Research conducted by the UN human rights office, OHCHR, revealed that 67 nuclear tests performed between 1946 and 1958 by the United States Government in the Marshall Islands left communities displaced and contributed to radioactive land and sea pollution.

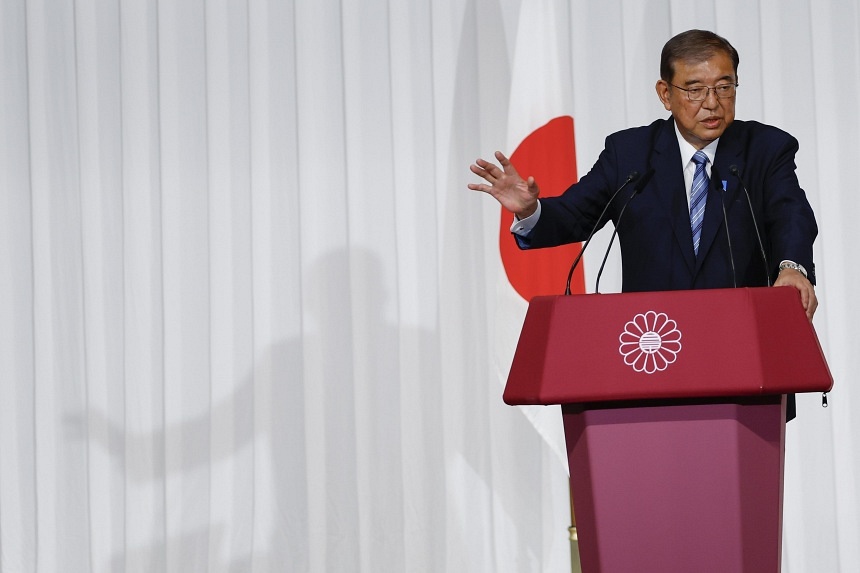

“The nuclear legacy casts a long shadow across generations and the High Commissioner’s report highlights this legacy remains a lived reality for the Marshallese people,” Nada Al-Nashif, the UN Deputy High Commissioner, said in an opening statement at an Enhanced Interactive Dialogue on the matter in Geneva.

Cancer, miscarriages and 'jellyfish babies'

Through workshops and consultations, OHCHR found that radiation exposure from the nuclear tests caused the “proliferation of cancers, of painful memories of miscarriages, stillbirths, and of what some Marshallese refer to as ‘jellyfish babies’ – infants born with translucent skin and no bones.”

OHCHR witnessed the widespread displacement of Marshallese Indigenous People which contributed to their disconnect from their cultural traditions, including burial practices.

“But the human rights impacts of the nuclear legacy are not limited to what is known and easily quantifiable,” Ms. Al-Nashif said. “They are also rooted in pain that cannot be measured and facts that remain unknown.”

The deputy rights chief said information gaps related to the testing “were the single most prevalent issue raised in OHCHR’s consultations with the Marshallese.”

She noted that the human rights office is ready to assist the National Nuclear Commission (NNC) of the Marshall Islands with “long-standing consequences” of those impacted including “displacement, health crises, and the erosion of livelihoods.”

OHCHR's recommendations

To address the nuclear legacy, the report recommends that the Marshall Islands, the US Government, the UN and other actors consider establishing truth and non-repetition mechanisms, as well as adopting and supporting a transitional justice-driven approach.

“The lessons of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands are lessons for the whole world, as there are other areas, communities and countries that were and continue to be affected by nuclear testing,” Ms. Al-Nashif said.

“When it comes to human rights and environmental crises, we must stand together to prevent them, and to promote accountability, truth and reparations for them; protecting and empowering those most at-risk from their impacts,” she continued.

Testimonies of pain

Ariana Tibon-Kilma, the chairperson of the Marshall Islands NNC, presented personal testimonies to the human rights council of the intense pain and suffering her community faced during and following the nuclear tests.

She described how the nuclear testing happened against the wishes of the Marshallese and how only hours after a detonation, people scratched off their own skin and mothers watched as their children’s “hair fell to the ground and blisters devoured their bodies overnight.”

She explained how those relocated from the islands were then subjected to a medical testing programme lasting more than 40 years which included the removal of healthy teeth, bone marrow and other body parts, “to be stored in a laboratory for research purposes.”

To remedy this and many other damaging consequences of nuclear testing on the Marshall Islands, the UN deputy rights chief insisted that “uncovering the truth” and filling gaps in the factual record of the US programme were key to justice, accountability, reparations and reconciliation.

“As I watched my loved one endure relentless pain, I grappled with a profound sense of helplessness, the weight of their suffering entwined with my own,” Ms. Tibon-Kilm said, adding “let us remember that the dignity of every individual, especially those in their most vulnerable moments, must be fiercely protected and upheld.”

She, along with other Marshallese and UN experts included in the dialogue underscored the OHCHR report’s recommendation for the adoption of a transitional justice-driven approach, to address the nuclear legacy.

By UN (Asia) | Created at 2024-10-29 19:21:04 | Updated at 2024-10-30 07:33:01

3 weeks ago

By UN (Asia) | Created at 2024-10-29 19:21:04 | Updated at 2024-10-30 07:33:01

3 weeks ago