Uncategorized

Pete Hegseth should focus on shifting the American defense burden elsewhere, not on sharing it or changing course to meet it.

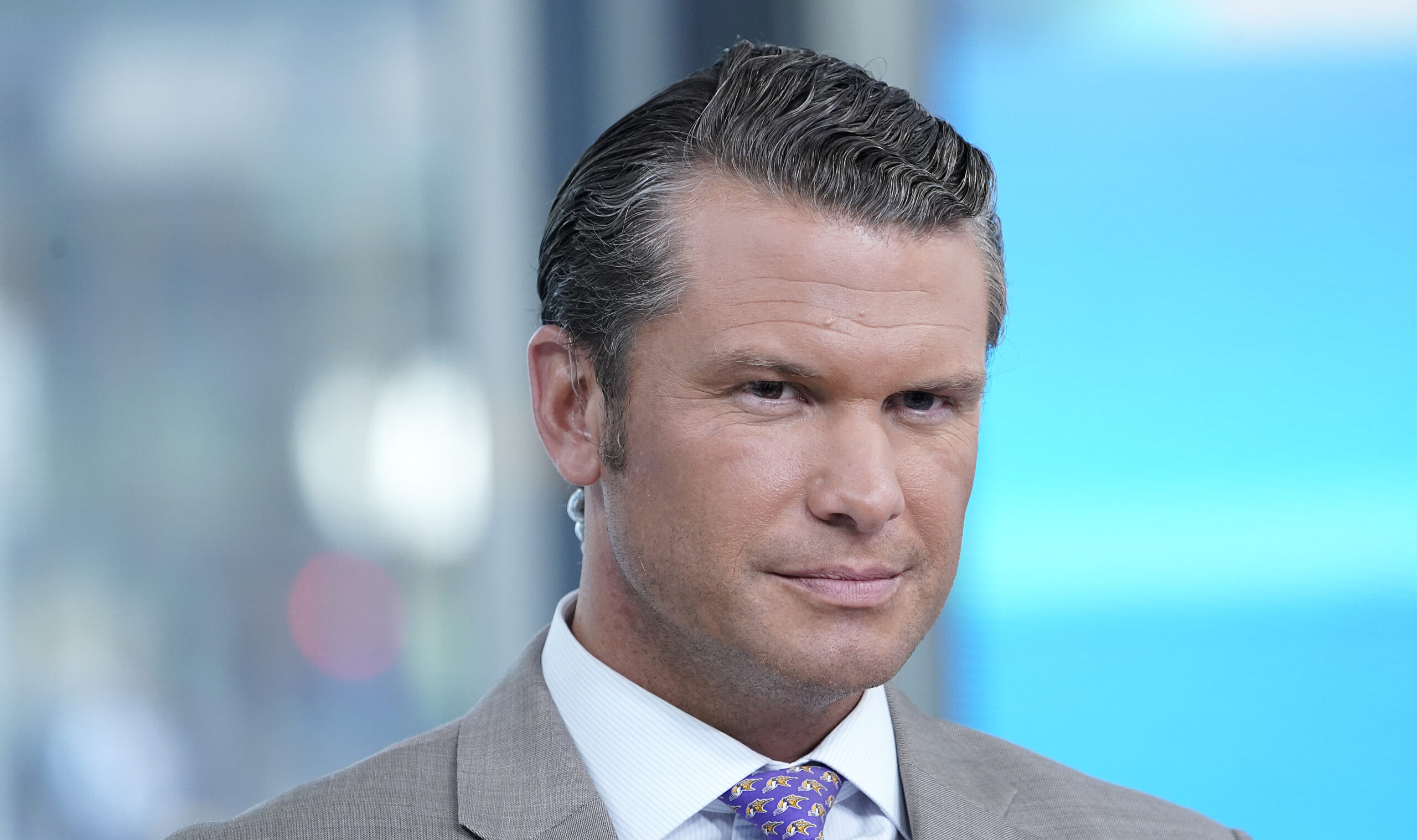

Donald Trump’s nominee to run the Department of Defense, Pete Hegseth, appears likely to win Senate approval, albeit by a small margin. With few of the traditional qualifications for the job, his backers hope he will shake up a Pentagon used to losing wars that the U.S. should not have fought.

Yet he believes the military’s recruiting crisis–which eased some last year but is by no means solved–is a problem of insufficient personnel. He told the Senate Armed Services Committee, “I think that the decline in end strength since 2021 is due to recruiting challenges rather than a conclusion that our military needed fewer forces. This has occurred during an era of increasing security challenges. Therefore, it is likely that the military’s current end strength is insufficient to accomplish its mission.”

Nevertheless, despite promising he would be different from his predecessors, he too is taking American foreign policy for granted. In practice, Washington’s denizens want to do everything, having expanded the venerable Monroe Doctrine to demand that other governments accept not only American intervention throughout the Western Hemisphere, but around the world. The result has been constant foreign meddling and, all too often, full-scale wars.

The U.S. began as a weak commercial republic amid multiple globe-spanning empires. Three of the latter, Great Britain, France, and Spain, clashed on the North American continent. Thus, a policy of domestic expansion and foreign restraint made sense. When retiring from public life, George Washington famously inveighed against overseas entanglements. He explained, “Nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others, should be excluded; and that, in place of them, just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated.”

That only changed toward the end of the 19th century when the U.S. first engaged in “saltwater imperialism,” brutally seizing the Philippines from Spain after claiming to go to war to save the Cuban people. Washington then deployed Madrid’s murderous tactics in Cuba against Filipino civilians, killing a couple hundred thousand of them.

Even worse was the military manifestation of Woodrow Wilson’s megalomania, American intervention in the First World War. The nominal justification for America’s entry into the grotesque slugfest among imperial European powers was to vindicate the right of American civilians to book passage on belligerent passenger liners which were designated as reserve warships and carried munitions through a warzone. The outcome was an unbalanced peace settlement which loosed communism, fascism, and Nazism upon Europe and ultimately the world. Then came the horrors of the Second World War and the near misses of the Cold War.

When the latter ended the U.S. could have returned to an earlier, more peaceful foreign policy. After all, the U.S. enjoys essentially splendid isolation, completely dominating its own hemisphere, bounded by vast oceans east and west and weak, pacific neighbors north and south. The only existential threat could come via missiles, and American retaliation would ensure the annihilation of any aggressor.

Yet the U.S. continues to patrol the globe, defending prosperous and populous allies, battling terrorists and insurgents spawned by its own policies, underwriting regime change, variously promoting stability or democracy, and often meddling just because it can. America’s bizarrely inconsistent and often ruthlessly stupid foreign policy is feasible only because the U.S. military is far larger than that necessary for defense. In short, if you want to micromanage a usually recalcitrant and often hostile world, you need force structure, including a lot of manpower.

How to convince young women and especially men to sign up for military duty when it evidently has nothing much to do with defending America? Instead, new recruits will get to spend their time, and potentially lives, remaking the likes of Afghanistan and Iraq. Or protect wealthy industrialized “allies” in Europe which can’t be bothered to defend themselves. Or be tasked with whatever other bizarre duties the likes of Joe Biden or Donald Trump, or, even worse, George W. Bush or Woodrow Wilson, might concoct.

Although disastrous misadventures such as the Iraq War have been the costliest in recent years, potential nuclear cataclysms involving major adversaries, most notably Russia and China, are the most dangerous and unnecessary. Why, eight decades after the conclusion of the Second World War, are the Europeans still desperately dependent upon America? And why, after three years of war in Ukraine, are the Europeans making so little progress in turning their militaries into serious forces capable of defending their nations?

Consider Germany, which possesses the continent’s largest economy and has demonstrated extraordinary martial ability in its past. Despite a much-celebrated and supposedly path-breaking Zeitenwende made shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Berlin’s military efforts have been disappointing. According to Stars and Stripes, a publication aimed at U.S. service members and their families:

Germany is rearming too slowly to counter Russia and will need as long as a century to build up parts of its military inventory to the level of 20 years ago, according to a think tank report released Monday. The analysis by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy says Germany is barely managing to replace the weapons it is sending to help Ukraine’s war effort—stocks of air defense systems and howitzers have plummeted, for example—and is not spending enough to stand up to Russia.

Since World War II the United Kingdom has maintained the most capable European armed services. Moreover, it has been the most hawkish of the western European states regarding the need to confront Russia and ensure Ukraine’s victory over Moscow. However, the Brits apparently still expect the Yanks to make this happen. When the UK’s then-Defense Secretary Ben Wallace announced plans to shrink the army, he insisted his nation didn’t need a big army since it was on an island.

This policy continues. In October, reported the London Independent: “Defense Secretary John Healey has shocked MPs after he admitted that the army is on course to fall to its lowest number of personnel for more than 230 years. Answering questions from in parliament, the minister confirmed that the size of the army will fall below 70,000 for the first time since 1793.” And this isn’t likely to change. The Labor Party government elected last summer is assessing the UK’s military requirements, but “the size of the British military is not expected to increase under the strategic defense review despite warnings by chiefs that the world is more dangerous than it has been in decades.”

Yet Hegseth, along with the rest of official Washington, believes that America’s defense problem is failing to create a large enough military, and especially an army. Even as Uncle Sam runs annual deficits approaching $2 trillion and spends more than $1 trillion on interest a year. And as the US has run its national debt up to 100 percent of GDP and is on its way to nearly twice that high by mid-century.

As secretary, Hegseth should push burden-shifting, not burden-sharing. The job of the American armed forces is to defend the U.S., not run the world. Washington’s responsibility certainly is not to protect rich friends forever, enabling them to concentrate on investing in their economies and meeting their people’s social needs. And nothing will change until the U.S. starts doing less for Europe.

Nearly 14 years ago, then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates issued a prescient warning in his valedictory policy speech:

The blunt reality is that there will be dwindling appetite and patience in the U.S. Congress—and in the American body politic writ large—to expend increasingly precious funds on behalf of nations that are apparently unwilling to devote the necessary resources or make the necessary changes to be serious and capable partners in their own defense. Nations apparently willing and eager for American taxpayers to assume the growing security burden left by reductions in European defense budgets.

Indeed, if current trends in the decline of European defense capabilities are not halted and reversed, future U.S. political leaders—those for whom the Cold War was not the formative experience that it was for me—may not consider the return on America’s investment in NATO worth the cost.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

That world has arrived.

Trump's first term highlighted his antagonism toward European governments, which he believed were little better than defense leeches. Yet his own appointees undercut his position by continuing to treat the Pentagon as a welfare agency for wealthy friends. In contrast, Hegseth should take the lead in helping the president redirect US defense policy and force structure back to its primary role, protecting the American people—their lives, territory, liberties, prosperity, and constitutional republic.

Trump wants to make America great again. In truth, the U.S. never stopped being great. However, the denizens of Washington at times did seem dedicated to changing that. The most important way to preserve America’s unique status and mission today is to follow the sort of “humble foreign policy” proposed but almost immediately abandoned by President George W. Bush. In such an effort, presumptive Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth will have a vital role to play.

By The American Conservative (World News) | Created at 2025-01-23 05:05:08 | Updated at 2025-01-23 09:37:41

4 hours ago

By The American Conservative (World News) | Created at 2025-01-23 05:05:08 | Updated at 2025-01-23 09:37:41

4 hours ago