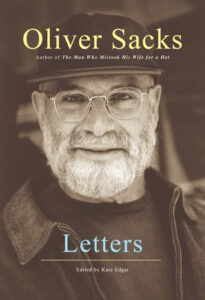

July 7, 1973 Article continues after advertisement Dear Thom, You are often in my thoughts, and I am always meaning to write to you—but—so little is translated into action. I fear I never thanked you for your poetic New Year’s card—although it resides permanently on my mantelpiece. I gather (from Faber’s) that you have changed your address; but I can only visualize you in the surroundings of Filbert. I have asked my publisher to send you a copy of my (so-long-obstructed-and-delayed) new book Awakenings—I hope it has arrived, or will do so shortly. First reactions, here, have been very kind. But, fortunately or unfortunately, my mind is so fixed on the next book, the real one—it will be, I think, a very general one, which I shall call “Station and Motion”—that Awakenings, and reactions to it, do not seem quite real. I have also been pondering about pain—Faber’s have asked me if I would write about it for them (but I fear it would become a theological book); do you remember how we once talked of pain?—it must have been ten or a dozen years ago. Time: Time the preserver, time the destroyer—I shall be 40 in two day’s time. It doesn’t upset me as I once thought it would; I suppose I have found the last 5 years easier and pleasanter than the years of often almost hopeless neurosis which preceded them. On the whole now, though it comes and goes, I have a lovely feeling of movement and change, and a preparedness for change whatever it entails: “Respondeo etsi mutabor.” The years of neurosis were years of transfixion, of an absolute terror and incapacity for change. Article continues after advertisement Time. These last few days I have had the strangest rush of ancient memories (some, perhaps, phantasies), most dating from my earliest childhood (’35, ’36). I find the old Broad St. train (which I take every day to the Heath) is like a catalyst, a releaser, a Proustian mnemonic; it has become a memory train, conveying me back into the mid 1930’s; and if ever I try my hand at an autobiography, I will use it as this, as a train back to childhood. Images of home, of journeys, seem to occupy me constantly now (I must try to dig up “Travel Happy,” that one piece of my former writing you felt was—real). The need for travel, for some sort of pilgrimage (the nature of which will become clear only later) is very intense: I may be going to Italy for a while: two summers ago, I was immensely moved by Goethe’s Italian Journey, and last summer by Lawrence’s Italy-books, (especially Etruscan Places, which you mentioned to me in 1960, I think)—And this summer, perhaps, I shall have my own Italian Journey. Do write, Thom, and tell me something of yourself and your plans—and, in particular, whether you have any thoughts of England or New York this year. Yours, Article continues after advertisement November 29, 1973 Dear Thom, I was most affected by your letter of—almost two months ago; I appreciated it—its feeling and thought and care—more, I think, than any other letter anyone has written me about Awakenings; and if I have been slow in answering (and if this answer is laboured or stilted), it is not because I have been unmindful or ungrateful for your letter, but, rather, that it obsessed me in a way, and gave rise to such a range of reflection and retrospection, and such conflict, that I wasn’t sure how to write back. First, I thank you for your sympathy about Wystan’s death, and I feel too the loss this must be to you, and so many others. I originally met him four or five years ago, and we approached each other very slowly as people—we were both intensely shy in a way. In the past year he had become very dear to me—I really came to love him in all sorts of ways. In particular he stood for trust, an immense solidity and substance and depth, with a beautiful candour and transparency: so that the impulse to lie or distort or conceal or falsify (etc.) went away in his presence, and in some fundamental way he taught me how to be myself, by being himself. You speculate as to what has happened to/with me, what has brought out some sort of humanity or sympathy which seemed absent or dormant in the early sixties. It has been a slow process, and God knows one fraught with the continual danger of lapses and regressions—when something hateful takes possession of me, and I again find myself writing (though not acting out) things and situations of the “Doctor Kindly” genre. You are surely right when you say that one cannot be taught sympathy, humanity, etc—in the sense that it is not amenable to injection, instructional instillation, etc. I always had a sort of empathic passion for “Nature,” but, bye and large, it was a “Nature” which more or less excluded human beings. I could feel at ease with a theorem, or a poem, or a landscape, but almost never with a person, and almost never with myself. I think this has changed a good deal over the past few years, but I really don’t know what have been the chief determinants. I have found working and loving increasingly synonymous; I cannot understand anything, I cannot approach it intellectually, except as a relation, in a sort of devotion or intimacy; and I had the blessing of a marvellous group of patients, who were at once as singular as the fauna of the Galapagos, and yet intensely real to me as human beings; I think they made a decisive difference to me, as (perhaps) I did to them: and this, in a way, has been a sort of love-affair. The two individuals who have meant most to me in the last five years have been my analyst—and Wystan, among the “living living”; they have stood for trust, and love, or at least the sense of the possibility of these, in a way I could scarcely have imagined five or six years ago. These, and the “living dead,” the voices and teachers from the past, who have spoken to my condition, who have induced and carried me through various crises, and who have felt so palpably present, at times, as to give me an almost physical joy and warmth. There have been a dozen or more such teachers, out of the past: and the one who has most moved me, who has seemed to me richest in reality and suggestion and aesthetic delight, has been Leibniz, who I “discovered” in April of last year. It is odd, I found I had read quite [a lot] of him twenty years ago, as a student, but had “forgotten” it all; it left no impact; I wasn’t ready; and then suddenly—indeed it was sudden, like a revelation, at 4.30 on April 18 of last year!—I “remembered” him again, and plunged back with a sense of continually-growing delight and awareness, and above all, that lovely sense of recapturing the past, one’s past, the human past, my childhood—a sort of marvellous Platonic anamnesis. I have suffered very much from losing the past, losing my childhood; I have, unlike you, lacked continuity and roots in this absolutely fundamental sort of way; it has given rise to all sorts of nostalgias, genuine and phoney (drugs, on the whole, seemed to me—or at least the way I used them, which was mischievous and narcissistic, to give me only a phoney past, a regression, instead of the awareness and continuity I sought); but various people—patients, students, friends, Wystan, and my analyst—have helped me to recover some of what I had thought to be irredeemably lost, and to become—if only intermittently—a real person. Article continues after advertisement But no, alas!, there has been no “falling in love” with anyone, in the more literal sense, in the sense of a deep mutuality and respect and wish to share, etc; my “infatuations” and fatuous fetishes etc. have grown weaker, and less satisfactory as love-substitutes, as substitutes for anything; but they have left something of a vacuum, erotic, spiritual, or whatever; and I often feel intensely and genuinely lonely now in a way in which I never used to. I would love to love and be loved, and have a lover, and be a lover; but I am very isolated, I see very few people, and perhaps (ironically, now I am perhaps mature enough to maintain such a relation) I am now too old. At least I feel painfully old, at the moment; I have since the death of my mother, last November. […] I’m sorry—this is a rambling, and maybe very egotistical sort of letter. As I said at the start, I have not known how to reply. When you criticized my writing (and, by implication, I felt, me) a dozen years ago, I used to feel annihilated—incidentally, I think I did write a few decent things (like “Travel Happy”); it was not all virulent or phoney like “Doctor Kindly”—and now you express appreciation of Awakenings, it gives me immense pleasure, and a sense and sort of existing (which I lose all too easily). I have been thinking of going to the West Coast for a few days around Xmas–New Year: will you be around then? I would love to see you—and, again, many many thanks for your exact and generous letter. Love, PS: I think—indeed I am sure—you are wrong about Wystan not liking you. The two of you had not met too often—and, as I say, personal feelings were slow to grow and mature in him. But I know that he liked and admired your poetry immensely: after meeting you last summer (was it a poetry reading?) he said, “Thom writes magnificently—but he does dress very strangely!” Article continues after advertisement December 31, 1973 Dear Thom, Thank you for your friendly postcard—I much appreciated it, having felt that I had sent you a letter somehow wrong. Indeed I continue to feel somewhat obsessed by your letter (which I tend to carry with me), and have the increasing feeling that my own—like, perhaps, so many of my own writings and feelings—was less than candid, if not positively disingenuous; wanting in candour, in penetration, and perhaps too in that sort of sympathy and humanity which unites me so naturally to my patients and students, but which I find so hard to extend to my friends (or myself). Other things make me think of you. It is a marvellous morning, of a sort one remembers from childhood, but which seems to be exceedingly rare, these days, in London: an utterly clear and cloudless sky, low low December sun, everything frosty, intense, alive, bathed in a lucid, almost Arctic sort of sunlight—the sort of sunlight which reminds me of “Sunlight”—sharp, unsparing, yet extraordinarily gentle. And yesterday (in the train, coming back from the North) I reread Etruscan Places, and that made me think of you—I remember how warmly you spoke of it soon after we met. And (it being a bit below freezing) I have on my favourite (now rather ancient) leather jacket and mittens, in which the fetish is sublimated into proper role and friendly presence; and sitting in the garden, in the frost, in the sunlight, mitted and kitted up to my eyebrows—this also makes me think of you, what we share and variously apprehend, and of my dismissive dishonesty, in my previous letter, in speaking of “fatuous fetishes” as something behind me, done-away-with, forgotten. What a complex business, these “emblems of identity.” Easy to be overcome and infatuated; easy to be dismissive and sneering; but so difficult to prehend or present in its full complexity (and full simplicity), without reduction or caricature. I cannot pretend to understand—although I understand enough to see the partial folly (and the partial truth) of earlier feelings, earlier writings. You, I think, always had a humour, an irony, an art—the power of detachment, of simultaneously being and seeing—being both inside and outside a certain frame-of-reference. This is, in effect, what you said to me the first time we met, viz. “I am me—not my parents, or the subject of my poems. You mustn’t confuse the writer and his subject”—or something of the sort. You always had, I suspect, this amalgam of genuine feeling from the “inside” with an artistic seeing from the “outside,” a humorous mastery which prevented any sort of total identification or engulfment: the doubleness which transforms one from passive (pulsive) to active, patient to agent, victim to—I don’t know how to say it, but a sort of mastery, without doubt. It is the sort of doubleness which I try to encourage in the patients I see, and which my analyst tries to encourage in me, in which one is both inside and outside the state of “patienthood” (forgive horrid word!), inside and outside what one suffers, and is; so that one is not dominated and devoured by a part of oneself. I lacked that sort of doubleness, detachment, humour, mastery, for many years; doubtless (though less) the lack is still there. There was a sort of ferocity and totality of identification (with some fierce, fantastic, impregnable “Wolfhood,” as opposed to what I felt as my soft, unformed, vulnerable Oliverity!), which at once promised identity and a loss of identity, a sort of enthralling (and fatal) death and rebirth. Perhaps I gave way to such ideas especially between ’63 and ’67, after I had left San Francisco (and relative sanity), and moved into a labyrinth, a mire, of phantastica and drugs. I cannot tell you (though there is no need) the intensity of lostness and foundness (but a false “foundness”) I traversed in those years. Nor can I assess, as yet (if ever it will be possible) the contribution of those years of almost-total immersion in drugs and phantasies to what I am now, or to be in the future. To call them “regressive,” to write them off, to disown them, to deny them—as perhaps I tended to do in my previous letter—is certainly a foolish reduction and fraud, and I feel ashamed of the dismissiveness, or contempt, which I may have expressed. But you will understand better, and forgive, if I make clear to you the degree of engulfment which I have been through in the past (and which, perhaps, in varied forms, perpetually faces me). It is a sensitive area for both of us, complex, exciting, dodgy, as any. The relation of one’s poses and postures and “pseudo” identity to one’s “real” and constant, ever-growing richly-aspectual identity is far beyond my understanding at the moment: clearly, one’s identity is in no sense simply the sum of one’s identifications; but nor is it something pure and Platonic, or completely transcendent. Auden (like the Red Queen) used to say, “Always remember who you are.” And I think he had a very good idea of who (what, why) he was. My idea of self is much fainter (or given to vanishing) and more clouded with conflicts and contradictory identifications. And yet, it is (or is it?) (at least some of) these very conflicts which provide the possibility of fruitful reconciliations and renewals in oneself. __________________________________ From Letters by Oliver Sacks, edited by Kate Edgar. Copyright © 2024. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

37 Mapesbury Rd., London

Oliver

11 Central Parkway, Mt. Vernon, NY

Oliver

37 Mapesbury Rd., London

By Literary Hub | Created at 2024-11-18 10:10:57 | Updated at 2024-11-21 13:55:56

3 days ago

By Literary Hub | Created at 2024-11-18 10:10:57 | Updated at 2024-11-21 13:55:56

3 days ago