On March 31, the Paris criminal court found Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Rally (RN) parliamentary group in the National Assembly, guilty of embezzling public funds and sentenced her to five years of electoral ineligibility, four years in prison (two suspended and two of home arrest with electronic monitoring), and a €100,000 fine.

The crime? Using European Union funds from 2004 through 2016 to pay staff who, instead of working for the EU in Brussels, worked mainly for the RN in France. This probably knocks her out of the running for the 2027 presidential election, even though she is currently the leading candidate.

It has been common to use Euro-parliament funds for domestic politics, but the court picked a side, and it wasn’t Miss Le Pen’s. The hard-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon, and his North African PR woman, Sophia Chikirou (with whom he appears to have more than a professional relationship), for example, have been accused of similar misconduct but are probably not in much danger.

Nine other RN members who had served as Euro-deputies also received fines and prison sentences, including the former number-two in the party, Bruno Gollnisch, who spoke at American Renaissance conferences in 2000 and 2008. Also found were guilty were Miss Le Pen’s sister, Yann Le Pen, and the Le Pen family’s faithful bodyguard, Thierry Légier. The current mayor of Perpignan, Louis Ailot, was fined €20,000 and received a two-year ban from public office, but the ban was subject to appeal — unlike Miss Le Pen’s ban — and he remains in office.

The RN’s defense strategy was a disaster. Although Miss Le Pen practiced law from 1992 to 1998, she conducted a poor defense, claiming total innocence in what she called a purely political trial. This was implausible in light of evidence that included testimony by people who were supposed to be Euro-Parliament assistants but who had never even seen their MEPs in Brussels.

Clearly, the judges’ politics played a role, often leaning toward the left or even the far left, but this was all the more reason to have a rock-solid defense rather than naively asserting innocence. Claiming it was a witch hunt might rally public sympathy, but it did not work in the courtroom. Like many in France, Miss Le Pen believed that even if she were barred from future elections, her ineligibility would be subject to appeal and would not take effect until all appeals were exhausted. Stunned by the verdict and by the immediate effect of her five-year ban, Miss Le Pen stormed out of the courtroom before the entire judgment was even read.

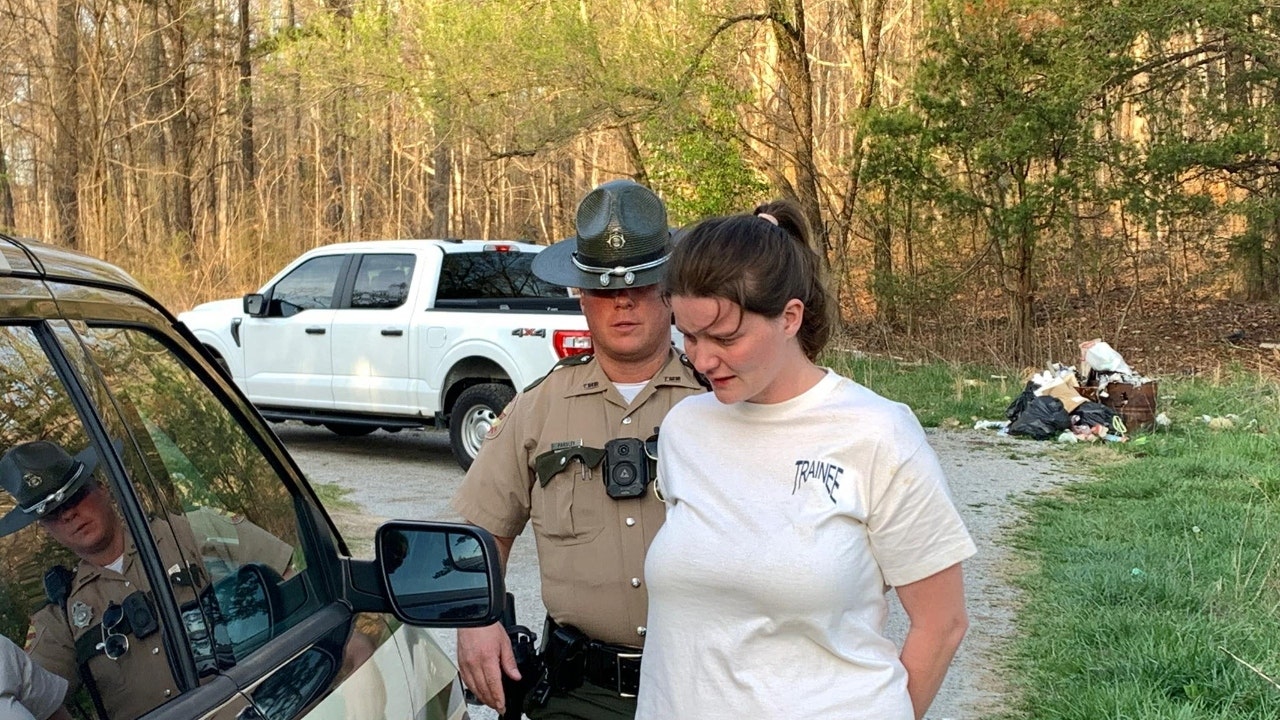

Marine Le Pen leaves the court after her trial. (Credit Image: © Maxppp via ZUMA Press)

Bénédicte de Perthuis, the 63-year-old presiding magistrate, has had much experience in high-profile cases. She justified her harsh sentence as a necessary step to ensure that politicians get no special treatment. She also unwittingly reminded the French public that the legal system can be strangely tough when dealing with politicians it dislikes — in contrast to its treatment of criminals, illegal immigrants, and Muslim radicals.

Miss Le Pen probably has little chance of competing in the 2027 presidential election. She filed an immediate appeal, which will reportedly be heard on an expedited basis. The French appeals process is usually slow, but the court promises a decision by the summer of 2026. Even if her ban were lifted on appeal, the decision might not come in time for her to be a candidate. Miss Le Pen is now nothing more than the RN’s parliamentary group leader, without even a seat in the Euro-parliament. Her only remaining influence for 2027 lies in her moral and intellectual hold over the current president of the RN, Jordan Bardella.

Europe remains a minefield for populists. In Romania, the traditionalist, populist, anti-globalist Călin Georgescu, who seemed poised to win the presidential election in 2024, was disqualified by the courts. In Germany, the nationalist Alternative for Germany is locked out of power, despite being the second-most popular party. In France, Miss Le Pen’s conviction reinforces longstanding skepticism of a judiciary often seen as a tool of the elite. That sentiment is amplified by the fate of Nicolas Sarkozy, a conservative former president of France, who has been interminably entangled in criminal cases and is even now under house arrest with electronic monitoring.

With Miss Le Pen probably out of the running, the RN must now rely on Jordan Bardella for 2027. At 29, he is the party’s rising star, a formidable debater who effortlessly humiliates his opponents — a skill Miss Le Pen can no longer muster.

However, Mr. Bardella does not have unanimous support within the party. He faces the same factional infighting that has plagued the French Right since the days of Vercingetorix. Senior RN figures resent his naked ambition, his perceived disloyalty to the Le Pen legacy, his “TikTok culture,” his Parisian leadership style disconnected from the party’s more blue-collar grassroots, and his record of sidelining veteran regional leaders. He is modern, he has looks, style, and physical presence (he is 6’3″), and is very popular with young women and girls. He already knows how powerful his charm is, but he is still far from a unifying force.

Jordan Bardella (Credit Image: © Imago via ZUMA Press)

Mr. Bardella’s past has drawn scrutiny from the Left. In January 2024, France 2 television reported that between 2015 and 2017, he allegedly posted “racist” comments under the pseudonym “RepNat du Gaito” on Twitter. For example, he was said to have posted a doctored image of Jean-Marie Le Pen in a boxing ring with a black boxer, along with the text: “You dare defy me? I’ll knock your pants off.”

He also posted an image of two white men in a swimming pool surrounded by non-whites who are saying: “LMAO at the Créteil swimming pool. Those two are wondering ‘how did I end up here?’ ”

He posted the same image with the caption “The Black Sea.”

Three former associates, seeking their moment of fame, confirmed that Mr. Bardella was behind the account, but he denies it outright. If these tweets are authentic, they suggest a more radical outlook than Mr. Bardella’s current public persona, perhaps an inclination toward policies such as “remigration” — a term he never uses. They may reflect a young unpolished activist, enjoying the humor of the far-right’s harder edge before adopting Miss Le Pen’s softening strategy of “detoxification.”

Meanwhile, Miss Le Pen’s own decisions have alienated her identity-driven voter base. In 2024, she pressured Germany’s AfD to drop the term “remigration” as too explosive, even though many see it as the only way to restore Europe’s identity. This frustrated her party’s hardline faction and gave Mr. Bardella room to position himself to her right. He has also never spoken about Islam as acceptingly as Miss Le Pen has.

In 2018, she told the magazine Valeurs Actuelles, “Islam can be integrated into the [French] Republic if its representatives accept that the laws of the Republic take priority over religious law.” When asked on the French television station TF1 if Islam is “compatible” with the Republic, she said, “Yes, I think so. An Islam of the kind we have known, secularized by the Enlightenment like other religions.”

This has infuriated the RN’s nationalist wing, which is fed up with compromises. For them, she is no longer seen as a rallying figure but as a leftist. Mr. Bardella has avoided this mistake. Miss Le Pen’s attempts to straddle both worlds — placating identity-conscious voters while dreaming of a patriotic Muslim electorate — have satisfied neither non-white voters nor the rural whites who revere her almost as a saint-like figure.

Therefore, the judiciary’s decision to sideline Miss Le Pen may have unleashed a more formidable opponent to the system in the form of Jordan Bardella. He is not always easy to pin down, but his political skill is undeniable. In 2027, he could dominate his rivals in debates, whereas Miss Le Pen faltered in the face of the slippery Emmanuel Macron. The judges in this case may not have anticipated the political force they are potentially unleashing.

Mr. Bardella, unlike Miss Le Pen, does not seem to have a visceral aversion to identitarianism. His strategic silences — and perhaps those old tweets — resonate with those seeking a more decisive voice, whereas Miss Le Pen’s caution held her back. Mr. Bardella may temper his rhetoric for now, but he may be quietly holding firm positions on immigration. Still, he will have to win over the RN’s soul.

Without the “Saint Marine” adored by rural whites, can he unify the party? At least for now, RN voters are angry: “They’re stopping me from voting for my candidate.” That frustration could fuel a sense of electoral revenge, a force Mr. Bardella will need to harness.

Some voices, such as former Sarkozy advisor Henri Guaino, have called for pardoning Miss Le Pen, arguing that judicial campaigns should not dictate the course of democracy. Internationally, former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro decries “left-wing judicial activism,” Hungarian President Viktor Orbán declares, “I am Marine!” and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who had recently warmed to Miss Le Pen, has called the court’s ruling an attack on democratic principles. Even Miss Le Pen’s bitter opponent, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, welcomed the guilty verdict but not the candidacy ban, noting that “the decision to remove a politician from office should be decided by the people.” Others on the far left fear a massive sympathy vote in favor of the RN.

The party’s future, and that of a large segment of the French Right, hinges on Mr. Bardella’s ability to navigate these turbulent waters. While Miss Le Pen may have exited the main stage, her shadow will linger. Inheriting this charged landscape, Mr. Bardella has a unique opportunity: to redefine his party and establish himself as a leading figure for 2027. Yet his success will depend not only on his debating prowess but also on his ability to mend internal divisions and channel public discontent — a precarious but critical balancing act.

By American Renaissance | Created at 2025-04-02 22:58:47 | Updated at 2025-04-04 01:48:20

1 day ago

By American Renaissance | Created at 2025-04-02 22:58:47 | Updated at 2025-04-04 01:48:20

1 day ago