Updated

Oct 28, 2024, 08:18 PM

Published

Oct 28, 2024, 06:30 PM

INJE COUNTY, South Korea - In the small mountain village of Sinwol-ri, home to fewer than 100 people, hopes are high that its five new bovine residents will help rejuvenate the village.

The “Flower Cows”, as they are affectionately called, were discovered at an unlicensed farm in Incheon in 2021, and they were facing certain death unless they could be re-homed.

Through the efforts of animal activist group Animal Liberative Wave (ALW), the elders in the Sinwol-ri village – located two hours away by car from Seoul – agreed to take them in.

While the village relies on agricultural produce and cattle livestock for its economy, the arrival of the Flower Cows has inspired it to pivot to becoming South Korea’s first “vegan village”, in a bid to attract younger residents and domestic tourists to reverse the extinction risk brought by rural depopulation.

The vegan-village idea to rejuvenate the place was mooted by ALW activists, and, despite initial misgivings, mayor Jeon Do-hwa, 75, managed to convince “95 per cent” of the residents to support the project.

He said that the villagers were hesitant about the vegan move as some of them are in the livestock business and had no intention of giving it up. They were also not familiar with the concept of veganism.

Mr Jeon assured them that the intention was for a peaceful coexistence between the farms and the village plan to become a vegan sanctuary of sorts.

He also stated that he was not asking all the villagers to switch to a strict plant-based diet, but for them to start embracing and promoting a vegan diet among residents and visitors.

“It may seem like an impossible idea for a livestock village to have vegan practices, but we accepted it because we believe in integration and coexisting harmony. I’m proud to say that we are ahead of other villages in our line of thinking.”

ALW founder Lee Ji-yeon is aware that the vegan-village label could be intimidating to some of the villagers.

“Perhaps we can describe it as a village of ‘life and nature’, where people are trying to move towards a more sustainable lifestyle, side by side with livestock farming that remains the livelihood of many residents here. We are just envisioning a haven of sorts for those who want to live without animal products,” she said.

At the village’s experience centre, visitors get to learn what veganism and animal welfare are about, and to try a healthy bibimbap meal – a rice dish topped with vegetables using fresh produce harvested from the village fields.

The village also hopes to develop vegan recipes using local ingredients.

Other activities include meeting and feeding the Flower Cows, ginseng harvesting and making Korean rice cakes the traditional way.

The project, which started in 2022, received initial support of 2.6 billion won (S$2.47 million), and has had a fresh injection of 600 million won in 2024 under a government initiative to fund the sustainable growth of rural regions by drawing on each area’s unique characteristics for its “local branding”.

In 2023, when the village began its vegan promotion activities, it received 1,300 visitors – a 20 per cent jump from the previous year.

The goal is to hit 2,000 annual visitors by 2025, with the village’s inaugural vegan festival helping to draw the numbers. And by 2030, it aims to attract 50 more families to settle in the village, thereby doubling its current population of 97.

In tandem with having the world’s lowest fertility rate of 0.72 in 2023, South Korean has many rural parts that are in danger of extinction as the young choose to leave for the capital Seoul.

About half of the country’s 52 million population resides in the Seoul metropolitan area which encompasses Incheon city, Seoul city, and Gyeonggi Province that surrounds the capital.

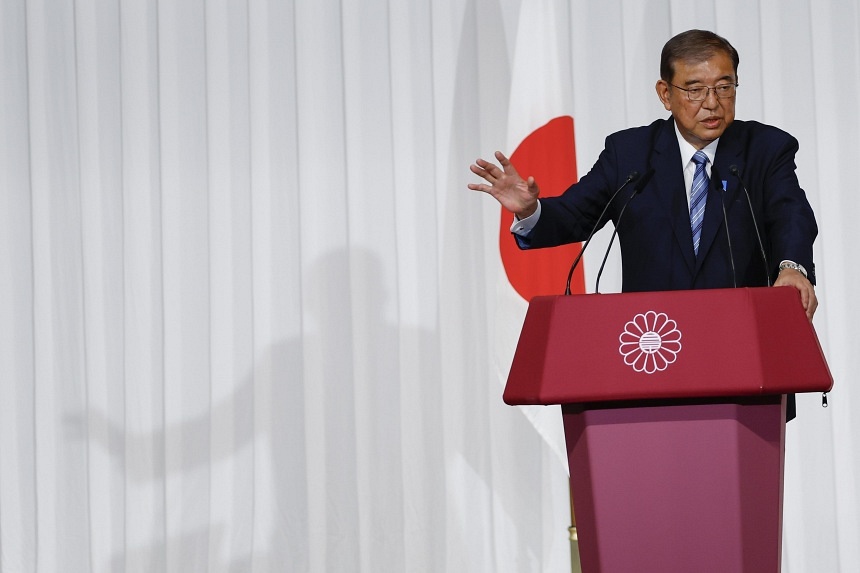

In June 2024, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared the country’s demographic trend a “national emergency” and announced the establishment of a new Population Ministry to tackle its population issues.

Inje county’s Sinwol-ri village comes under Gangwon Province to the east of Seoul. The province has the highest urban migration by young university graduates in the country at 63.6 per cent.

Inje county itself has seen a steady population decline since 1980, from once having 48,000 residents to the current 32,000 residents.

Ms Lee said that after news of Sinwol-ri village becoming a sanctuary to the Flower Cows spread, ALW has received requests to house other animals like dogs and land turtles, rescued from illegal breeding houses, but she has had to reject these requests for now.

“For now, our focus is to properly rehome the cows. In future, when we are more stable and have more land, we can consider these requests.”

In an interview with KBS news, the Gangwon provincial office’s director of the social economy division Kim Sang-beom lauded Sinwol-ri village’s efforts, saying that “Inje county will be the first in the country to offer a vegan culture experience”.

With the funds, a disused primary school that closed down in 2019 is now being converted into accommodation for visitors, with a playground and cultural space for young families and youth to learn about veganism.

A more permanent shelter is also being built for the five Holstein cows, which are currently housed temporarily on a livestock farm.

With more than half of the residents aged over 65, mayor Mr Jeon said it is necessary for the village to attract younger people.

“Our residents do livestock farming for their livelihood, but embracing veganism will bring life back to our village. We need to move with the times, so that we can progress together as a village.”

Five of the ALW activists, including founder Ms Lee, who are mostly in their 30 and 40s, have moved to the village to care for the Flower Cows and are now among the village’s youngest residents.

Mr Chu Hyeon-uk, 41, moved to the village two years ago with his wife and daughter Gaia, seven, and son Sol, five.

He was a make-up artist in Seoul before moving to Canada more than 10 years ago.

After meeting his fellow Korean wife in Canada, they both decided to embrace veganism and became activists.

“Moving to the countryside has always been my dream,” said Mr Chu, who had been an urbanite all his life.

“As the climate crisis worsens, my wife and I believe that we should live a life where we can grow our own food and attain self-sufficiency from what we can cultivate from the land.”

Mr Lee Yong-jae, the village auditor who is also a cattle farm owner, said that despite his initial apprehension at the project, he now believes in the peaceful co-existence of the polar opposites of veganism and livestock farming.

“The villagers are feeling encouraged by the results of the project. Some of them have even tried plant-based meat alternative products for the first time and are not averse to the taste,” he said.

“We should all continue to work together for the benefit of our village.”

By The Straits Times | Created at 2024-10-29 22:23:00 | Updated at 2024-10-30 07:30:38

1 day ago

By The Straits Times | Created at 2024-10-29 22:23:00 | Updated at 2024-10-30 07:30:38

1 day ago