The U.S. Air Force’s new Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) drones are being developed around fundamentally different understandings of maintenance, logistics, and sustainment, with a heavy focus on commercial-of-the-shelf components, than the service’s existing crewed and uncrewed platforms. This is particularly true regarding how CCAs will be supported at forward locations during future conflicts as the drones are the first aircraft designed from the ground up around concepts for distributed and disaggregated operations collectively referred to as Agile Combat Employment (ACE).

The Air & Space Forces Association hosted a panel discussion on CCA logistics at its 2025 Warfare Symposium yesterday, at which TWZ was in attendance. Air Force Maj. Gen. Joseph Kunkel, Director of Force Design, Integration, and Wargaming within the office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Air Force Futures, was one of three panelists. The other two were Mike Atwood, Vice President for Advanced Programs at General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. (GA-ASI), and Andrew Van Timmeren, Senior Director of Autonomous Airpower at Anduril Industries.

In 2024, the Air Force picked GA-ASI and Anduril to design and build CCA prototypes, now designated YFQ-42A and YFQ-44A, respectively, as part of the program’s first phase or Increment 1. Requirements for a second tranche of CCAs, or Increment 2, which could be more costly, are coalescing now. The service expects to buy between 100 and 150 Increment 1 CCAs, but has said in the past that it could ultimately acquire at least a thousand of the drones across all of the program’s increments. It remains unclear whether the Air Force plans to buy just YF-42As or YF-44As, or a mix of both, under Increment 1.

A composite rendering of the CCA designs that General Atomics, at top, and Anduril, at bottom, are currently developing, along with their new formal designations. General Atomics/Anduril

A composite rendering of the CCA designs that General Atomics, at top, and Anduril, at bottom, are currently developing, along with their new formal designations. General Atomics/Anduril “We need to think about how we survive and generate combat power from the inside, and how do we strengthen our position on the inside? And part of that is distributed basing,” Kunkel said near the start of yesterday’s panel discussion by way of introduction. “The ability to create multiple dilemmas for our adversaries, … multiple places where they have to distribute and make choices about whether they’re going to target or not, that’s a really big deal for us.”

“That distributed basing also creates a lot of inefficiencies in how you might sustain something,” Kundel continued. “Some of the design attributes that these two teams have been building into their CCAs are exactly that – you don’t want to have a huge additional footprint that’s required. You don’t want to have, like, the big sustainment requirements.”

“You want to be able to use commercial stuff to the max extent [so] you don’t have to take specialized refueling equipment, specialized loading equipment” to forward locations, the Air Force’s force design boss added.

Specialized maintenance and logistics demands, as well as the need for more bespoke equipment on the ground to support flight operations, have been major hurdles for the Air Force when it comes to implementing the ACE concepts using existing crewed and uncrewed aircraft.

GA-ASI’s Atwood highlighted lessons learned from the Air Force’s Rapid Raptor and Rapid Reaper concepts for quickly deploying small force packages of F-22 Raptor stealth fighters and MQ-9 Reaper drones, respectively, along with supporting assets to forward locations. The MQ-9 is another General Atomics product and the company helped in the development of a ‘kit’ to assist with deploying and sustaining those drones within the ACE construct. This includes using the Reapers themselves to carry their own sustainment kits into a remote locale and to conduct limited resupply missions by carrying small cargoes in travel pods under their wings.

A travel pod under the wing of an MQ-9 Reaper. USAF

A travel pod under the wing of an MQ-9 Reaper. USAF “So our CCA aircraft uses that pedigree” and has “a footprint today” that is focused on forward-deployed operations and reducing maintenance demands as much as possible, Atwood said yesterday. “The best aircraft is the one you don’t do maintenance on.”

He also highlighted “condition-based maintenance” concepts leveraging systems on the drones to alert maintainers and help them start ahead of larger issues. The CCA “should tell you when it’s starting to cough a little bit and get sick.”

General Atomics’ CCA design also incorporates other features to ensure it can operate from more far-flung locations with more limited infrastructure, including shorter and less well-maintained runways. Atwood again used prior experience with the MQ-9 to help illustrate these challenges.

“We showed up at these World War II leftover airfields. And we quickly realized these airfields are in really bad shape, really bad shape, and we started to really appreciate runway distance,” Atwood explained. “It’s hard to make a fast-moving aircraft use a lot less runway. And so what we realized is we needed a trailing-arm landing gear.”

A trailing-arm helps smooth the impact of landing, which in turn can help reduce wear and tear. This is especially beneficial for CCAs flying from short and potentially rough fields during future operations.

A model of General Atomics CCA design. Jamie Hunter

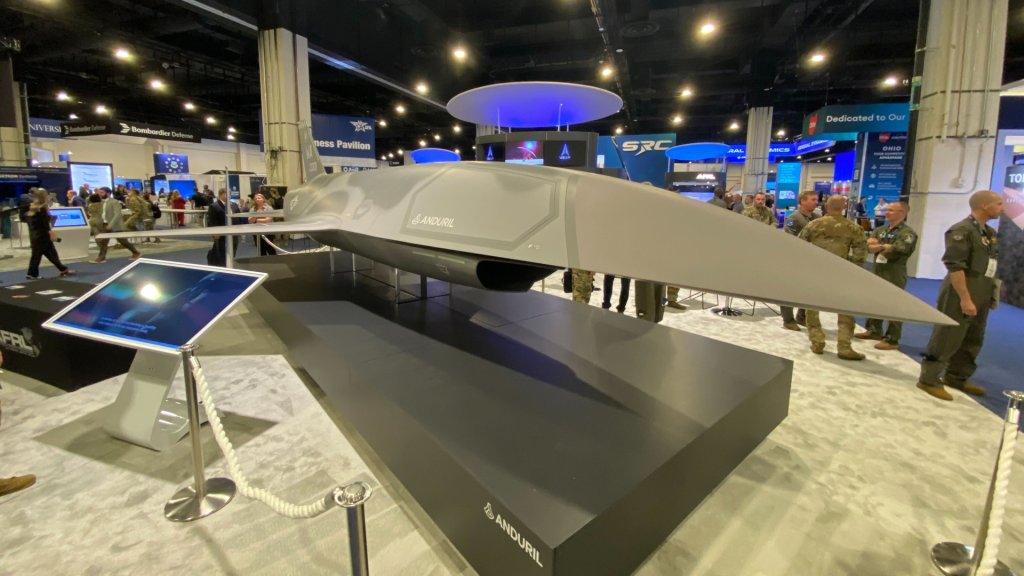

A model of General Atomics CCA design. Jamie Hunter When it comes to Anduril’s CCA design, also known as Fury, Van Timmeren talked about how features to make it more readily maintainable in the field, as well as low-maintenance overall, were baked in early on. Van Timmeren, a retired Air Force officer who flew F-22s, previously worked for Blue Force Technologies, which started Fury’s development in the late 2010s and was then acquired by Anduril in 2023. You can read the full story of how Fury came to be in this past in-depth TWZ feature.

“Early on, you communicate with your engineering team, not just the performance characteristics of the hardware that you want … we also want to say everything has to be easily accessible for the design. Everything has to be easily line replaceable,” Van Timmeren said yesterday. “We have ease of access for all the panels [on Fury].”

Another “one of the things that’s critical to the ease of supportability is leveraging as much as possible commercial components. So engines that are flight-certified, already in mass production for the civilian aviation community. Wheels, tires, brakes, hydraulic actuators, all the sub-components that go into a vehicle,” he added, also noting that no bespoke tools are required to do work on Fury.

A model of Anduril’s Fury. Jamie Hunter

A model of Anduril’s Fury. Jamie Hunter A “perfect example of that actually is the engine [on Fury],” Van Timmeren continued. “We’re using a commercial engine that is in production, is FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] certified, millions of flight hours on it.”

Fury is powered by a single Williams International FJ44-4M turbofan engine. FJ44 variants are in widespread use, especially on business jets, including members of the popular Cessna Citation family.

Van Timmeren also used the example of needing to replace a blown tire to further illustrate the value of using components more readily available on the commercial market. Bespoke tires for military aircraft can be wildly expensive, as TWZ has reported on in the past. They can also be harder to source overall.

If you blow a tire, “you might have to go out in the community to find it,” Van Timmeren said. Using commercial parts available through global logistics networks means you can “go to local FBO and buy it,” he added, referring to fixed-base operator/fixed-based operations contractors who provide general aviation support services at airports.

TWZ has reported in the past about the serious issues the Air Force has already been facing with spare part supply chains, especially when it comes to the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. During yesterday’s panel discussion, both General Atomics’ Atwood and Anduril’s Van Timmeren highlighted the benefits that new and improving manufacturing processes, including 3D printing and other additive manufacturing techniques, are also expected to bring to the CCA sustainment pipeline.

Supporting CCA operations, especially at more remote and/or austere forward locations, isn’t just about the drones themselves. Maj. Gen. Kunkel had already highlighted these issues just recently at a separate talk the Hudson Institute think tank hosted last week.

“I will tell you, some of it’s not like the sexy, cool stuff. It’s like the basics. It’s like bomb loaders, missile loaders, and, you know, refueling trucks and, you know, electric carts and air conditioning carts,” he said at that time. “They’ve got to be made differently.”

To help in this regard, General Atomics’ CCA design features an all-electric start-up capability that requires no off-board support. “So you can hit a button, the plane will start up, taxi, [and] take off all on its own,” according to Atwood.

Any ground support equipment and other assets needed to support CCAs at forward locations also have to be able to get there in the first place with the same level of rapidity.

“I employed the James Bond model. I only want to maintain something that I could jump out of the back of the C-130 with,” Atwood said.

“When you think about the sustainment architectures that we built in the past, the thought was that they were going to be in sanctuary. So, you know, you could afford to build a piece of aircraft ground equipment that weighed 10,000 pounds and wouldn’t fit on a C-130,” Maj. Gen. Kunkel had also noted last week at the Hudson Institute talk.

Members of the U Air Force unload lighting carts from a C-130 at Moscow’s Vnukovo International Airport in support of President Barack Obama’s visit to Russia in 2009. USAF

Members of the U Air Force unload lighting carts from a C-130 at Moscow’s Vnukovo International Airport in support of President Barack Obama’s visit to Russia in 2009. USAF Focusing assets that will fit inside a C-130 or a similarly-sized platform may not be enough to support future CCA operations.

“We use MQ-9 to carry parts between bases, and that’s something we’ve done in the past, and something we’ll continue to do,” but “the concept of logistics, what we need for airlift, is going to change potentially,” Maj. Gen. Kunkel said yesterday. “And you need a cargo aircraft that can very agilely deliver parts, and deliver weapons, and deliver material to places that are inside.”

“I think CCA can actually be, in some cases, a mobility aircraft,” General Atomics Atwood said, highlighting the internal bay on his company’s design. “One of the reasons that GA chose to have an internal weapons bay was for carrying not just missiles and kinetics, but to do that logistics.”

All of this is set to have downstream operational and other impacts across the Air Force.

“So many people think about survivability in the air, in air combat phase, but just as important is survivability on the ground,” General Atomics’ Atwood said. The ACE concepts of operations, at their core, are heavily centered on making it difficult for an opponent to target friendly forces on the ground. There also an increasingly heated debate about whether the Air Force, in particular, should be doing more to physically harden its existing main operating bases against attack, as you can read more about here.

“So, minimizing your turn time on the aircraft,” helped by using commercial components and supporting assets, “gets you to have a turnaround time that is extremely difficult for the adversary” to get its targeting cycle around, Atwood added.

Atwood further noted that the often discussed need for more “affordable mass” to provide the required air combat capacity to win future conflicts could be provided with fewer platforms if they’re more survivable, including on the ground, and can be employed at a very high tempo.

The General Atomics executive also highlighted the value of increasingly autonomous capabilities in further reducing the required footprint on the ground. “The other part about autonomy is it takes a [control] van out of it. So I need less deployed footprint, less chow halls, less barracks,” Atwood said.

The view inside a ground control station for the MQ-9 Reaper. USAF

The view inside a ground control station for the MQ-9 Reaper. USAF “For a number of ways, simplicity eliminates vulnerabilities,” Maj. Gen. Kunkel also said. “What it also does, it opens up the aperture on where you can actually place these things.”

Kunkel noted that CCAs could operate from allied and partner airbases, and even from commercial airports, in addition to fully U.S.-controlled facilities, during future operations.

The Air Force has already been using a mix of test aircraft, crewed and uncrewed, to help lay the ground work for its future CCAs, including just how the drones will be integrated into its force structure and day-to-day training and other activities, as well as combat operations. Yesterday, Kunkel noted that his service has established an Experimental Operations Unit (EOU) dedicated to this work at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. The Air Force announced last year that it would be increasing purchases of prototype Increment 1 CCAs to further help in this regard.

CCAs are “going to be the first aircraft that we have developed specifically for ACE,” Kunkel stressed. “That’s going to be the game changer for us.”

For the Air Force to truly get the most out of its future CCA fleets, a new logistics and sustainment ecosystem will be required. General Atomics and Anduril have already been baking those demands into their YFQ-42A and YFQ-44A designs.

Contact the author: [email protected]

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-06 19:26:01 | Updated at 2025-03-06 22:26:35

3 hours ago

By The War Zone | Created at 2025-03-06 19:26:01 | Updated at 2025-03-06 22:26:35

3 hours ago