At the end of June earlier this year, a diesel freight train wound its way from the port of Immingham, just north of Grimsby, to the Ratcliffe-on-Soar coal power station near Nottingham, 80 miles inland. It was the last delivery of coal freight in the UK to the last remaining coal-fired power station, which ceased operations on September 30.

Twenty years ago coal helped generate more than a third of the UK’s electricity. I remember, as a child, being driven past cooling towers spewing out steam by the side of the motorway. Today, the GridCarbon app shows me the source of our electricity at any given moment. On blustery days, wind often accounts for more than 20 per cent of total output, and solar can reach similar levels if the conditions are right. Meanwhile, gas-derived electricity hit an all-time low this August.

It is a remarkable change, but one that can induce a false sense of achievement in our efforts to move beyond fossil fuels. Marketing executives, oil companies, politicians and historians like to talk about the “energy transition”. According to them, our reliance on raw materials for power generation has moved historically from wood, to coal, to oil and now to renewable sources. Consultants have nice neat graphs that lead up to 2050, when most countries will have supposedly reached “net zero” carbon emissions. But in their most recent books historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz and journalist Ed Conway both argue that the language of “progress” belies the complexity of what’s really happening and what needs to happen next.

To begin with, if we have left coal behind, why are we still burning so much of it? The world is set to burn more coal this year than ever before in history. We think of it as a Victorian or post-war fuel – but the reality is that it underwrites our whole era of AI and smartphones, says Fressoz. China has more than 1 billion internet users, and they charge their devices using coal-fired electricity.

Coal is critical to how we make things. China produces more than 1 billion tonnes of steel a year, all done using coal, and there crude steel demand has increased by 50 per cent since 2010, according to the mining company BHP. And, as Conway puts it, “China produces more steel every two years than the UK’s entire steel output since the industrial revolution.” The result is that 80 per cent of the world’s primary energy supply still comes from fossil fuels, a share that hasn’t changed much over the years. How can we kid ourselves we’re in a “transition?”

We’re also consuming more wood than we did in the nineteenth century, not just as cardboard packaging but in the form of charcoal, still widely used for heating and cooking in the developing world. Any visitor to the Democratic Republic of Congo can see the piles of charcoal collected and gathered by the side of the road and taken away on bicycles. According to Fressoz, the DRC’s capital, Kinshasa, consumes 2.15 million tonnes of charcoal every year (for comparison, Paris got through 100,000 tonnes in the 1860s). That’s 17 million tonnes of wood a year. “There has never been an energy transition out of wood”, Fressoz declares.

Another glance at the GridCarbon app shows that one undeviating source of UK electricity comes from “biomass”. This means the Drax power station in Yorkshire, which burns wood pellets, from North America and elsewhere, to generate electricity. It accounts for three per cent of the UK’s carbon emissions as a result. Europe, Fressoz tells us, every year burns just under 200 million cubic metres of wood for domestic purposes and to generate electricity – almost twice as much as a century ago.

In More and More and More, Fressoz demolishes other historians’ use of the energy transition framework. They have, he says, treated historical transitions in ways that downplay the scale of the challenge now facing us, he argues, and which allow oil companies (still) to drag their feet. In the 1960s, renewables advocates never expected clean energy to compete with fossil fuels. But by the end of the 70s, with a growing awareness of how different energy sources could be employed to meet rising demand, “the idea of the energy transition was becoming commonplace, a discursive umbrella encompassing all possible futures”, he writes.

Jimmy Carter summed up the new understanding in 1977: “Twice in the last several hundred years, there has been a transition in the way people use energy. The first was about two hundred years ago, when we switched from wood … to coal … This change became the basis of the Industrial Revolution. The second change took place in this century, with the growing use of oil and natural gas”. The New York Times added: “The United States and the world are at the beginning of a new energy transition”.

But to Fressoz energies and materials are “in symbiosis as much as in competition” and “we cannot simply use a technological substitution model to understand their dynamics”. We have never moved simply from one source of energy, or raw material, to another. Rather, increases in the demand for one commodity have supported demand for others. Far from diminishing the need for wood, the rise of coal in the nineteenth century actually increased it: coal-mining galleries and tunnels needed vast numbers of pit props, and wood consumption across the UK increased by a factor of six between 1830 and 1930.

In Material World, Conway highlights how global economic growth has led not to substitution but to increased demand for all raw materials and fossil fuels. We are digging up more stuff than ever before, not counting the waste rock removed in the extraction of copper and other metals. He gives us a detailed tour of the minerals without which we couldn’t function – sand, salt, iron, copper, oil and lithium. The book’s tone is an engaging mix of Vaclav Smil, the Czech–Canadian environmental scientist, and the economics journalist Tim Harford, with many excellent descriptions of site visits to copper mines in Chile and salt mines in the UK.

Like Smil, Conway enjoys pouring cold water on our hopes of quickly moving beyond fossil fuels. The synthetic graphite in your electric car battery comes from petroleum coke, one of the largest suppliers of which is an oil refinery in the Humber Estuary. The coke is shipped to China, where it is burnt with coal. The graphite derivative is then incorporated into batteries in “gigafactories” which consume huge amounts of energy from a coal-heavy grid. Wind turbines also use of a lot of Chinese steel, all of which is made using fossil fuels. And the supply chain for the high-purity polysilicon used in solar panels is equally shocking. Quartz rock is mixed with coking coal and heated in a furnace to more than 1,800 degrees Celsius. It’s “like the Middle Ages”, one analyst tells Conway. “There are guys heaping coal [into the flames]. It’s like the mines of Moria from Lord of the Rings”. China produces most of this substance, often in coal-heavy provinces.

And it’s not just heavy industry that’s to blame: fossil fuels have seeped into every crack in our productive economy. Conway seizes on the humble tomato to show how so “[m]uch of what we eat today is, one way or another, a fossil fuel product”. In the tomato’s case, natural gas is burnt to power the boilers that heat the greenhouses where tomatoes are grown. Carbon dioxide from the boiler’s gas is also piped into the greenhouse to accelerate this process. The same is true for cucumbers, peppers and lettuces. Fertilisers made by natural gas are also used “for the vast majority of the world’s crops”, according to Conway.

Three unfortunate trends have coincided with efforts, in the West, to combat climate change. One is the loss of an understanding of the material foundations of our economic growth (both books bring this out). We are not doing the growing ourselves. Offshoring to China has led to the shutdown of key industries in Western countries, while higher energy prices have affected those that remain.

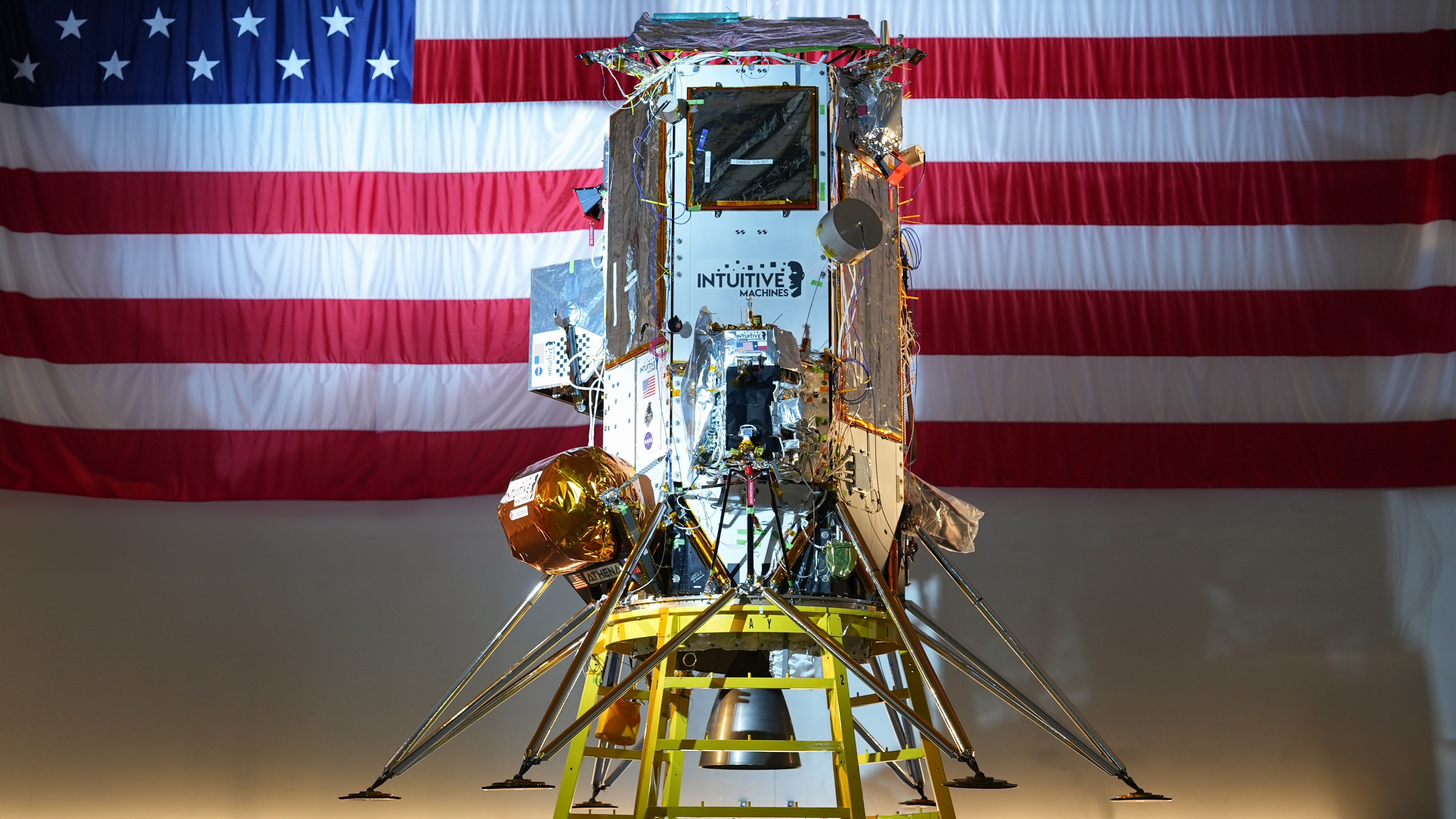

Another is the rise of corporate sustainability, “ESG”-speak and the seductive marketing opportunities of an “energy transition” that has glossed over the complexity of how things are made, and the trade-offs involved. How will we make the steel, silicon, graphite and lithium needed for the new-generation renewable technologies? The impact of these processes is at odds with the images – so embedded now in our thinking – of a clean energy transition, made up of wind turbines and solar panels planted on beautiful, empty landscapes.

And lastly there is the belief (less prevalent since Covid) that innovation and capitalism will magically solve our problems. Whereas in fact it is China and its state-directed industrial policies that have lowered the cost of solar panels and batteries, making clean energy affordable for the first time.

Both books provide a corrective to the lazy thinking that surrounds our current predicament. But they don’t offer much in the way of solutions. Conway is very good at describing the material world as it is, and sketches out a vision of the future towards the end of his book. But I was curious as to how we get from where we are to the promised land he describes – one in which we recycle materials, use hydrogen to make green steel, and have abundant clean energy. Green steel is expensive, in which case the question becomes: how do we make it cheap and competitive, and is such an end in sight? Steel accounts for around 7 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, so we need to find the answer.

Likewise, reading Fressoz I was left wondering what the broader lesson of More and More and More might be. He makes the point that the problem with thinking too much about past energy transitions is that it undermines the challenge of the present. I wanted this idea put more practically. How do we frame the challenges of the present in a way that induces action, and not apathy and despair? Fressoz is right, anyway, when he says that a “‘transition’ to renewables that would see fossil fuel [use] diminish in relative terms but stagnate in terms of tonnes [produced] would solve nothing”.

China produces over half the world’s steel and two thirds of its lithium, and refines most of the copper. What happens to Chinese industry is therefore an existential question for the planet. According to one analysis, the country is responsible for 30 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and 90 per cent of the growth in CO2 emissions since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015. It is also building and installing solar panels, wind turbines and batteries at an unprecedented rate.

The West has a role in this process, of course, and two recent shocks to our system have helped us realise the degree of complexity involved in global manufacture – as both these books argue. First, Covid-19 exposed the fragility of our supply chains, and our inability to produce even basic medical goods. In the United States and Europe, that realisation has hastened efforts to localize manufacturing and reindustrialize economies. The Biden administration has handed out billions of dollars in grants, loans and tax credits to support new factories and plants. Second, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has laid bare the strategic fallacy of relying on Russian gas, and accelerated a shift away from fossil fuels.

It will be a difficult journey. We urgently need to combine the benefits of our global free market – where cost is everything – with incentives for innovations and efforts that clean up the “material world”. At the same time, we need to ensure that cheap materials made using fossil fuels cannot be dumped on markets, undermining efforts to clean up. One way to do that is via a carbon border tax that puts a price on the amount of embodied carbon in an imported product. Global carbon markets, provided they are stringent enough, could help level the playing field, or at least hasten the decarbonization of Chinese manufacturing. As John Podesta, Joe Biden’s senior adviser on international climate policy puts it: “The global trading system doesn’t properly take account of embodied carbon in tradable goods”. We cannot slip back into complacency again – the “ethereal world,” Ed Conway calls it – transfixed by our smartphones and computers while someone else provides the steel, the copper, the lithium, the silicon and the solar panels outside the window.

Henry Sanderson is a journalist and the author of Volt Rush, the Winners and Losers in the Race to Go Green, 2022

The post The long reign of King Coal appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:35:53

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:04 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:35:53

1 week ago