Continued from Part I.

In the 1960s, outside pressure and even internal criticism built up against the church. Some universities, such as Stanford, refused to compete with the Mormons’ Brigham Young University until it changed its stance. The church resisted throughout the sixties.

BYU campus in the 1960s.

Privately, David O. McKay, who at that time was the successor of Joseph Smith as president of the Church, admitted that he was getting tired of criticism. He said that if he felt that God authorized such a change, he would be willing to implement it, even though he found intermarriage repugnant.

McKay died in 1970, and by the late 1970s, the LDS organization was becoming global. Despite the restrictions on those with “colored blood,” the church saw growth in places such as Africa, the Caribbean, and Brazil. Brazil was a tough case because it had a long history of miscegenation.

Mormon converts Wynetta Willis Martin Clark (left) and Marilyn Yuille joined the Tabernacle Choir in 1969 and 1970. They were its first black members.

Some say the Church gave in to peer pressure and lifted the restriction. The official explanation is that after extended prayer and fasting, Spencer Kimball, then-president of the Church, decided that God gave divine authorization to lift the restriction.

When it was lifted, the Church never apologized for its previous stance, and never denied that the prior restriction on “Negros” was divinely instituted. Many of the Church’s respected theologians still taught that race wasn’t inconsequential; the only difference was that the time had come to let blacks participate in priestly offices.

The church claimed that the change was similar to the New Testament precedent in Acts, in which, only after the resurrection did Jesus direct his disciples no longer to exclude Gentiles from the gospel but to preach to everyone. During his lifetime, he preached only to Jews. In Matthew 15:24, when a Canaanite woman asks him to heal her daughter, he answers, “I am not sent but unto the lost sheep of the house of Israel.”

As for Mormons, even after lifting the restrictions on the priesthood, there were warnings against interracial dating or marriage. This was discouraged even as late as the early 2000s.

At present, there is very little official literature or statements on race. What little there is, aligns with conventional views.

In 2012, Mitt Romney was the GOP nominee for president against Barack Obama, America’s first black president. Many Christians hold unfavorable views toward Mormons — not because of their past racial views, but for theological reasons. However, the faith’s historical views became an issue.

A Washington Post reporter flew to Salt Lake City and went to the BYU campus and interviewed religion department Prof. Randy Bott:

“God has always been discriminatory when it comes to whom he grants the authority of the priesthood,” says Bott, the BYU theologian. He quotes Mormon scripture that states that the Lord gives to people ‘all that he seeth fit.’ Bott compares Blacks with a young child prematurely asking for the keys to her father’s car and explains that, similarly, until 1978, the Lord determined that Blacks were not yet ready for the priesthood.

“What is discrimination?” Bott asks. “I think that is keeping something from somebody that would be a benefit for them, right? But what if it wouldn’t have been a benefit to them?” Bott says that the denial of the priesthood to Blacks on Earth — although not in the afterlife — protected them from the lowest rungs of hell reserved for people who abuse their priesthood powers. “You couldn’t fall off the top of the ladder because you weren’t on the top of the ladder. So, in reality, the Blacks not having the priesthood was the greatest blessing God could give them.”

This panicked the Church’s public relations department. It said that while it was true there was a prior temporary restriction on priesthood offices for blacks, the theories and views of the professor did not reflect official doctrine, and that the Church was against all forms of racism. Not long after, Professor Bott announced his retirement and intent to pursue a Church mission with his wife.

The Church then published an essay, which was part of a wider series dealing with the history of the racial restriction. There was no single author listed; it was a collaboration. Some strongly believed the restriction never had divine origins, while others believed there were divine origins, but that it was merely a matter of political expediency for the Church during a time of racial tension within the nation.

It explains the origin, history, and nature of the restriction, but doesn’t address any of the actual canonical scripture passages that deal with it. My own view is that it was a good attempt to phrase things in a vague way so that anyone who read it could interpret it however he wanted.

At the end, the essay lists various assertions, such as dark skin being a divine curse or that mixed-race marriage was a sin, both of which the Church disavowed as not official doctrine. Initially, many progressives saw this as an apology. However, I see it as a well-crafted public relations statement meant to silence critics and pacify progressive members. Despite the disavowal, the Church did not retract any passages of scripture or even repudiate books written by earlier leaders that supported the restrictions.

On June 1, 2018, the Church marked the 40th anniversary of the lifting of the restriction, in something called the “Be One Celebration.” The Church recruited black members from congregations throughout the world to sing, reenact stories of black converts, and celebrate black heritage.

The 2018 LDS “Be One Celebration.”

Dallin H. Oaks, who is part of a presiding quorum in the Church known as the First Presidency, was the keynote speaker. Many expected a formal public apology, but in a move of surprising boldness, he reaffirmed that the restriction was from God, but that sometimes we don’t understand all His reasons. He concluded by saying, essentially, let’s just let the past be the past. Critics thought he betrayed the entire celebration.

Each year, the Church publishes a curriculum to be taught in Sunday School and at home, with passages from the Book of Mormon to be studied each Sunday. It was probably just bad luck, but in February 2020 — “Black History Month” — Mormons were to study the verses about Indians being cursed with dark skin as a way to separate them from whites. It included a quote from a prior Church president explaining that dark skin was a mark set upon the ancestors of the Indians but also explained that Indians who joined the Church were no longer cursed and no longer separated from God.

Many members felt this was a major step backward and were worried this would resurrect old prejudices. The public relations department issued another statement that the Church was not racist and rewrote the curriculum. The new version included a vague statement that “the nature of the mark [on Indians] is not fully understood.”

Many progressive Church members began to argue that dark skin was not meant to be taken literally but was an ancient idiom referring to spiritual darkness. That same year, Gary E. Stevenson, a member of the presiding quorum, was invited to attend a Salt Lake NAACP breakfast, where he said the published manual was an unfortunate error and that he was sorry for the sadness it apparently caused. Later in 2020, during the George Floyd protests, the Church made vague statements about the need for civility and tolerance across racial lines.

Mormons are said to dominate Utah, but there may be only 45 to 50 percent who are real believers. Media and many state-run universities are bastions of progressivism, and combat the Church’s stance on “sexual minorities,” which is often compared to what it used to say about blacks.

In 2020, a statue of Brigham Young on the BYU campus was defaced with “racist” in red paint.

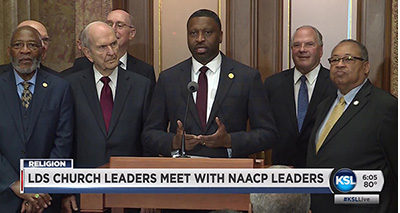

The Church made a partnership with the NAACP and pledged five million dollars for scholarships and humanitarian assistance. Traditional conservative members were perplexed, not so much because of race, but because the NAACP backs progressive causes that are antithetical to Mormon doctrines. Conservatives don’t like LGBT ideology, abortion rights, new ideas of sex roles, and sympathy for what many Mormons consider socialism.

As part of the partnership, the Church rolled out the red carpet for NAACP leaders, even flying some of them to Ghana to show them the new LDS missionary training facilities. The Church took pictures of NAACP bigwigs touring the facility and Mormon places of worship.

According to someone who worked for the church, it didn’t get the praise it hoped for. In LDS artwork, Jesus, angels, and God are often depicted as white men. NAACP representatives didn’t like that.

In LDS art, divine beings as almost always white. Here, a Guardian Angel guides a child.

The Salt Lake Tribune interviewed members of the NAACP to get their impression of the collaboration. Needless to say, the Church had not done nearly enough. Will Colom, special counsel to the NAACP said he was:

looking forward to the church doing more to undo the 150 years of damage they did by how they treated African Americans in the church and by their endorsement of how African Americans were treated throughout the country, including segregation and Jim Crow laws.

He said there seemed to be no willingness on the part of the Church to do anything material, and he looked forward “to their deeds matching their words.” “It’s time now for more than sweet talk.”

Even within the Church, there seems to be a big divide on how to approach racially inconvenient teachings. Many progressives argue that the racial teachings were never divinely sanctioned but were “false traditions” that sprang from the racially charged environment of the time. They want the Church to adopt social justice and anti-racism.

Black members are especially vocal, but some Hispanic and Indian members also object to the idea that they inherited certain physical distinctions from their ancestors. The Church of Latter-day Saints is going through growing pains as it tries to make its faith more globally palatable, and critics will not be satisfied by anything less than a full retraction of key passages.

Interestingly, the Church released a new publication last week regarding its stance on race, included in the “Topics and Questions” section. It’s clear that much of the content was drawn from previous publications and statements on the matter — particularly the 2013 Gospel Topics essay. The new publication mirrors much of the earlier messaging, offering clarification on the history behind the racial restrictions in the Church, while adding a few details that were previously not mentioned.

The same talking points are reiterated: that racism is wrong and incompatible with the teachings of the Church, and that all humans are equal in God’s eyes. However, this publication goes a few steps further by emphasizing that “our differences bring beautiful variety to our lives.” It includes a section titled “Are Church Members or Leaders Racist?” though it avoids a direct yes or no answer. Instead, it repeats that racism is unacceptable and encourages individuals who say or do anything racially insensitive to pray for forgiveness and strive to be better.

Notably, a new section claims that the Church does not discourage interracial marriage, stating that people in interracial marriages often find happiness and fulfillment in their religious pursuits. However, the idea that it’s not discouraged contradicts a quote in a youth manual available on the Church’s website. Former Church President Spencer W. Kimbal said, “We recommend that people marry those who are of the same racial background generally . . . .”

The new publication also makes a point to denounce white supremacy, stating that those who promote white supremacist or “white culture” ideologies are not in harmony with the teachings of the Church. It attempts to soften some of the racially charged passages in the Book of Mormon, asserting that such scriptures have no bearing on people with dark skin today, and that these verses should never be used to justify discrimination or prejudice.

The publication reiterates that even though Jesus is depicted as white in LDS art, it would be a mistake to argue “that Jesus was ‘white’ according to a modern understanding of race.” In the Book of Mormon, however, we read that “in the city of Nazareth I beheld a virgin [Mary], and she was exceedingly fair and white.” (1 Nephi 11:13). Moreover, according to LDS theology, Jesus’ father was not Middle Eastern but God the Father, who in various LDS accounts is described as white skinned and even blue eyed.

As someone who has watched the Church grapple with its racial history for several decades now, this latest publication feels like more of the same: delicately worded, carefully constructed statements designed to shift blame and soften the rhetoric of the past. With no disrespect to the organization or its members, I think the most accurate term to describe this approach is gaslighting. Some Mormons I know personally have felt these PR attempts are almost offensive; they assume readers are either stupid or oblivious to the facts.

Though the racial restriction has been lifted, that alone isn’t enough for many non-white members and progressives. I don’t believe the Church will fully apologize for its past or retract the scriptures that supported it. We’ve seen a similar pattern with polygamy: While the Church discontinued it in the 1890s, it never admitted it was wrong or removed the scriptural justifications. More than a century later, those teachings still cause distress, especially for women, and remain part of Church doctrine. Without apologizing or censuring scripture, the tension around race will remain, just as it has with polygamy.

A few years ago, I visited the Utah town of St. George — founded and still dominated by Mormons. I visited the Deseret Book Store, part of a chain owned by the Church, which sells official literature. I found children’s books about Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, along with books by black Mormons about their struggles for “racial justice.” But in the theology section, I found the traditional racial teachings and doctrines.

I recently asked a mid- to high-level church official about this. He said the traditional views were actually unchanged — the racial passages were literal, and the past racial practices were divinely sanctioned. The difference, he said, is that the Church is trying to reduce criticism while also trying to make its non-white members feel welcome. Race is real, he said, but it will not hinder a person’s hope for salvation or God’s love for him.

This is probably a good summary. Race is just a component of Mormonism, so the church will fall short of the hopes of race realists or white advocates. The church believes its role is to carry out the Great Commission of Jesus: “Take the gospel to all nations.” It will probably not take firm action against white consciousness, but it will also not endorse it.

By American Renaissance | Created at 2025-03-26 19:04:27 | Updated at 2025-04-04 18:58:25

1 week ago

By American Renaissance | Created at 2025-03-26 19:04:27 | Updated at 2025-04-04 18:58:25

1 week ago