For citation, please use:

Silaev, N.Yu., 2024. Middle Powers Revisited: “Good Citizens” of the World Majority. Russia in Global Affairs, 22(4), pp. 118–135. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2024-22-4-118-135

The concept of the World Majority, proposed by Sergei Karaganov,[1] has quickly entered Russia’s foreign policy vocabulary and pro-Russian foreign policy discourse. A Google search query for “World Majority” (“мировое большинство”) on the Russian Foreign Ministry’s website returned 946 documents as of 10 September 2024, even though the concept appeared only in the fall of 2022. For comparison, a similar search for “traditional values” returned 693 results, although this concept has for many years been central to Russian foreign and domestic policy.

Although the term ‘World Majority’ still lacks a generally accepted and academically precise definition, its popularity in Russia is understandable: it satisfies several needs created by the Special Military Operation (SMO). First, it permits the identification of countries that have not joined the West’s anti-Russian coalition. These make up the majority of the world’s countries and, thanks to China and India, represent the majority of the world’s population and more than half of the global economy.

Russia’s references to the World Majority thus repudiate Western efforts to isolate it and suggest that many states of the Majority share Russia’s positions on important issues.

And second, by joining Russia with the Global South, the ‘World Majority’ concept places Russia’s conflict with the West within the context of the world’s liberation from the “golden billion” (Karaganov et al., 2023, pp. 10, 15-19).

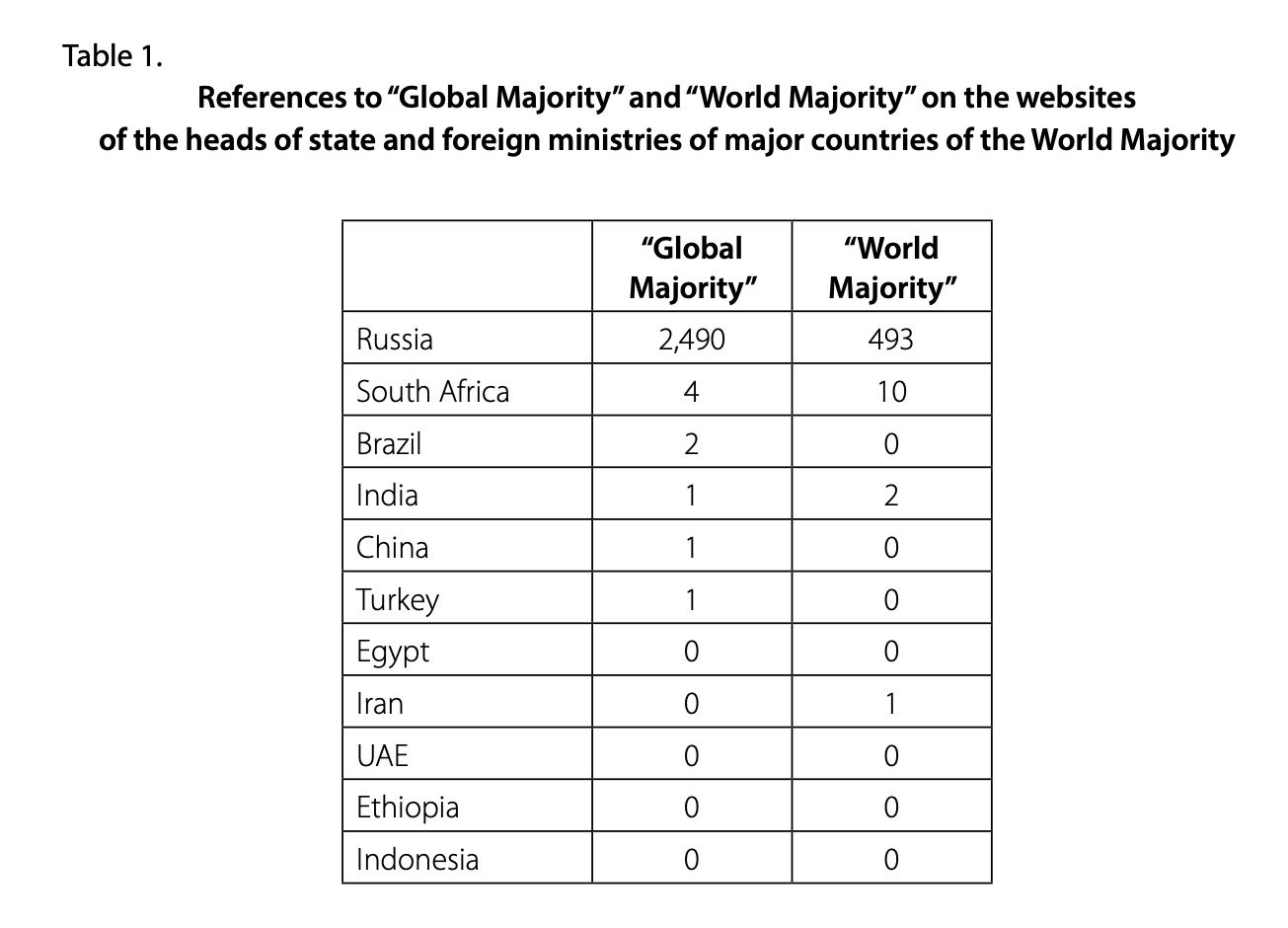

However, the term ‘World Majority’ has not (yet?) become popular among those to whom it refers. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s website does not mention the “Global Majority” at all, and “World Majority”[2] appeared just once in a speech on climate change in November 2015.[3] The Russian-language version of the Chinese MFA’s website does not use the term, either.[4] Table 1 shows the uses of “Global Majority” and “World Majority” on the websites of the heads of state and foreign ministries of the members of BRICS, Turkey, and Indonesia.

The concept’s ambiguousness and vagueness are not a problem, though. Like any political concept, its function is less analytical than it is performative and constitutive, and it “may contribute to producing what it appropriately describes or designates” (Boudieu, 1991, p. 220). However, outside of Russia, representatives of the World Majority themselves do not use the term. This contradiction can be interpreted in two ways. The first approach—more consistent with Russia’s area-studies-focused approach to international relations—is to analyze the political rhetoric of each country in order to find out why it accepts or does not accept a certain concept. The second approach would proceed through the system of international relations, which seems warranted, given that the World Majority exists within such a systemic context, and given that such a system cannot be reduced merely to the sum of its participants (Tsygankov, 2013).

In my opinion, the World Majority should be considered with reference to the new middle powers—those whose military and economic capabilities do not enable them to seek great power status, but who highly value their sovereignty and seek a non-hegemonic international order with institutions free of Western dominance.

Defining them as new middle powers reflects both continuity and a break with the concept of a ‘middle power,’ which has been used in IR studies for several decades. However, ‘middle power’ is a controversial and difficult notion. Some have long suggested abandoning it completely (more on this below). Realism defines it as a state that is materially weaker than the great powers, but stronger than the rest: e.g., the Ottoman Empire and Italy during World War I. But there is also the liberal tradition of studying middle powers as states that play a special role in creating and maintaining the international order and its institutions. This tradition produced the ‘behavioral’ definition of middle powers as states seeking international influence through multilateral diplomacy and compliance with international norms (i.e., those of the liberal order). While the realist definition applies well to maneuverings within the balance of power (e.g., middle powers’ alignment with military blocs), it says little about the international order. The liberal approach, conversely, can explain behavior within the context of the liberal international order, but not once that order collapses.

The new middle powers are not regional powers in the sense of having regionally bounded influence and interests, as the very nature of the modern international system is not conducive to regional isolation. They make up a large fraction of the countries in the world.

As “good citizens” of the World Majority, they have more influence than small states do, and play a decisive role in forming new international institutions with a special role in the emerging (no longer liberal) international order.

Elusive Middle Power

Carsten Holbraad, the author of a detailed and highly cited study on middle powers (Holbraad, 1984), refers to the notes of renowned British IR scholar Martin Wight (a founder of the English School of IR) and traces middle power theory back to Giovanni Botero, a 16th-century Savoyard philosopher, diplomat, and priest. Other researchers have located the concept in China as early as the 6th century BC (Abbondanza, 2018). As for the concept’s political problematization, Holbraad traces it to the Congress of Vienna, when the post-Napoleonic Concert of Europe raised the question of states’ hierarchy. This involved the realist version of the concept: those weaker than the strongest, but stronger than the weakest.

The liberal version of the concept emerged out of discussions in 1944-1945 about the UN’s structure, when states like Canada, Australia, and Brazil sought special rights for those with significant economic capabilities, with leading positions in their regions, or otherwise able to make significant contributions to international security. Importantly, they specifically sought the distinction, within the international hierarchy, of states that are not great powers but still have significant capabilities. Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King warned that the world’s simple division into great powers and all others was unrealistic and dangerous (Holbraad, 1984, p. 58). However, these suggestions were rejected, and non-permanent UNSC members are selected based on geography rather than function (ability to solve common problems). Nevertheless, most authors consider the UN’s creation to be when the concept of ‘middle power’ became a category of political practice.

There has already been some study of the concept’s history and definitions (Vershinina, 2020).

Some states do define themselves, directly or indirectly, as middle powers, and one approach would be to categorize as such any states that claim the label, studying the very “constructing of middlepowermanship” (de Bhal, 2023). Canada, Australia (Chapnick, 2005), and South Korea (Asmolov and Soloviev, 2021) are such “self-proclaimed” middle powers. However, “self-identification” can be unclear and changeable. Apart from Canada, Australia, and South Korea, Turkey, Mexico, and Indonesia once also identified themselves as middle powers of some sort (Robertson and Carr, 2023). However, the MIKTA group (Mexico, Indonesia, Korea, Turkey, Australia), established in 2013, is not described as an association of middle powers by its members, who prefer terms like ‘emerging regional actors’ (Davutoglu et al., 2014). And observers are themselves unsure whether middle, regional, or rising power is the appropriate term in this case (Shlykov, 2017). Additionally, self-identification potentially shrinks the cohort of middle powers to just two (Canada and Australia (Abbondanza and Wilkins, 2022)) or three (with South Korea (Vorontsov et al., 2020)).

As for the realist approach, it is hard enough to determine which states count as great powers, and even more difficult with middle powers, which overlap with the great powers at their ‘top’ and have an especially amorphous ‘bottom’. Furthermore, the top twenty or top thirty states in any national power index will fit the category of middle powers (Abbondanza and Wilkins, 2022). Brazil, Germany (Otte, 2000; Coticchia and Moro, 2020), and even India (Sethi, 1969; Efstathopoulos, 2011) have at different times been ranked as middle powers.

With realism largely focused on great power politics, middle powers received attention, in the last quarter of the 20th century, mainly from the liberal school of IR, which took a primarily normative approach. This permitted the study of international institutions through the behavior of their “ordinary” members. Additionally, since the middle powers of the time were liberal democracies, liberal IR theorists could draw conclusions about the effect of political regime on foreign policy.

Middle powers were identified as the ‘majority’ on which the liberal international order rested.

The “behavioral” definition suggests that middle powers tend to seek compromise and multilateral solutions, and to generally try to act in accordance with the ideal of ‘good international citizenship’ (a concept with no strict definition, used to “describe law-abiding and cooperative nations” (Abbondanza, 2021)). This definition also suggests that middle powers support American hegemony and the system of global institutions based on it (Cooper et al., 1993, pp. 19-20). That is, they make up the presumed (and sought) majority that “inhabits” the liberal international order. Based on the cases of Australia and Canada, they were also long assumed to have some international influence beyond their own regions (Carr, 2014). John de Bhal has wittily compared middle powers to the middle class, which appears particularly apt if the former is understood through its “behavioral” definition: the middle class has no clear definition, and the concept is instead deployed to reinforce status claims. Similarly, powers that cannot claim great-power status instead designate themselves as middle powers to separate themselves from minor states (de Bhal, 2023). Just as the middle class is often proclaimed a pillar of liberal democracy, middle powers are the mainstay of the liberal international order.

The “behavioral” definition of middle powers has many weaknesses. It is overly normative, based on very few cases, and simultaneously dependent upon excluding from the sample many illiberal states that, by their capabilities and influence, should qualify as middle powers, e.g., Iran. Hence attempts to add behavioral and domestic-political criteria to the definition. For instance, middle powers are defined as seeking “to weaken stratification where the great powers are concerned, and strengthen functional differentiation by taking on key roles in international politics” (Teo, 2022, p. 3). By gently counterbalancing the strongest players through international institutions and multilateral diplomacy, they look for niches where they can take leading roles (Cooper, 1997). Alternatively, “traditional” middle powers (established democracies with high levels of equality, for example, Australia, Canada, Sweden, and the Netherlands) are distinguished from “emerging” ones (recently established democracies with high levels of inequality) (Jordaan, 2003), in accordance with liberal IR’s inclination to link domestic political order to foreign policy. A similar approach identifies three “waves” of middle powers. First, Canada, Australia, and several others sought a special status in the UN in the mid-1940s. Second, the end of the Cold War saw the emergence of new middle powers (e.g., South Korea, South Africa, and Indonesia) and their increased activity. Third, the G20’s establishment provided institutional recognition of many middle powers, while also making the category even more heterogeneous (Cooper and Dal, 2017).

It is this heterogeneity that sometimes prompts calls to abandon the concept altogether. The crisis of the liberal international order also entails a crisis of its “citizenship”: middle powers, previously considered exemplary, become increasingly illiberal and disinclined to rely on international institutions and multilateral diplomacy (Robertson and Carr, 2023).

Although the United States declared a “unipolar moment” in the 1990s, many theorists and practitioners believed that the end of the Cold War opened up prospects not for American hegemony, but for strengthening multilateral international institutions, both governmental and nongovernmental. It was thought that the “growing complexity of global life is too great for any single country, or any condominium of countries, to acquire a hegemonic status comparable to those once held by the U.S. and Great Britain” (Rosenau, 1992, p. 292-293). The idea of “governance without government” emerged as the possibility of an international order without a single dominant center of power. It was assumed that globalization, agreement between the nuclear powers, and the near-universal adoption of “universal” liberal values would lay the foundation for a fundamentally new world order. Dieter Senghaas (1993) spoke of “world domestic policy” regarding the environment, development and poverty, and nuclear and conventional arms control. This ‘post-national paradigm’ (Brand, 2005) suggested that new centers of power (authority) were emerging at the transnational level (e.g., international NGOs) and subnational level (e.g., ethnic minority organizations), eroding the power and authority of nation-states (Rosenau, 1995).

Although theorists of the liberal world order distinguish it from American hegemony (Ikenberry, 2011), they, and the ‘post-national paradigm’, are functionally indistinguishable from Russia’s perspective based on the last few decades. Thus, the very concept of a middle power—per the liberal-constructivist ‘behavioral’ definition or per the realist power-based one—is a derivative of the international order and makes no sense without it.

Since World War II, middle powers have gone through two peaks of activity: immediately after the war (when the bipolar blocs had not yet crystallized, giving middle powers some freedom of action), and after the Cold War (when U.S. unipolarity led to the triumph of the liberal international order, supposedly a natural habitat for middle powers per their ‘behavioral’ definition) (Robertson and Carr, 2023). But what if we look at these two historical moments—the mid-1940s and the early 1990s—not from a realist perspective (what the great powers did), but from a systemic and institutional one (what the international order was like)? Both periods saw the (re)formation of the international order, which is apparently when middle powers are most audible and active.

1945, 1991, 2022?

In February 2022, the Ukraine crisis went from regional to global, giving a renewed urgency to the question of its implications for world order. Some believe that the year 2022 will become a landmark date in the history of international relations along with 1648, 1815, 1919, 1945, and 1989 (Flockhart and Korosteleva, 2022). Yet those dates mark the ends, not the beginnings, of conflicts, while the SMO’s end-date is unknown. Conversely, some Chinese authors believe that the treatment of a European (i.e., regional) crisis as global reflects the legacy of Eurocentrism (Jiemian, 2022). Nevertheless, anti-Russian sanctions have had global economic ramifications.

There is also no consensus about the implications of the crisis.

Many early Western reactions were triumphalist: democracies had closed their ranks against the Russian threat, and the liberal international order would emerge stronger than ever (Way, 2022). But there were also warnings that the West was facing its last chance to preserve the current order (Daalder and Lindsay, 2022). And others declared that 24 February 2022 had finally buried the liberal international order as a universal project, ushering in a “multi-order” world (Flockhart and Korosteleva, 2022) in which globalization is split into liberal and illiberal, roughly western and eastern (Benedikter, 2023). The notion of ‘American imperialism,’ against which Russia is now fighting (Artner, 2023), has also regained popularity.

We, however, are interested mainly in the motives of the World Majority, the Global South. Western authors mostly recognize that developing countries have serious reasons to not take either side (Spektor, 2023). “The Global South countries (except those with security ties with the U.S.) do not think that their ontological security is substantively affected by the war in Ukraine. They have voiced disquiet at the Global North’s attempts to embroil them in a struggle not of their making and which reproduces their subaltern status” (Krickovic and Sakwa, 2022). Refusing to be drawn into the Russo-Western confrontation, the Global South is also in no hurry to exit the liberal world order’s institutions (Schirm, 2023). However, the liberal world order promised peace but failed to secure it, and is now being replaced by a “multiplex” world order without a hegemon (we will return to this concept below) (Acharya, 2023). In this “non-polar” world, military power and war may no longer produce strategic results, order is based on the interdependence of many small elements, and power and security stem from consensus and legitimacy (Adib-Moghaddam, 2022). Notably, this pacifistic text (atypical of the times) was published in Pakistan, a clear middle power and a country of the World Majority, but without a dominant position in its region.

Several points stand out here.

Firstly, musings about the emerging world order are generally in line with the pre-2022 discussion. The crisis of the liberal international order has been acknowledged before, although there are different opinions about how it started (Ikenberry, 2018) and whether it is terminal. Mearsheimer (2019) advocates for two coexisting orders, American and Chinese, and insists that the liberal order cannot be made universal. His view of it, as including only the U.S. and its liberal democratic allies, is shared by Amitav Acharya, who describes the “multiplex world” as a movie theater with different screens of different sizes playing different films. However, this describes discursive, not political or institutional, multipolarity: within a single security and economic architecture, different “authors” tell different stories (Acharya, 2014).

Secondly, everyone agrees that the world is constructing a new order, or at least overhauling the old one. Some also claim that the new world order is already here, and conflicts and contradictions are its essential feature (Safranchuk and Lukyanov, 2021). Political, ideological, and institutional diversity has increased and plays an even greater role in shaping the international order. The West’s “self-isolation” is caused partly by the long crisis of the liberal order, and partly by the West’s failed attempt to draw the Global South into confrontation with Russia.

Thirdly, whatever the world order may be, many more actors are involved in shaping it than in the mid-1940s or the early 1990s. In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in non-Western histories of international relations and in non-Western international orders (Zhang, 2015), e.g., international orders in 13th-17th-century Eurasia that claimed universality (Zarakol, 2022). World-order theories based entirely on European history have come under heavy criticism (Acharya, 2014, p. 11).

What changed in recent decades? Barry Buzan and George Lawson recently argued (2015) that IR theory has barely noticed a problem central to other social sciences: How did modernity come about, and what is it? IR experts, and particularly realists, talk about world politics as if its participants and their relationships have not fundamentally changed since the time of Thucydides. They see Westphalia (1648) as the beginning of modern international relations, but ignore the emergence, in the 19th century, of a new “mode of power” associated with industrial capitalism, the rational bureaucratic state, and ideologies of progress such as liberalism, socialism, nationalism, and ‘scientific’ racism. In the 19th and 20th centuries, masters of this novel mode of power gained an enormous advantage, securing the West’s global hegemony and dividing the world into center and periphery.[5] By the beginning of the 21st century, the new mode of power had been mastered by nearly all countries, capitalism had become universal (albeit in different forms), and the only remaining ideologies of progress were liberalism and nationalism. Based on this, Buzan and Lawson draw a rather optimistic picture of the emerging world order, in which geopolitical rivalry between states will give way to geo-economic competition (according to Edward Luttwak), and global hegemony will become impossible, although regional hegemonies (e.g., of Russia or China) cannot be ruled out. Since global markets require some universality and internationality, all players will be interested in preserving the general rules of the game in at least some areas (Buzan and Lawson, 2015, pp. 290-293).

Perhaps they are overly optimistic. The two world wars were caused, inter alia, by the struggle for markets and economic resources. While violence within the Western liberal order is made redundant by the hegemony of the U.S. (which, e.g., nonviolently suppressed Japan’s economic rivalry in the 1980s), this will not work with China. The tsunami of sanctions against Russia and others has raised doubts that global markets are of such constant value to international players. While the nationalism of most countries (and almost all middle powers) is not universalistic, liberalism (like socialism) is, as proclaimed by rainbow flags on American embassies around the world. And it is unclear what to do if regional hegemonies overlap or if one state claims hegemony in multiple regions.

But, regardless, the world’s sharp division into center and periphery is shrinking.

More actors will build a new international order than ever before. This means that middle powers will once again come to the fore.

How to Construct the World Majority?

Bruno Latour (2007, pp. 88-91) has keenly observed that social scientists tend to use constructed as a synonym for artificial. “To say that something was ‘constructed’ in their minds meant that something was not true,” he wrote. But “in all domains, to say that something is constructed has always been associated with an appreciation of its robustness, quality, style, durability, worth, etc. … Everywhere, in technology, engineering, architecture, and art, construction is so much a synonym for the real that the question shifts immediately to the next and really interesting one: Is it well or badly constructed?”

In this sense, the World Majority is well constructed. It meets Russia’s current foreign policy needs and grasps the current moment in world history with as much certainty as possible. The concept captures the main phenomenon of the international system: the circle of powers that can (and apparently will) participate in shaping the new order has expanded dramatically. Although the countries of the World Majority (excepting Russia) do not themselves use the term, this paradoxically indicates that they take it seriously. Naming is an exercise of power, and acceptance of a name recognizes the power of its giver—but no one is eager to recognize external power nowadays. Hence the dwindling number of self-described middle powers: if you are a middle power, then there is someone else above you.

However, the World Majority lacks agency and substance. So far, it is defined for the most part negatively: “those who do not… (“impose sanctions against Russia, recognize American dominance, etc.”). The concept of new middle powers as creators of the international order can solve this problem. The liberal metaphor of “good international citizens” can also be helpful here.

The new middle powers are the good citizens of the World Majority. As in the case of liberal ‘international citizenship,’ this does not mean that only they are: the World Majority also includes great powers or near-great-powers such as China, India, Russia, and Brazil.

The liberal normative connotations of ‘citizenship’ will have to be dropped. A citizen of the World Majority highly values sovereignty, its own role in the world, and economic and technological development—but is definitely not a liberal. Yet normative connotations of citizenship with democracy can be added, as the growing number of participants in shaping the international order constitutes its democratization. A citizen rejects hegemony in favor of sovereign equality.

World Majority citizenship does not fundamentally exclude liberal international citizenship. Many countries are still interested in open markets and therefore in preserving the liberal international order that provides them. But liberal international citizenship is losing its inclusiveness. The “operators” of the liberal international order banish whomever they think does not belong. In the future, the World Majority’s citizens will have to determine whether liberal economic institutions are possible in an illiberal international environment.

It should be emphasized that citizenship in the World Majority does not mean status as a regional power. Many new middle powers are not dominant in their regions, regions’ definitions are politically determined, and the focus here is on the global international order.

The new middle powers are clearly interested in global institution-building, as evidenced by the recent expansions of the SCO and BRICS.

If Buzan and Lawson are right that the radical inequality in capabilities between the West and the Rest, which developed in the 19th century, is becoming a thing of the past, then the heretofore existing hierarchy of states may be ending along with it. Moreover, the power of a state depends on the domain in which it is being tested, and technological, economic, and demographic shifts are rapidly changing the list of potential claimants to great power status. The Valdai International Discussion Club’s annual reports speak of “a world without superpowers” and “a future without hierarchy” (Barabanov et al., 2022; Barabanov et al., 2023).

Indeed, firstly, the gap between the great powers and all other states is not as large now as it was in the past. Secondly, the degree of “greatness” depends more on the international context in which the power and capabilities of each particular state are manifested (and tested). Thirdly, technological, economic, and demographic shifts in the world are rapidly changing the list of countries that can claim the status of great powers.

Realism’s power-based definition of middle power is becoming less relevant. Middle powers can act as great powers and vice versa, depending on the situation. The list of new middle powers is thus potentially unlimited, with World Majority citizenship open to anyone ready to accept it. However, members of blocs (the only currently existing one is that which is led by the U.S.), which diligently follow bloc discipline, exclude themselves from the list, as World Majority citizenship is granted on an “individual basis.”

This article was written with financial support from the Institute for International Studies at MGIMO University, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, Project 2025-04-06

References

[1] “The term ‘World Majority’ means a community of non-Western countries that have no binding relationships with the United States and the organizations it patronizes. This definition needs further clarification, but it can be used as a working option. The use of the term ‘Global Majority’ is undesirable, as it refers to the liberal globalization concept from the previous stage. (Karaganov et al., 2023). The concepts of the World Majority and the Global Majority were also used before to refer to the part of humanity that does not make up the Western minority, but they were used mainly in studies of social movements, education, and human rights, not of international relations (Doyle, 2005; Shepherd, 1987; Campbell-Stephens, 2021).

[2] Google queries for ‘world majority’ on website:narendramodi.in, and ‘world majority’ on website:narendramodi.in

[3] https://www.narendramodi.in/in-pictures-pm-modi-with-president-obama-in-india-7201

[4] Google query for ‘world majority’ on website: fmprc.gov.cn/rus/

[5] Despite similar terminology, Buzan and Lawson’s approach to center-periphery differs from Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-system theory, which traces the division back to the emergence of market exchange mechanisms and sees the positions of individual countries as highly stable.

____________

Abbondanza, G., 2018. The Historical Determination of the Middle Power Concept. In: T. Struye de Swielande, D. Vandamme, D. Walton, and T. Wilkins (eds.) Rethinking Middle Powers in the Asian Century. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 32-44.

Abbondanza, G., 2021. Australia the ‘Good International Citizen’? The Limits of a Traditional Middle Power. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 75 (2), pp. 178-96.

Abbondanza, G. and Wilkins, T. S., 2022. The Case for Awkward Powers. In: G. Abbondanza, G. and T.S. Wilkins (eds.). Awkward Powers: Escaping Traditional Great and Middle Power Theory. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 3-39.

Acharya, A.A., 2023. Multiplex World: The Coming World Order. In: M. Muqtedar Khan (ed.). Emerging World Order After the Russia-Ukraine War. Leading Thinkers Reflect on Post-War Global Power and Authority. New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, March. Available: https://anthologies.newlinesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/20230301-Anthology-Emerging-World-Order-NLISAP-1.pdf#page=8 [Accessed 17 August 2024].

Acharya, A., 2014. The End of American World Order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Adib-Moghaddam, A., 2022. World Politics after the War in Ukraine: Non-Polarity and Its South Asian Dimensions. Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) Journal, 22 (2), pp. 61-75.

Artner, A.A., 2023. New World Is Born: Russia’s Anti-Imperialist Fight in Ukraine. International Critical Thought, 13 (1), pp. 37-55.

Asmolov, K.V. and Soloviev, A. V., 2021. Strategicheskaya avtonomiya Respubliki Koreya: intellektualnaya khimera ili politicheskaya realnost’? [Strategic Autonomy for ROK: Intellectual Pipe Dream or Political Reality?] Journal of International Analytics, 12(2), pp. 49-73.

Barabanov, O., Bordachev, T., Lissovolik, Ya., Lukyanov, F., Sushentsov, A., Timofeev, I., 2022. A World Without Superpowers. The Annual Report of the Valdai Discussion Club, October. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/files/39600/ [Accessed 17 August 2024].

Barabanov, O., Bordachev, T., Lukyanov, F., Sushentsov, A., Timofeev, I. Maturity Certificate, or The Order That Never Was. Fantasy of a Hierarchy-Free Future. The Annual Report of the Valdai Discussion Club, October, 2023. Available at: https://valdaiclub.com/files/42478/ [Accessed 17 August 2024].

Benedikter, R., 2023. The New Global Direction: From “One Globalization” to “Two Globalizations”? Russia’s War in Ukraine in Global Perspective. New Global Studies, 17(1), pp. 71-104.

Bourdieu, P., 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press.

Brand, U., 2005. Order and Regulation: Global Governance as a Hegemonic Discourse of International Politics? Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), pp. 155-176.

Buzan B., and Lawson G., 2015. The Global Transformation: History, Modernity and the Making of International Relations. Cambridge University Press.

Campbell-Stephens, R.M., 2021. Educational Leadership and the Global Majority: Decolonising Narratives. Springer Nature.

Carr, A., 2014. Is Australia a Middle Power? A Systemic Impact Approach. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 68(1), pp. 70-84.

Chapnick, A., 2005. The Middle Power Project: Canada and the Founding of the United Nations. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Cooper, A.F., 1997. Niche Diplomacy: A Conceptual Overview. In: A.F. Cooper (ed.). Niche Diplomacy: Middle Powers after the Cold War. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-24.

Cooper, A.F., Higgott, R.A., and Nossal, K.R., 1993. Relocating Middle Powers: Australia and Canada in a Changing World Order. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Cooper, A.F. and Dal, E.P., 2017. Positioning the Third Wave of Middle Power Diplomacy: Institutional Elevation, Practice Limitations. Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis, 71(4), pp. 516-528.

Coticchia, F. and Moro, F. N., 2020. Aspiring and Reluctant Middle Powers? Italy’s and Germany’s Defense Reforms after the Cold War. In: G. Giacomello and B. Verbeek (eds.) Middle Powers in Asia and Europe in the 21st Century. Lexington Books, pp. 57-76.

Daalder, I.H. and Lindsay, J.M., 2022. Last Best Hope: The West’s Final Chance to Build a Better World Order. Foreign Affairs, 101.

Davutoglu, A., Bishop, J., Natalegawa, M., Meade, J. A., and Yun, B., 2014. MIKTA as a Force for Good. Daily Sabah, 25 April. Available at: https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/2014/04/25/mikta-as-a-force-for-good [Accessed 17 August 2024].

de Bhal, J., 2023. Rethinking ‘Middle Powers’ as a Category of Practice: Stratification, Ambiguity, and Power. International Theory, 15(3), pp. 404-427.

Doyle, T., 2005. Environmental Movements in Minority and Majority Worlds: A Global Perspective. Rutgers University Press.

Efstathopoulos, C., 2011. Reinterpreting India’s Rise through the Middle Power Prism. Asian Journal of Political Science, 19(1), pp. 74-95.

Flockhart, T. and Korosteleva, E. A., 2022. War in Ukraine: Putin and the Multi-Order World. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(3), pp. 466-481.

Holbraad, C., 1984. Middle Powers in International Politics. London: Macmillan Press.

Ikenberry, G.J., 2018. The End of Liberal International Order? International Affairs, 94(1), pp. 7-23.

Ikenberry, G.J., 2011. Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jiemian, Y., 2022. The Changing World Order and the Responsibilities of Developing Countries during the Ukraine Crisis. China International Studies, 95.

Jordaan, E., 2003. The Concept of a Middle Power in International Relations: Distinguishing between Emerging and Traditional Middle Powers. Politikon, 30(1), pp. 165-181.

Karaganov, S.A., Kramarenko, A.M., and Trenin, D.V., 2023. Politika Rossii v otnoshenii mirovogo bolshinstva [Russia’s Policy towards the World Majority]. Moscow: HSE University.

Krickovic, A. and Sakwa, R., 2022. War in Ukraine: The Clash of Norms and Ontologies. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 22(2), pp. 89-109.

Kupriyanov, A.V., 2021. Indo-Pasifika kak geopolitichesky konstrukt: podkhod Indii i interesy Rossii [Indo-Pacific as a Geopolitical Construct: India’s Approach and Russia’s Interests]. Mezhdunarodnaya zhizn’, 11 November, pp. 60-71.

Latour, B., 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mearsheimer, J.J., 2019. Bound to Fail. The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order. International Security, 43 (4), Spring, pp. 7-50.

MIKTA. What Is MIKTA? [online]. Available at: http://mikta.org/about/what-is-mikta/ [Accessed 17 August 2024].

Otte, M., 2000. A Rising Middle Power? German Foreign Policy in Transformation, 1988-1995. New York: St. Martin’s.

Robertson, J. and Carr, A., 2023. Is Anyone a Middle Power? The Case for Historicization. International Theory, 15(3), pp. 379-403.

Rosenau, J.N., 1992. Citizenship in a Changing Global Order. In: J.N. Rosenau and E.O. Czempiel (eds) Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 272-294.

Rosenau, J.N., 1995. Governance in the Twenty-First Century. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 1(1), pp. 13-43.

Safranchuk, I.A. and Lukyanov F.A., 2021. Sovremenny mirovoi poryadok: adaptatsiya aktorov k strukturnym realiyam [The Contemporary World Order: The Adaptation of Actors to Structural Realities]. Polis. Politicheskie issledovaniya, 4, pp. 14-25. DOI: 10.17976/jpps/2021.04.03

Schirm, S.A., 2023. Alternative World Orders? Russia’s Ukraine War and the Domestic Politics of the BRICS. The International Spectator, 58(3), pp. 55-73.

Senghaas, D., 1993. Global Governance: How Could It Be Conceived? Security Dialogue, 24(3), pp. 247-256.

Sethi, J.D., 1969. India as Middle Power. India Quarterly, 25(2), pp. 107-121.

Shepherd, G.W., 1987. Global Majority Rights: The African Context. Africa Today, 34(1/2), 1st Qtr – 2nd Qtr, pp. 13-26.

Shlykov, P.V., 2017. Poisk transregionalnykh alternativ v Evrazii: fenomen MIKTA [In Search for Transregional Alternatives in Eurasia: The Phenomenon of MIKTA]. Comparative Politics Russia, 4, pp. 127-144.

Spektor, M., 2023. In Defense of the Fence Sitters: What the West Gets Wrong about Hedging. Foreign Affairs, 102.

Teo, S., 2022. Toward a Differentiation-Based Framework for Middle Power Behavior. International Theory, 14(1), pp 1-24.

Tsygankov, P.A., 2013. Sistemny podkhod v teorii mezhdunarodnykh otnosheniy [Systemic Approach in the International Relations Theory]. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta, Seriya 12, Politicheskie nauki, 5, pp. 3-25.

Vershinina, V.V., 2020. “Derzhavy srednego urovnya” v mezhdunarodnykh otnosheniyakh: sravnitelny analiz kontseptualnykh podkhodov [Middle Powers in International Relations: Comparative Analysis of Conceptual Approaches]. Comparative Politics Russia, 3, pp. 25-40.

Vorontsov, A., Ponka, T., and Varpahovskis, E., 2020. Kontseptsiya “srednei sily” (Middle Power) vo vneshnei politike Respubliki Koreya [Middlepowermanship in Korean Foreign Policy]. Mezhdunarodnye protsessy, 18(1), pp. 89-105.

Way, L.A., 2022. The Rebirth of the Liberal World Order? Journal of Democracy, 33(2), pp. 5-17.

Zarakol, A., 2022. Before the West: The Rise and Fall of Eastern World Orders. Cambridge University Press.

Zhang, F., 2015. Chinese Hegemony: Grand Strategy and International Institutions in East Asian History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

By Russia in Global Affairs | Created at 2024-10-29 18:21:54 | Updated at 2024-10-30 05:27:45

4 weeks ago

By Russia in Global Affairs | Created at 2024-10-29 18:21:54 | Updated at 2024-10-30 05:27:45

4 weeks ago