In his much-discussed piece on the Los Angeles fires at The Free Press, Leighton Woodhouse looks to Mike Davis for a narrative foundation. In his book Ecology of Fear, Woodhouse notes, Davis “argued that the area between the beach and the Santa Monica Mountains simply never should have been developed. No matter what measures we take to prevent it, those hills are going to burn, and the houses we erect upon them are only so much kindling.” Malibu and the Palisades, the land of hard living. That’s why so many rich and famous people lived there: because it was so inherently miserable and dangerous.

Mike Davis was full of sh-t for 30 years — he died in 2022 — and I’ve been rolling my eyes at him throughout. He described Los Angeles as an “apocalypse theme park,” a place of ruin and pain, populated by hardened survivors who, “dutifully struggling,” stagger on through the “Job-like ordeal” of clinging to a brutal landscape.

Also, Sierra Madre has bears. The Los Angeles suburbs are a place of horror and agony, because they back into the mountains, where blood-clawed wild animals prowl and stalk and slaughter. Places where life is especially grim and sanguinary, pgs. 240-41: Bradbury, La Crescenta, Glendora, the areas around the hellscape of Santa Barbara. A poodle was eaten by a mountain lion in Bradbury once, as neighbors gaped in open-jawed terror, YET STILL DO FOOLS ENDURE THE HORROR OF LIVING IN SUCH A PLACE.

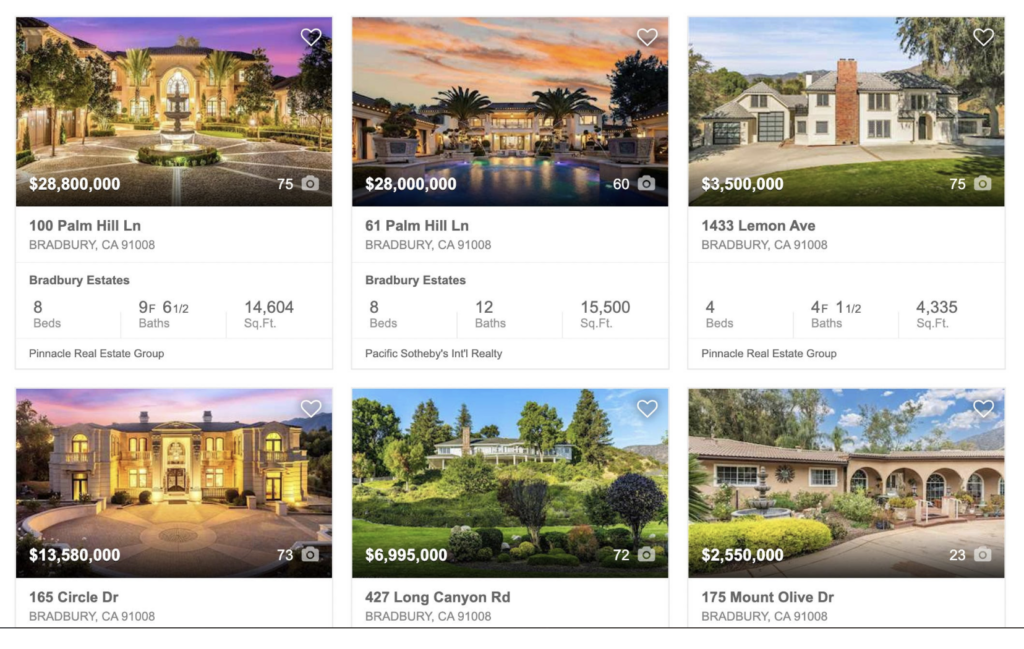

Here are current real estate listings in Bradbury, a gated hillside community incorporated as an independent city in the San Gabriel Valley with a population of about 900 people:

How then would ye endure such horror, oh pilgrim, to live thus amid such blood and death? How bearest thou brutal existence upon this land?

Famously, in 1999, the Los Angeles Times, which used to be a newspaper, ran a long story examining Mike Davis and his vision of Southern California. It’s full of sentences like this:

- “Los Angeles’ most provocative social critic has stretched, bent and broken more than a few facts in ‘Ecology of Fear,’ his latest, darkly themed work on the urban area he claims to love.”

- “…more than a third of the time there were factual problems with his work.”

- “Davis concedes the error.”

- “Davis does not say where he got this piece of information.”

- “‘I honestly don’t know what I’m referring to,’ Davis said.”

- “Some of Davis’ mistakes involve mergers of fact and fiction, including making up a quote.”

- “Davis attributes the false quote to a mix-up.”

- “Then he takes readers on a partial flight of fantasy…”

- “An examination of the Malibu Times article shows that Davis made up the parts about the jewels, the hair color, the kayakers’ occupations, the evidence of their callous classism and the ethnicity of their maids.”

- “Davis is mischievously unrepentant.”

- “Davis also merges fact and literary fiction, without acknowledgment, while arguing that Pomona, like other older, outer suburbs, is dying.”

And so on.

The Times concluded that Davis could be read as “a polemicist, who makes cogent, incisive arguments on big themes,” but not as “a historian who is expected to be reliable, even on details.”

Los Angeles has disasters, yes. It burns, and we have earthquakes. Coyotes will eat your cats. Bears will soak in your hot tub.

But ease is the actual point of the place, an argument Davis advanced while he made up a bunch of dumb sh-t about the agony and the horror. Comfort is our rock. Yes, people start wearing parkas and gloves and wool hats when the temperature plummets into the 50s. The current weather is a bit colder than we’re used to for early January, but we’re enduring.

If you live in Los Angeles for 30 years — about 10,957 days, depending on how many leap years you get in — you’re going to have about 10,950 days that are extremely comfortable and a few days when you’re on the roof with a garden hose, watching the embers, or surfing the shifting foundation of your house as the tectonic plates grind.

My wife had a New York childhood and says that hell no she’s not going to ever again live where it snows; she moved to Los Angeles after college FOR A REASON, thank you very much. We’ve all lived here in this place of absurd comfort that goes wrong every few years because we manage the modest risks — by crazy expedients like having good fire departments and clearing the flammable brush, strategies that left the rails at some undiscussed point.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power recently tried to replace flammable creosote-coated wooden poles for powerlines in the area that’s now burning in the Palisades fire, putting in fire-resistant steel poles in their place, but environmental activists stopped the work.

The Los Angeles Fire Department laid off mechanics to save the city money for social justice programs and so has an enormous portion of its fleet sitting unusable in a city repair yard, untouched. We knew this before the fires:

Los Angeles Fire Department chief Kristin Crowley lists amount of out of service LA Fire Department equipment: – 40 fire engines How could Gavin Newsom and Karen Bass let this happen? pic.twitter.com/fm4bTgMTjz

– 36 rescue ambulances

– 10 of our trucks also out of service

– Close to 15%-20% of our fleet

- Forty fire engines out of service as the city burns;

- Ohhh, the landscape of ruin!

The point to make about the landscape isn’t that it’s inherently likely to burn; the point to make is that we stopped preparing for that likelihood, slipping into the ease of the place on a raft made of luxury beliefs.

I know the places that have burned. I’ve walked and driven the streets that are gone. I’ve watched the burning foundations of a building I used to live in, restaurants we visited, stores we shopped in. My favorite memory of Pacific Palisades, a sort of small town that lived as an island of comfort in a declining city, Mayberry RFD for the well-to-do, was the time I stood behind a middle-aged woman at Noah’s Bagels who was interrogating the staff about each bagel, at great length, as the line spooled out behind her: “Now, tell me about the blueberry bagel….” She wanted a deep dive on ingredients, grams of carbohydrates, grams of protein, sugar content, baking technique. The staff pulled out a binder to consult on the matter. I eventually gave up and looked for breakfast somewhere else on the block. It’s the place where extremely comfortable people pursue what they want, oblivious to surroundings.

This is the kernel Mike Davis got right, and it’s the reason the place has failed. Everywhere burns or shakes or freezes or blows down. The susceptibility to natural disasters isn’t the least bit a distinctive feature of Los Angeles — zero, nada, none, not at all. It’s the universal human condition, mitigated by action. Or not mitigated by action.

The fault isn’t in the land. Don’t look for it there.

This article was originally published on the author’s Substack, “Tell Me How This Ends.”

Chris Bray is a former infantry sergeant in the U.S. Army, and has a history PhD from the University of California Los Angeles. He is the author of "Court-Martial: How Military Justice Has Shaped America from the Revolution to 9/11 and Beyond," published last year by W.W. Norton.

By The Federalist (Politics) | Created at 2025-01-15 12:47:04 | Updated at 2025-01-15 15:58:15

3 hours ago

By The Federalist (Politics) | Created at 2025-01-15 12:47:04 | Updated at 2025-01-15 15:58:15

3 hours ago