Bernhard Schlink was thinking about moral responsibility and redemption long before The Reader (1997; Der Vorleser, 1995) first appeared. One of Germany’s most distinguished legal academics, he became a judge in 1988 and began to publish fiction at about the same time. His first novels feature a detective called Selb (“Self”), a man haunted by his former complicity with the Nazi regime. The Reader extends Schlink’s reflections on private shame to consider the wider disquiet of a generation struggling with the memory of wartime atrocities. It describes Michael’s adolescent love for Hanna – a woman who had worked as a guard at Auschwitz, as Michael learns long after the end of their affair. Hanna comes to accept her culpability, but is not presented as a monster, and the reasons for her actions are sympathetically explored. “What would you have done?”: Hanna’s challenging question resonates throughout the book.

The international success of The Reader, cemented by a high-profile film adaptation by David Hare, directed by Stephen Daldry (2008), brought both celebrity and censure. Some argued that the novel was an indefensible bid to excuse Hanna, pronouncing on matters where Schlink could have no right to exercise judgement. But the author did not abandon his fictive blueprint. Subsequent novels repeatedly return to the structure of The Reader – featuring a man looking back over his life and pondering its meaning in both personal and national terms, discovering a trail of incomplete documents and oblique clues, reappraising relationships with women who turn out to have secret histories of their own.

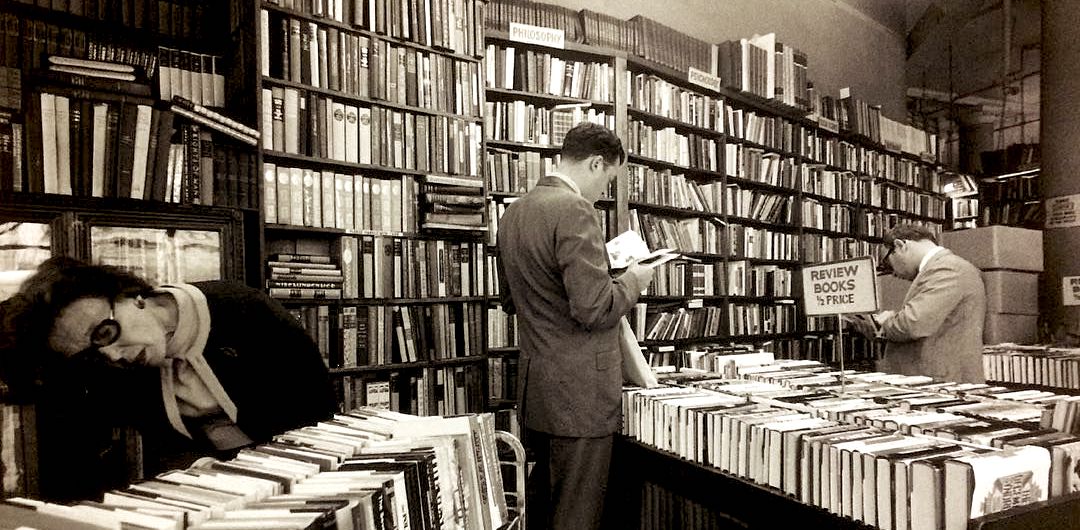

This is also the formula of The Granddaughter (Die Enkelin, 2021), translated by Charlotte Collins, though here Schlink reflects on the reunification of Germany rather than Nazi war crimes. Kaspar is an elderly bookseller in Berlin, mourning the death of Birgit, his alcoholic wife. The couple had met at a GDR propaganda event, the Pentecost Meeting of German Youth of 1964. Birgit had become unreachable in the depression she tried to medicate with wine, but Kaspar’s devotion never faltered, and he now embarks on a quest to understand the pain that eroded her life. Her computer holds the key: he discovers an autobiographical fragment describing her abandonment of a baby daughter conceived before her marriage, left behind as she fled East Germany to join Kaspar in the West. Birgit, it seems, did not regret her choice, but she is typical of Schlink’s protagonists in that she was also unable to escape a corrosive sense of guilt.

Kaspar begins a determined search for Svenja, the lost child. Eventually, and somewhat improbably, he tracks her down in eastern Germany, where she lives with her tyrannical husband, Björn, in a völkisch community deep in the countryside. Escaping miserable years of violence and drug abuse, she has fallen into the comforting certainty of far-right ideologies. Sigrun, her fourteen-year-old daughter, unquestioningly accepts the neo-Nazi doctrines of her parents. It becomes Kaspar’s mission to open Sigrun’s eyes and, persuaded by a hefty bribe, Svenja and Björn allow her to stay with him on a regular basis. Step by step Sigrun moves away from the dogmas of her childhood and rebuilds her future.

The strength of The Granddaughter lies in its exploration of the legacies of a divided Germany and its thoughtful acknowledgement of aspirations that were finally defeated when the Wall came down. Despite the chaos of Birgit’s life, she was fundamentally serious in her response to culture and politics (“If a thing was serious, she took it seriously”), and in this she represented the values of the GDR. Schlink, who is a deeply serious writer, is drawn to the culturally conservative ideals of East Germany’s discredited model of socialism, though he is clear-eyed about the cruelties of its ruling regime. When Birgit studied literature in the West she was frustrated by the desiccated approaches she encountered, wishing instead to allow the text “to touch and change me, to see its power, its beauty, its greatness, to understand and love it”. These are sentiments the novel endorses.

The story is engaging on many levels, but stumbles in its depiction of Sigrun. Her first rebellion against her community leads her to join a violent far-right group; later she develops an aptitude for music and embarks on a career as a classical pianist. At no point is she a credible character. She is a mouthpiece for Bernhard Schlink’s anxieties about the rise of the extreme right and for a searching interpretation of his country’s recent history. But she is not the voice of a new generation in Germany.

Dinah Birch is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Liverpool

The post Allow the text to touch you! appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-27 16:50:21 | Updated at 2024-11-28 02:35:33

10 hours ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-27 16:50:21 | Updated at 2024-11-28 02:35:33

10 hours ago