Thomas Mann’s modernist magnum opus The Magic Mountain, a landmark novel of ideas-cum-comedy of manners set in a Swiss tuberculosis sanatorium, was published on November 28, 1924. On the German literary scene that year, its publication dramatically overshadowed an event that had taken place six months earlier in another TB sanatorium: the death of Franz Kafka. The Jewish writer from Prague died at the age of forty, having earned some renown for a small number of short stories, his three novels left unpublished. The appearance of the 1,000-pageThe Magic Mountain put Mann on an upward trajectory: about to turn fifty, the scion of a bourgeois Hanseatic family was fast becoming the most famous German writer alive. Five years later he would be crowned with the Nobel prize in literature.

Over the past century the fortunes of these two very different masters of the German language have reversed in popular culture and scholarship alike. At the outset of the twenty-first century, David Damrosch compared the fates of the two in an entertaining footnote to his influential study What Is World Literature? – “The MLA Bibliography shows that during the sixties, Mann was more often written about in English (142 items) than Kafka (111 items). They were in a dead heat in the seventies (476 entries for Mann, 478 for Kafka), and then Kafka took a decisive lead in the eighties, rising to 530 while Mann dropped dramatically to 289. Kafka dipped somewhat in the nineties, to 411 items, but still retained a substantial margin over Mann, who had 277”. This trend continues today. In 2024, the death of Kafka has overshadowed the centenary of The Magic Mountain.

But why compare the two writers like this? Can they not simply exist as two separate literary entities, rather than being locked in a competitive struggle for readers and fame? The answer is not really, for they have been read alongside or against each other for more than a century. In 1955, the year of Mann’s death, György Lukács wrote an essay pointedly titled “Franz Kafka or Thomas Mann?”, in which he compared their modernist aesthetics and – counterintuitively for leftist intellectuals today – came out in support of Mann. But the two writers had not seen each other as adversaries. Kafka was enjoying a short story by Mann as early as 1904, at the age of twenty; in 1917, already ill with tuberculosis, he wrote that he “hungers” after Mann’s writing. In 1921, while at work on The Magic Mountain, Mann was introduced to Kafka’s works and found them “remarkable”; a couple of months later he was still reading them “with much interest”. One scholar has postulated that the character of Mynheer Peeperkorn in The Magic Mountain, a Dutch colonialist from Java who revels in lavish meals à la the Last Supper, was intended as a mirror image of Kafka’s hunger artist, the protagonist of a story that Mann probably read as soon as it was published in 1922.

A much more direct influence on Mann’s portrayal of Peeperkorn was Gerhart Hauptmann, the author of naturalist novels and plays such as The Weavers (1892). He was also Mann’s natural literary rival. While not exactly a household name today – though he is still regularly staged in German theatres and taught in German schools – in the early 1920s Hauptmann was the most celebrated German writer alive. Widely regarded as Goethe’s twentieth-century successor, he had been the most recent German winner of the Nobel prize in literature, in 1912, at the age of fifty. Now in his early sixties, he was an unquestionable literary icon, an imposing presence with a characteristic mane of grey hair and a repertoire of memorable mannerisms. Mann, the master of vivid description, made Peeperkorn look and sound just like him.

The striking similarities between Peeperkorn and Hauptmann were not lost on the early readers of The Magic Mountain. Many commented on Mann’s irreverent treatment of his older and more esteemed colleague – including Hauptmann. On January 4, 1925, just over a month after the novel’s publication, he complained in a letter to their mutual publisher, Samuel Fischer: “a Dutchman, a drunkard, a druggist, a suicide, an intellectual ruin, destroyed by a life of vice, tainted by sacks of gold and malaria – Thomas Mann has dressed such a man in my clothes”. He went on to list features of his that Mann had given to Peeperkorn, from the tendency not to finish his sentences (“a bad habit I have on occasion”) to the talon-like fingernails (“almost like devil’s claws”). To add insult to injury, the novel repeatedly makes mention of Peeperkorn’s “Kapitänshand” (‘captain hand’): “one only needs to consider”, the author of the letter commented caustically, “that the German word for captain is ‘Hauptmann’”.

Mann responded with insolent flattery, addressing his missive to “dear great revered Gerhart Hauptmann”. Despite the compositional necessity of the figure of Peeperkorn, he explained, for a long time he had not been able to “see, hear, or possess” him. Then, in the autumn of 1923, he happened to stay in the same hotel as Hauptmann, whose whole being simply “lent itself” to the portrayal. What Mann did not add is that the association of Peeperkorn with Hauptmann offered a delicious opportunity for a series of literary puns playfully establishing the author of The Magic Mountain as the heir to Hauptmann’s mantle. “Hauptmann” is indeed the German term for “captain”, but the literal meaning is “main man”. On meeting Peeperkorn, Hans Castorp – the artless protagonist of the novel – becomes a cipher for his creator. Castorp is “the insignificant young man” (“Mann” in German) to “the great old one”, Peeperkorn. Around page 750, it is finally confirmed (spoiler alert!) that in the narrative gap between the first and the second volumes of the novel, Castorp had slept with Clawdia Chauchat, a Russian woman now accompanied by the Dutch colonialist. Characteristically for Mann, this heterosexual conquest is reported in a moment fraught with homoerotic tension, as Peeperkorn holds Castorp by the wrist and the two “read in each other’s eyes”.

This intertwining of literary rivalry with sexual and imperial politics has become particularly ripe for reassessment today. Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium: A health resort horror story rewrites The Magic Mountain from the perspective of feminist and postcolonial critiques. Published in Polish in 2022 (and just recently in English, in Antonia Lloyd-Jones’s translation, reviewed by Claire Lowdon in the TLS, September 20, 2024), it is her first novel since she won both the International Booker and Nobel prizes in 2018. Elegant and witty, Tokarczuk’s novel pays homage to Mann’s luxuriously descriptive and effortlessly atmospheric style, but displays as much irreverence towards Mann as the latter showed towards Hauptmann.

A particularly questionable part of the sanatorium treatment in The Magic Mountain consists of fortnightly lectures on psychoanalysis given by Dr Krokowski, a suspicious character from eastern Europe. One memorable iteration is on the subject of mushrooms – “these creatures of the shade, luxuriant and anomalous forms of organic life, fleshly by nature”. Dr Krokowski alights on one fungus in particular: Phallus impudicus, or the common stinkhorn, “which in its form was suggestive of love, in its odour of death […] it gave out that odour when the viscous, greenish, spore-bearing fluid dripped from its bell-shaped top”. As in her other novels, in Tokarczuk’s take on The Magic Mountain deviant sexualities come to the fore and mushrooms sprout out of control, becoming a symbolic tool to dissect and deconstruct the casual misogyny that forms the backdrop of Mann’s novel. Her fungi are always associated with central-eastern Europe as well as femininity. To her, both are characterized by boundless fecundity, threatening to stifle the masculine, western European logos.

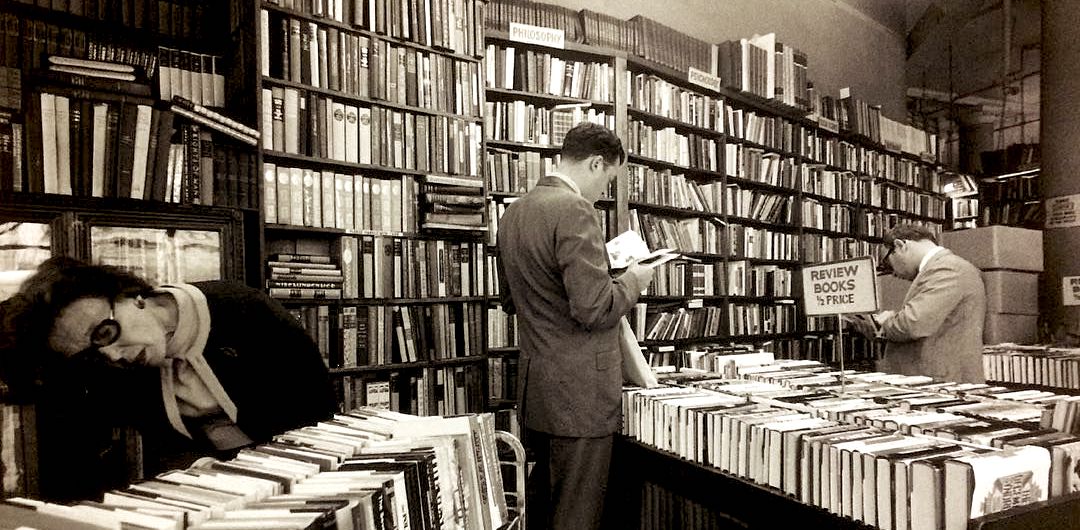

Tokarczuk explicitly compared the central European novel to mycelium in a lecture given in Japan in 2013, in which she defined the region as a postimperial space. Set in 1913, the year Mann began writing The Magic Mountain, The Empusium takes place in a resort town now in Poland, but then under the Prussian partition. As Polish and German patients meet, myths of Germanic cultural superiority and racialized prejudice against Slavs come to the fore. In this context it is fitting that one important function of Tokarczuk’s version of The Magic Mountain is to write herself into the canon of world literature. She made several telling references to Mann in her Nobel acceptance speech, but he had been on her mind for decades. In the 1990s, she published a short story – as yet untranslated – in which an unnamed Polish woman stalks Mann on his book tour in Poland and surreptitiously caresses a copy of The Magic Mountain in a bookshop. Now she has written her own version, mirroring Mann’s project to establish himself as the greatest German writer alive at the expense of Hauptmann.

The centenary of the publication of The Magic Mountain may have been overshadowed by the centenary of Kafka’s death, but the English translation of Tokarczuk’s novel is not the only new publication to mark it. Not one but two new English translations of Mann’s magnum opus are in progress: Susan Bernofsky’s for W. W. Norton and Simon Pare’s for Oxford World’s Classics. Both translators have been reporting on their work on their respective blogs. In Germany, Fischer has released a handsome “deluxe edition” of the novel and Rowohlt another literary rewriting, Heinz Strunk’s pointedly titled Zauberberg 2, while C. H. Beck is preparing a dedicated compendium. A week-long celebration of the original Zauberberg took place in August in Davos, where the novel is set, and another in the autumn in Lübeck, Mann’s birthplace. Centenary events offer a chance to reflect and mark the passage of time, but the real fun lies in seeing who makes the next move as a new century of literary rivalries unfolds.

Karolina Watroba is the author of Mann’s “Magic Mountain”: World literature and closer reading, 2022, and Metamorphoses: In search of Franz Kafka, 2024

The post Mann and the main man appeared first on TLS.

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-27 16:50:20 | Updated at 2024-11-28 00:45:53

8 hours ago

By Times Literary Supplement | Created at 2024-11-27 16:50:20 | Updated at 2024-11-28 00:45:53

8 hours ago