U.S. Air Force officials remain focused on the ability to disperse forces to far-flung operating locations as the primary means of reducing vulnerability to enemy attacks. They also continue to downplay any talk of doing more to physically harden existing bases. This is despite acknowledgments that large established facilities are still expected to play key roles in any future conflict and can no longer be considered sanctuaries. All of this comes amid an increasingly heated debate about whether the entire U.S. military should be investing in new hardened aircraft shelters and other similar infrastructure improvements, which TWZ has been following closely.

Air Force Gen. Kevin Schneider, head of Pacific Air Forces (PACAF), the service’s top command in the Indo-Pacific region, spoke yesterday about current “resilient” basing priorities during a panel discussion at the Air & Space Forces Association’s (AFA) 2025 Warfare Symposium, at which TWZ was in attendance. The panel’s main topic was Agile Combat Employment (ACE), a term that currently refers to a set of concepts for distributed and disaggregated operations centered heavily on short notice and otherwise irregular deployments, often to remote, austere, or otherwise non-traditional locales. The other branches of the U.S. military, especially the U.S. Marine Corps, have been developing similar new concepts of operations.

“So the Air Force wants to populate the Indo-Pacific with dispersed operating locations to support ACE. However, the Air Force also needs to invest heavily in resilient infrastructure at its main operating bases,” Heather “Lucky” Penney, the panel’s moderator, said as a lead in to a question. “So, General Schneider, could you speak to what the Air Force is doing to balance the demand for resilient infrastructure while also building out ACE operating locations across the Indo-Pacific?”

Penney is currently a senior fellow at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies and also an Air Force veteran who flew F-16s.

“It’s different in the Indo-Pacific than it is in Europe. [We] do not have NATO. You have a couple of – five bilateral treaty partners. Two of them are Korea and Japan where we share basing,” Schneider said in response. “We also have the joint force demands on our bases. And their are benefits to that, as well. I like having the Army on our bases, especially when they have Patriots [surface-to-air missile systems] and other capability that helps us defend.”

Elements of a US Army Patriot surface-to-air missile battery at Osan Air Base in South Korea, which the Air Force also operates from. US Army

Elements of a US Army Patriot surface-to-air missile battery at Osan Air Base in South Korea, which the Air Force also operates from. US Army It’s worth noting here that currently the U.S. Army is the lead service for providing air and missile defense for Air Force bases at home and abroad. There has been talk recently about the Air Force potentially taking a greater role in this regard. The Army has been facing its own struggles in meeting growing demand for ground-based air and missile defenses.

“So, we will have the need for bases, the main operating bases from which we operate,” the PACAF commander continued. “The challenge becomes, at some point, we will need to move to austere locations. We will need to disaggregate the force. We will need to operate out of other locations, again, one for survivability, and two, again, to provide response options.”

Ensuring the continued viability of main operating bases and work related to ACE both “cost money,” he said. The Air Force is then faced with the need to “make internal trades” funding-wise, such as “do we put that dollar towards, you know, fixing the infrastructure at Kadena [Air Base in Japan] or do we put that dollar towards restoring an airfield at Tinian,” according to Schneider.

What Gen. Schneider was referring to at the end here is the massive amount of work that has been done to reclaim North Field on the island of Tinian, a U.S. territory in the Western Pacific, since the end of 2023. North Field was originally built as a huge B-29 bomber base during World War II. It was the biggest active airbase anywhere in the world before being largely abandoned after the war ended. There has also been additional expansion of the available facilities at Tinian International Airport in recent years, ostensibly to improve its ability to serve as a divert location for U.S. military aircraft in the event that the critically strategic Andersen Air Force Base on nearby Guam is rendered unusable for any reason.

Side-by-side satellite images showing Tinian’s North Field in December 2023, at left, and January 2025, at right, underscoring the massive amount of work that has been done to reclaim the base. PHOTO © 2025 PLANET LABS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION

North Field is a prime example of the Air Force’s current focus on ACE as the centerpiece of how it expects to fight in the future, especially in a high-end fight in the Pacific. The airfield’s grid-like layout inherently presents additional targeting challenges for a potential adversary like China, as you can read about in more detail in TWZ‘s recent story on what has been happening over the past year or so on Tinian.

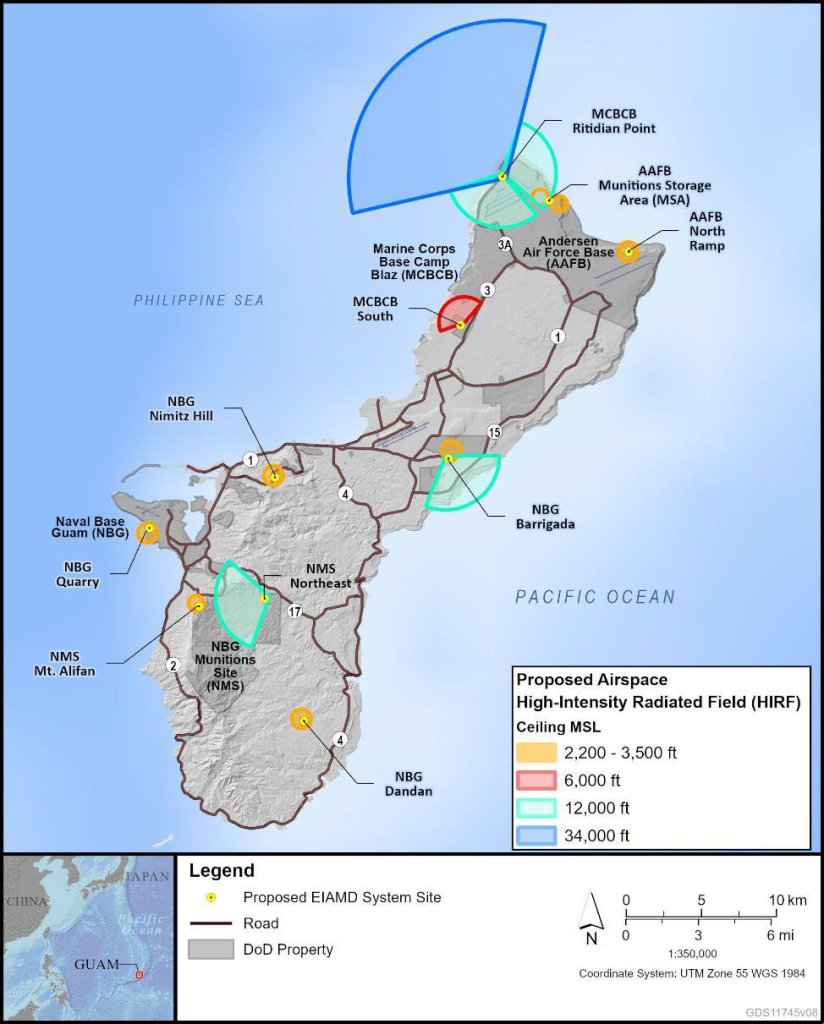

Guam has also seen significant military construction work in recent years, including to refurbish more of the World War II-era Northwest Field on the island to support ACE operations. Guam is now set to get a huge new air and missile defense architecture full of new surface-to-air missile launchers, radars, and other supporting facilities, as you can read more about here.

A new tilting missile launcher installed on Guam as part of work on a new air and missile defense architecture for the island. Missile Defense Agency

A new tilting missile launcher installed on Guam as part of work on a new air and missile defense architecture for the island. Missile Defense Agency  A map showing radar arcs and other details giving a sense of the size and scope of the current plans for the new air and missile defense architecture on Guam. Missile Defense Agency

A map showing radar arcs and other details giving a sense of the size and scope of the current plans for the new air and missile defense architecture on Guam. Missile Defense Agency “These are the things that we need in our main operating bases. These are the things that we need to project power,” Gen. Schneider added, but did not explicitly mention hardened infrastructure. He also emphasized a desire to work more with regional allies and partners to “gain greater access to those fields that are already in operating condition.”

Air Force Gen. James Hecker, another member of yesterday’s ACE panel at the AFA Warfare Symposium, also stressed the continued importance of existing main operating bases. Hecker, who is head of U.S. Air Forces in Europe and Air Forces Africa (USAFE-AFAFRICA), as well as NATO’s Allied Air Command, highlighted significant challenges his service faces in successfully executing large-scale dispersed operations in the future, as well.

“I have the opportunity to talk to the Ukrainian air chief once every two weeks, or so. And they’ve been very successful not getting their aircraft hit on the ground,” Hecker said. “And I ask him, I said, ‘How is that? What do you do?’ And he goes, ‘Well, we never take off and land at the same airfield. I’m like, okay, you know, that’s pretty good. Keeps the Russians on their toes.”

“I got tons of airfields from tons of allies, and we have access to all of them. The problem is, I can only protect a few of them,” he continued. “We can’t have that layered [defensive] effect for thousands of airbases. There’s just no way it’s going to happen.”

Elements of a Patriot surface-to-air missile battery seen at Rzeszów-Jasionka Airport in Poland in 2023. INA FASSBENDER/AFP via Getty Images INA FASSBENDER

Elements of a Patriot surface-to-air missile battery seen at Rzeszów-Jasionka Airport in Poland in 2023. INA FASSBENDER/AFP via Getty Images INA FASSBENDERHowever, Gen. Hecker warned that just dispersing forces to more bases will not be a solution in of itself, either.

“So, to go think you’re going to land at another airfield and hang out there for a week with no defense, you’re going to get schwacked. It’s going to happen,” he said. “You can only stay there for a little bit, and then you’ve got to get back to your main operating bases.”

“It’s going to be much shorter operations. You know, we’re not talking weeks anymore,” Hecker explained. “We’re talking days, and sometimes we’re talking hours, if you want to be survivable. And then back at your main operating base, you’ve got the layered defense.”

Hecker called attention to how shrinking adversary kill chains are a key driving factor here, specifically highlighting Russia’s efforts to reduce the total time it takes to complete a targeting cycle in operations in Ukraine. China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been doing the same, particularly with the help of a growing array of space-based surveillance assets. The time it takes from certain munitions like ballistic and hypersonic missiles to actually get to their targets after launch can also be very short.

“So it’s really evolving the ACE concept,” the Air Force’s top officer in Europe noted.

Realities like the ones Hecker outlined are exactly what has been driving increasing criticism of the Air Force’s current focus on ACE, as well as the service’s general approach to basing and base defense, including from members of Congress and outside experts.

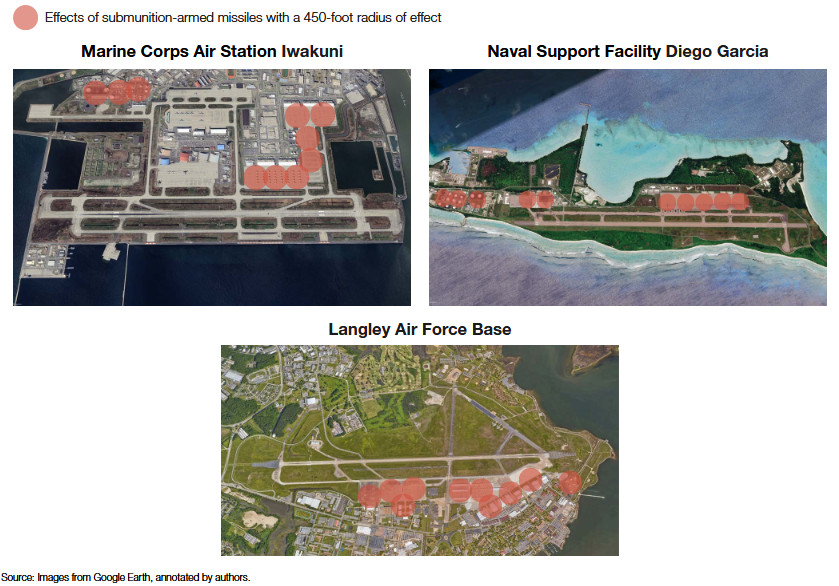

Just in January, the Hudson Institute think tank in Washington, D.C., published a report warning that a lack of hardened and unhardened aircraft shelters, as well as other exposed infrastructure, at bases across the Pacific and elsewhere globally has left the U.S. military worryingly vulnerable. The report’s authors assessed that just 10 missiles with warheads capable of scattering cluster munitions across areas 450 feet in diameter could be sufficient to neutralize all aircraft parked in the open and critical fuel storage facilities at key airbases like Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni in Japan, Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, or Langley Air Force Base in Virginia.

Hudson Institute

Hudson Institute Another report that the Henry L. Stimson Center think tank published last December highlighted how Chinese missile strikes aimed just at cratering runways at bases in the Pacific could upend the U.S. military’s ability to project airpower.

“While ‘active defenses’ such as air and missile defense systems are an important part of base and force protection, their high cost and limited numbers mean the U.S. will not be able to deploy enough of them to fully protect our bases,” a group of 13 Republican members of Congress wrote in an open letter to the Air Force back in May 2024. “In order to complement active defenses and strengthen our bases, we must invest in ‘passive defenses,’ like hardened aircraft shelters… Robust passive defenses can help minimize the damage of missile attacks by increasing our forces’ ability to withstand strikes, recover quickly, and effectively continue operations.”

“While hardened aircraft shelters do not provide complete protection from missile attacks, they do offer significantly more protection against submunitions than expedient shelters (relocatable steel shelters),” the letter’s authors added. More shelters “would also force China to use more force to destroy each aircraft, thereby increasing the resources required to attack our forces and, in turn, the survivability of our valuable air assets.”

Outside of the United States, especially in China, but also in Russia, North Korea, and many other countries, there has been a growing trend in the expansion of hardened and otherwise more robust airbase infrastructure.

A satellite image showing the 16 new aircraft shelters under construction at Tuchengzi Air Base in northeastern China in 2022. Maxar via USAF A satellite image showing the 16 aircraft shelters at Tuchengzi under construction. Maxar via USAF

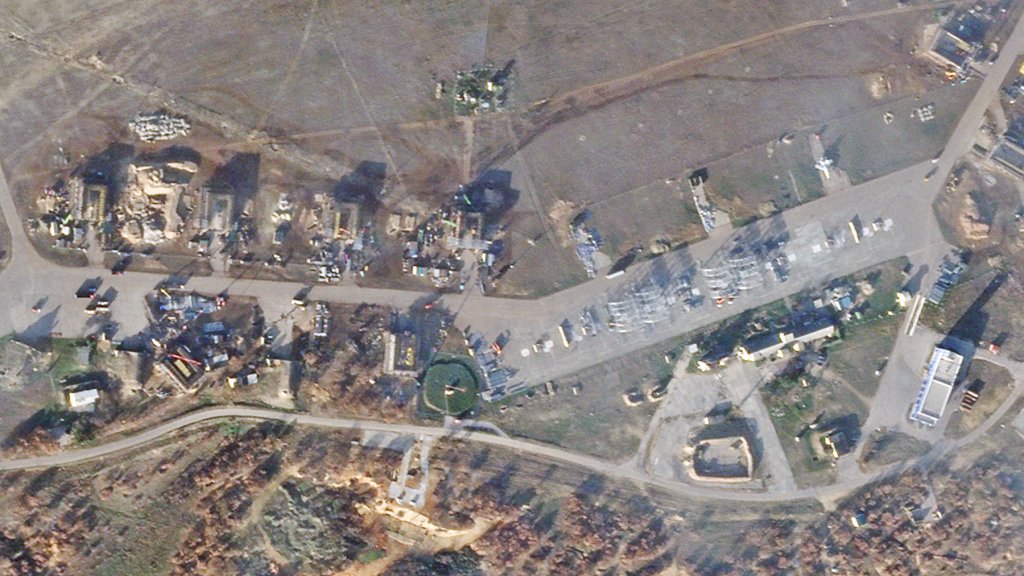

A satellite image showing the 16 new aircraft shelters under construction at Tuchengzi Air Base in northeastern China in 2022. Maxar via USAF A satellite image showing the 16 aircraft shelters at Tuchengzi under construction. Maxar via USAF A Dec. 19, 2024 satellite image of Russia’s Belbek Air Base on the occupied Crimean Peninsula showing work on new HASs and other construction. PHOTO © 2024 PLANET LABS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION

A Dec. 19, 2024 satellite image of Russia’s Belbek Air Base on the occupied Crimean Peninsula showing work on new HASs and other construction. PHOTO © 2024 PLANET LABS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION Air Force officials have also pushed back more actively on the idea of investing in additional physical hardening in recent years.

“I’m not a big fan of hardening infrastructure,” Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach said at a roundtable at the Air and Space Forces Association’s main annual symposium in 2023. “The reason is because of the advent of precision-guided weapons… you saw what we did to the Iraqi Air Force and their hardened aircraft shelters. They’re not so hard when you put a 2,000-pound bomb right through the roof.”

Wilsbach was commander of PACAF at the time and has since become head of Air Combat Command (ACC), which oversees the vast majority of the Air Force’s tactical combat jets and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft.

The comments yesterday from the Air Force’s current top officers in the Indo-Pacific region and Europe highlighting the continued focus on ACE and the challenges with that strategy are only likely to further fuel the ongoing debate about building more hardened infrastructure to help ensure American forces can continue to project air power in future fights.

Contact the author: [email protected]

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-05 19:37:55 | Updated at 2025-03-06 06:09:53

10 hours ago

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-05 19:37:55 | Updated at 2025-03-06 06:09:53

10 hours ago