In the title work of Voices of the Fallen Heroes, a newly selected and translated collection of short stories by Yukio Mishima, we encounter a young, blind priest who, in a shamanic rite, is used to channel “the fury and the lamentation” of the Shinto gods. The message they transmit is as cautionary as it is wrathful. “Those who no longer wish to fight now love whatever is base”, they intone through the youth.

Strength is belittled, and the flesh despised.

The young are being strangled

Yet move together towards indolence and drugs and “struggle”

Along paths of hopeless small ideals,

Like sheep.

So recognizable is their description of a spiritually dead world in which “human worth grows less than dross” and in which “a twice withered beauty dominates” that one listener ventures to suggest these must be “spirits of the recent dead, since they [sing] so accurately of the conditions in our time”.

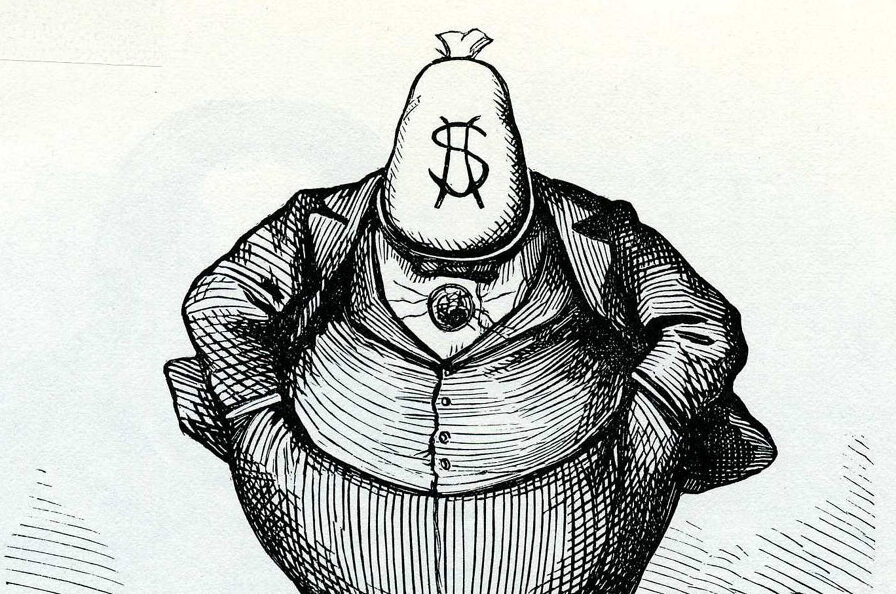

As with the thirteen other stories included in this volume marking the centenary of Mishima’s birth, “Voices of the Fallen Heroes” dates from the 1960s, the final, turbulent decade of the author’s career, just before the final curtain fell with his ritual suicide in 1970. Looking at them together, we can see them as the products of an age in which the Earth seemed to stand perennially on the brink of nuclear catastrophe, and in which postwar Japan, having been remade in capitalism’s faceless image, found itself increasingly contending with mass protest and political extremism. For Mishima’s characters, it seems only natural that this evocation of a world tainted by corruption, materialism and western “morality” should be their own. And so, it takes a moment or two before they realize that these angry spirits belong not to the present but to the past.

Two choruses of men possess the young priest in turn. The first comprises the young officers from the Imperial Army who were executed after a failed coup in 1936, which came about with the aim of restoring direct rule to the emperor. The second is made up of the betrayed spirits of the kamikaze, the “Divine Wind” fighters of the Second World War, glimpsed hauntingly during the séance “with their pilots’ uniforms and bloodstained white mufflers”. As each group mourns Japan’s decline, they also rebuke Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his divinity – prior to 1946, the emperor was revered as a living god. “Why did our divine sovereign lord become no more than human?” they ask from the hereafter.

For Mishima, this question was paramount. What, after all, was the sense of decades’ worth of sacrifice in bloody campaigns waged under divine authority if that divinity was now declared by the emperor himself to have been “false”? How was the warrior spirit to react to such betrayal when Hirohito, having sent out so many men to die for him, then declared their actions to have run counter to his own conscience as a man?

With its themes of Shintoism and ultra-right nationalism, it would be tempting to view this miniature masterpiece of Mishima’s late work solely in terms of its critique of modern Japan and the author’s ideological longing for a return to the samurai principles of bushido. Yet to do so would also be to miss the exquisite layering of the story, its control of language (rendered here with great subtlety in Paul McCarthy’s translation), the complex weaving of myth and history, and the skilful forging of torment and rage into a narrative that has all the poise and austerity of a noh drama.

The tale also gains considerably by being read within the broader contexts offered by this eclectic collection, wherein its themes find resonances in unexpected places. Although he cut his own life short at the age of forty-five, Mishima was prolific. In addition to his more than thirty novels, forty plays and dozens of essay collections, he wrote almost 200 short stories, which alone take up twenty-five of the forty volumes of his collected works in Japan. As might be expected, the fourteen tales selected here by Stephen Dodd are every bit as diverse as they are idiosyncratic, opening a narrow but often alarming window on to the creative life of the artist in his maturity.

Several of the earlier works included in the first half of Voice of the Fallen Heroes engage in what John Nathan – the author of the volume’s illuminating introduction, and also one of the book’s nine translators – terms a kind of “memorialisation” of episodes from the frenetic international life that Mishima led in that final decade. In “The Flower Hat”, for example, which is based on an episode from his travels in the United States in the early 1960s, a sun-drenched urban park scene acquires “a mantle of death” as the narrator is visited by a dazzling vision of nuclear apocalypse. “Cars”, by contrast, which was composed after Mishima passed his own driving exam, takes the humdrum, unlikely site of a test centre and spins from it a hyperreal and unnerving account of the manipulation enabled by consumerism. While their themes remain typical of Mishima, the moods of both stories are intimate and subdued, their drama turned inwards; they show the author in a more reflective, more contemporary key than we have perhaps come to expect from him.

It is in the second half of the collection that we find some of the more characteristic – thematically, at least – and more arresting of Mishima’s late works. “The Strange Tale of Shimmering Moon Villa” begins with the friendship between a young country boy and the feeble son of a marquis and ends in shocking violence and murder. With classical allusions and undertones of eroticism and perversion, the story clearly takes its cues from Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s decadent work of the 1920s, but in Mishima’s hands all the opulence and lavishness is pared back to leave a chilling study in perspective and “muted horror”. Allusions to the noh theatre likewise abound in “The Dragon Flute”, in which, following a day of training and manoeuvres, a beautiful young army recruit performs an ancient melody on the Japanese transverse flute for his comrades, mesmerizingly combining Mishima’s love of militarism with all manner of classical references and a homoeroticism that is veiled with, if anything, only the thinnest gossamer.

Yet of all the stories included here, perhaps none is more unexpected – and at the same time more quintessential – than “The Peacocks”. In this surreal tale, we are introduced to a man who learns of “the world’s most extravagant crime”: the killing of twenty-seven peacocks in a nearby amusement park. Despite his obsessive love of these creatures – “birds for whom the glitter of day and of night were the same” – his most bitter source of regret is at not having witnessed the moment of the crime itself. His reason? Because their deaths were “not a rupture but the sensual intertwining of beauty and destruction”. Here, in brutal, brilliant prose, we see a vivid manifestation of Mishima’s obsession with slaughter as a form of art, one that distils his hallmark preoccupations of death and beauty into a singularly intense poetic expression.

In his introduction, Nathan remarks on the challenge faced by the reader in “dragging [Mishima’s] work from the shadow of his final act”. That this act attempted to make of Mishima’s life an art makes this challenge, in some sense, moot. Either way, what this fine collection consistently demonstrates is how fundamentally, disturbingly, enduringly relevant Mishima’s writing remains. It is about a concern for the world around us so profound as to be transformative, transgressive even. It is, moreover, concerned with love – be it passionate or perverse, melancholy or obsessive, destructive or betrayed, forever driven to its extremities and beyond. It is at times agonizing and yet, as one of Mishima’s narrators observes, also “lyricism at its maximum, like a bowstring pulled so hard it bites the finger’s skin”.

Bryan Karetnyk is a British writer and translator. He teaches Russian at the University of Cambridge

The post Terrible beauty appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:02 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:25:22

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:02 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:25:22

1 week ago