian, deferential, decent and lacking variety. The four paragraphs of the chapter “The Hare”, illustrating the common idea that a rabbit or hare lives on the moon, begin as follows: “In a story in the Buddhist Sasa-jātaka …”, “In a tale from Sri Lanka …”, “In a different vein, according to a tale from South Africa …”, “According to Aztec tradition …”. There is relief in moving from brief summaries to fully told tales such as “The Morning Star and the Evening Star” from Romania (featuring, inter alia, an empress, a child, a witch, a prince, hair and a fish bone). But then we’re back again with short sections beginning, “According to Latvian and Lithuanian tradition …”, “According to Greek Mythology …”.

It’s tricky finding timeless meanings in time-bound human history. Sacred rivers like the Ganges are foully polluted. How did that happen? What to do about it? The fact is mentioned and we pass on. More space is given to a critique of the Russian tale “Vasilisa the Beautiful” featuring Baba Yaga, a witch whose stories “are not for the faint-hearted”. (She eats children.) Is she nefarious or does she teach the value of older women? Do older women have value? The section “Forest Hags from Around the World” suggests they have traditionally been thought of as evil crones: Yama-uba in Japan, Batibat in the Philippines, Likho in Russia and Muma Pădurii in Romania all share Baba Yaga’s cannibalistic tendencies. As such, we are told, they reflect an “outdated idea” now that “women are reclaiming their power”. Are they? Can we be sure? And does that mean everywhere? For ever? It would be nice to think so but recent changes to abortion law in America, for example, suggest otherwise.

Folklore preserves mixed messages. The banyan tree, one of 750 types of fig, is revered in India. They can grow to a huge size, in width rather than in height: around 20,000 people are said to be able to shelter beneath the 500-year-old Thimmamma Marrimanu tree in Anantapur, near Andhra Pradesh. The tree offers protection, but like the yew the banyan is linked with death: in Hindu belief, Shiva, the god of destruction, is shown sitting on a banyan leaf. In the nineteenth century British troops in India found the banyan convenient for executions: a hundred men at a time (“rebels”) could be hung from one tree, and they were.

Norma Clarke is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at Kingston University. Her most recent book is a family memoir, Not Speaking, 2019

The post Magical thinking appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:33:58

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:33:58

1 week ago