For Malaysian recruiter Joseph Cheng, Donald Trump’s first stint in the White House brought a windfall. The US president’s trade war with China triggered a rush of Chinese companies relocating to countries like Malaysia, desperately seeking refuge from punitive tariffs.

“They sent their goods here to be repackaged … and then sent them onto the US,” said Cheng, director of recruitment agency Agensi Pekerjaan TSM, recalling the frantic scramble to find staff to accommodate the influx.

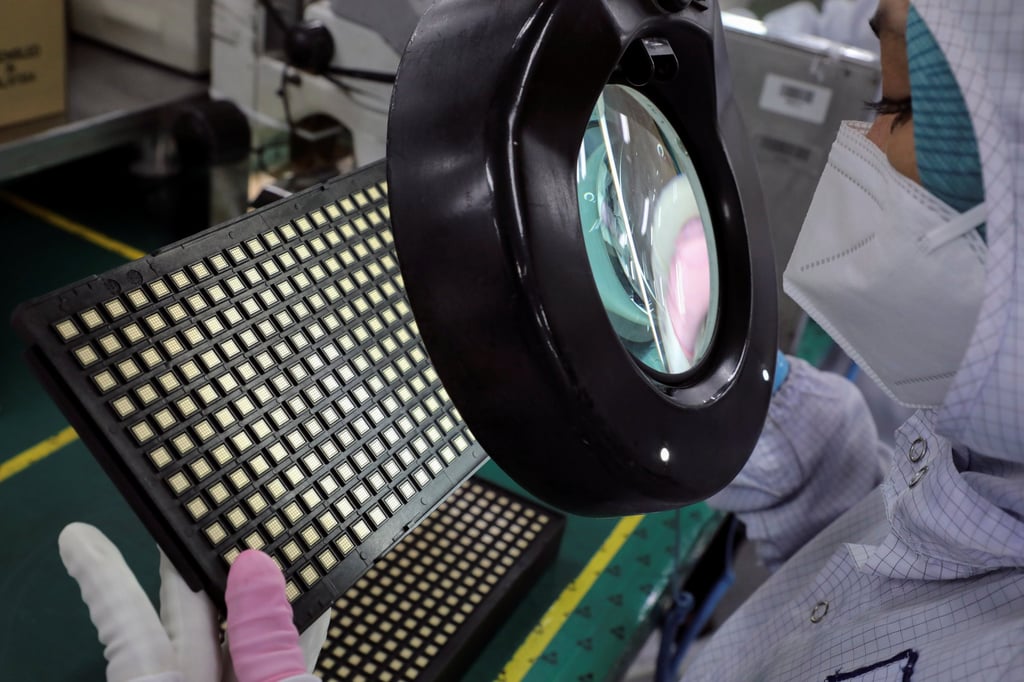

This manufacturing exodus didn’t just benefit Malaysia; it brought a surge of investment and jobs to Thailand, Vietnam and India too as Chinese firms sought to obscure their supply chains.

Now, as Trump gears up for a second act, Cheng’s optimism has turned to apprehension. He fears the next wave of tariffs could be “more crazy”, with Southeast Asian economies unlikely to reap many benefits from American protectionism this time around.

The China hawks poised to fill Trump’s new administration are acutely aware of so-called third-country workarounds, raising the spectre of tariffs as high as 20 per cent on imports from nations with significant trade surpluses with the US, particularly in strategic sectors such as semiconductors and electric vehicles.

For countries like Malaysia, the implications could be dire: foreign investors might retreat, exports could plummet, and new industries could stall.

By South China Morning Post | Created at 2024-11-23 00:01:13 | Updated at 2024-11-23 04:10:22

4 hours ago

By South China Morning Post | Created at 2024-11-23 00:01:13 | Updated at 2024-11-23 04:10:22

4 hours ago