They’re closing the Central YMCA, just off Tottenham Court Road: the swimming pool, the sports hall, the social and educational spaces, the slightly run-down café, home to 3,600 members and 20 clubs and organizations, including various rehab classes, and stroke support groups, and pottery, and language classes, and all the other good stuff that goes on in these sorts of places. There was no public consultation, of course, no notice. And I know it doesn’t really matter, in the grand scheme of things, but it does: another tiny nail in the coffin. And it’s not just because I used to be a member there.

It was when I was working at the old Foyles on the Charing Cross Road: at lunchtime I used to pop in for a sandwich at Battista’s on the corner, near the Pillars of Hercules, or I’d browse in the second-hand bookshops further down the road, or I’d head up to the YMCA for a swim. But now it’s been sold to a developer, the oldest YMCA in the world. It’ll close its doors on February 7, forever. There’s a campaign to save it: look it up, particularly if you’re a politician or you’re someone with power and influence, or deep pockets, and your heart’s in the right place. Maybe it’s not too late.

And yes, I know that the selling off of yet another vital community asset is a minor footnote in the narrative of contemporary life, really; a total irrelevance. Which is the problem. We’ve come to accept as entirely normal the gradual erosion of public amenities and community services in our cities and towns, the slow but inevitable decline of all those places that were designed to nurture human connection. The scout hut, the playing fields, the church halls, the youth clubs, the community centres: this was England. The closure of the Central YMCA isn’t just about the closure of a building: it’s about the fabric of public life, which has been slowly and methodically torn apart and shredded, bit by bit, tiny piece by tiny piece, over many years.

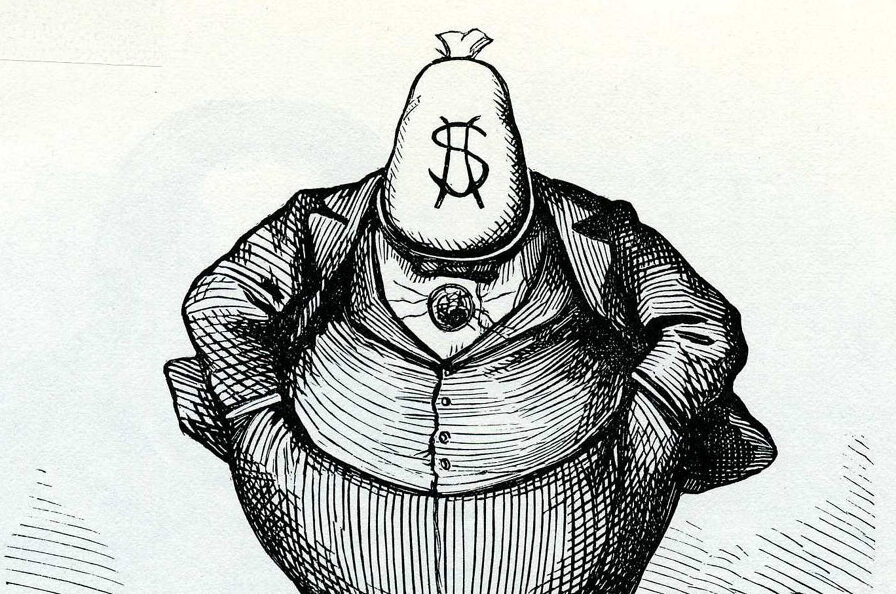

Wherever you live, and whatever your political persuasion, you know it, you’ve seen it, and you know exactly how it goes: the pretend consultations, or the no-consultations-at-all, the claims that it’s all for the better and that times have changed, and so the slow, gradual privatization of public space and the corresponding degradation of our social lives. It’s not a new phenomenon, nor is it limited to London. You’ll have your own examples: the closure of some library, or a school, a pub, the pool, whatever it is, or whatever it was. It’s inevitable – so, who cares?

But just a reminder, why it matters – a footnote to the footnote. Henri Lefebvre, in La Production de l’espace (1974), argues that urban spaces are not just neutral backdrops to social life, but are actively shaped by political, economic and social forces. Lefebvre described how the modern city creates environments that prioritize individualism, consumption and spectacle, while eroding spaces that foster collective engagement and solidarity. Well he would say that, of course: he was a Marxist. But you don’t have to be a Marxist to understand that the YMCA is not the same thing as a Pure Gym: the YMCA is a space for both physical and social wellbeing. At one end of the pool you get your OAP aqua-aerobics and at the other end, the schoolkids learning to swim. Tums and Bums, basketball, Zumba. There was even a prayer room: you don’t get that at a David Lloyd.

I could go on and I could go back, belabouring the point, all the way to Aristotle, who believed that there was a fundamental connection between public life and civic virtue. You could pretty much pick anyone who’s ever written anything on the subject of social space to realise that the closure of a place like the YMCA is a bad idea. Richard Sennett, in The Fall of Public Man (1977), who wrote about how modern urban life has become increasingly atomized, with individuals retreating into private, isolated existences. Or Ray Oldenburg, who wrote in The Great Good Place (1989) about the importance of informal gathering places – cafes, parks, community centres – where people can meet and interact and relax without the pressures of work or family. Or – from the other end of the political spectrum – Roger Scruton, or David Watkin even, or Léon Krier, with his ideas about the “polycentric” city, which makes room for everyone in all types of places and spaces.

I know that the sale of the Central YMCA represents just the latest chapter in a seemingly never-ending story about places being stripped of their social function in favour of the pursuit of personal profit. And I’m not a great campaigner, or an activist – I’m a common reader – but as we lose more spaces like the YMCA, it does make you wonder what kind of a world we’re imagining for ourselves. Mourning the closure of the Central YMCA isn’t just about lamenting the closing of a building, and it’s not about looking back: it’s despair about closing a door to the future. And if you still think that’s just nostalgia, I’d argue that it’s a very particular kind of nostalgia, what C. S. Lewis would call our “lifelong nostalgia”, “our longing to be reunited with something in the universe from which we now feel cut off, to be on the inside of some door which we have always seen from the outside”, which “is no mere neurotic fancy, but the truest index of our real situation”.

Ian Sansom’s books include September 1, 1939: A biography of a poem, 2019

The post You can’t stay at the Y-M-C-A appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:02 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:34:50

1 week ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2025-01-22 14:58:02 | Updated at 2025-01-30 05:34:50

1 week ago