Nasa is developing tiny swimming robots designed to explore the vast underwater oceans beneath the icy surface of Jupiter's moon Europa.

The innovative project aims to search for potential signs of life in the moon's subsurface waters, which are believed to contain more liquid water than all of Earth's oceans combined.

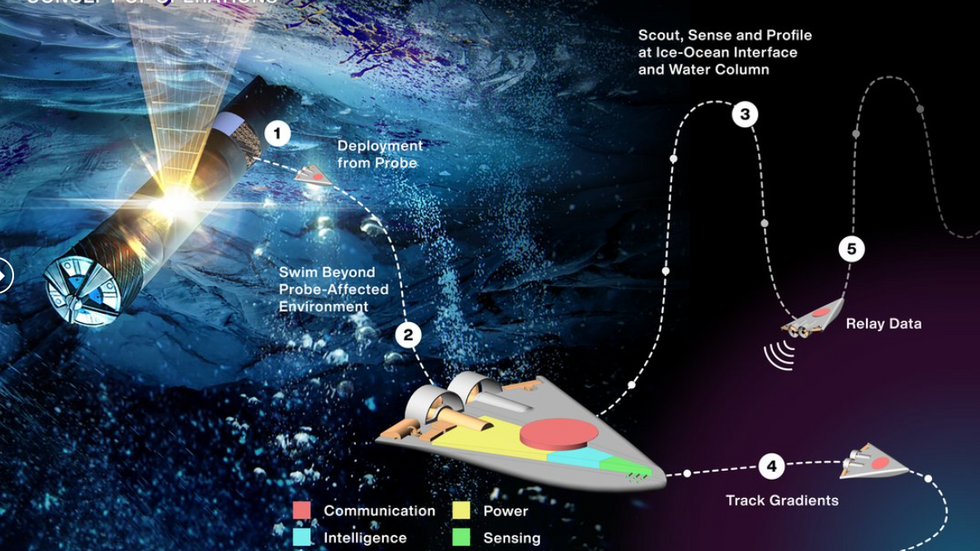

The robots would be delivered through Europa's 10-mile thick ice shell via a nuclear-powered thermal drill, creating a tunnel to access the liquid ocean below.

"People might ask, why is Nasa developing an underwater robot for space exploration?" said Dr Ethan Schaler, principal investigator at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in southern California.

The robots would be delivered through Europa's 10-mile thick ice shell via a nuclear-powered thermal drill

NASA

Dr Schaler believes a swarm of small swimming robots would explore more ocean water than traditional single large probes.

The project, named Sensing with Independent Micro-swimmers (Swim), has received $725,000 in Nasa funding.

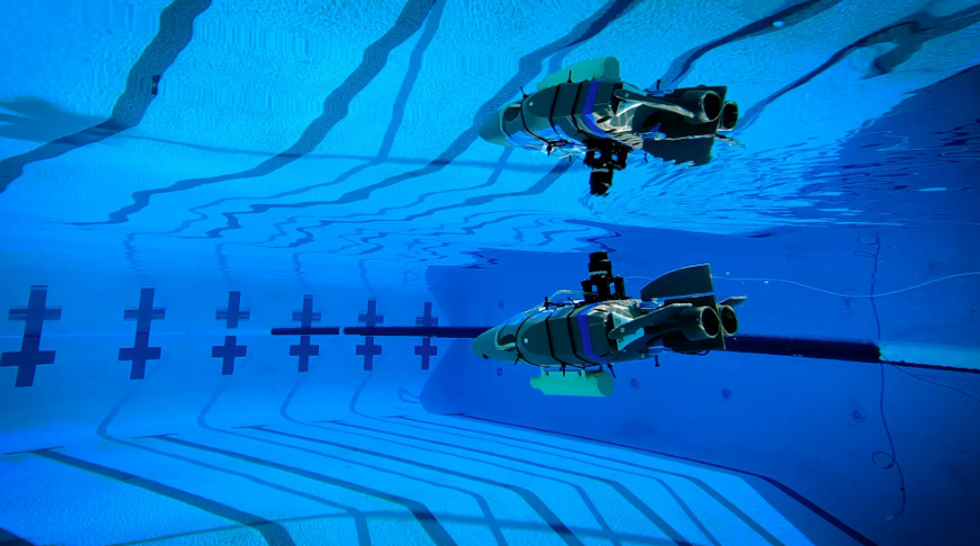

Current prototype testing in a swimming pool at Caltech university is showing encouraging results.

The initial wedge-shaped robots, made from 3D printed plastic, have demonstrated good manoeuvrability and autonomous navigation.

The current prototypes measure 16.5 inches (42cm) in length and weigh about five pounds (2.3kg).

Engineers aim to reduce their size by two-thirds, making them roughly the size of a mobile phone.

The robots would communicate underwater using a sonar-like system to send data back to the cryobot drill.

The cryobot would then relay information through the ice to a lander on Europa's surface, which would transmit the data back to Earth.

The swim-bots would operate for approximately two hours on battery power

NASA

"The robots would be stowed within the streamlined body during the descent through the ice, and the micro-swimmers would be deployed individually or as a swarm from the cryobot," explained Dr Schaler.

About four dozen robots could fit inside a 10-inch diameter section of the thermal drill.

The swim-bots would operate for approximately two hours on battery power.

Computer simulations show they could explore around three million cubic feet during their operational lifetime.

The swim-bots would carry a specialised chip designed by Georgia Tech university.

This chip would measure temperature, pressure, acidity or alkalinity, conductivity and chemical makeup of the ocean waters.

"There are many challenges with realising a concept like this," noted Dr Schaler.

"On Europa, the robots would be swimming in a saltwater ocean under high pressure. These are factors that would be accounted for in a final design," he added.

The team is awaiting data from NASA's Europa Clipper mission, launched in October.

The spacecraft will reach Europa in 2030, beginning 49 flybys to assess if the moon could harbour life.

The European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer spacecraft, launched last year, will arrive in 2034.

If these missions find suitable conditions for life, the swim-bot project could receive approval to proceed.

"I'm excited to see what we discover about Europa from Nasa's Europa Clipper and ESA's Juice spacecraft in 2030 and beyond," said Dr Schaler.

By GB News (World News) | Created at 2024-12-28 20:04:17 | Updated at 2024-12-29 12:04:40

16 hours ago

By GB News (World News) | Created at 2024-12-28 20:04:17 | Updated at 2024-12-29 12:04:40

16 hours ago